A Tale of Two Lenders

The Peril of Lenders of Second to Last Resort

It was not until the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in the spring of 2023 that all but the most astute financial literati had heard of the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) System, let alone spent much time thinking about it. A relative backwater of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), the group has quietly provided hefty line items on the liability side of bank balance sheets large and small, ostensibly in order to support affordable housing. Thousands of miles away, in São Paulo, Brazil, the Credit Guarantee Fund (known commonly by its Portuguese acronym, the FGC), acts as a private(ish) consortium of banks providing deposit insurance for the Brazilian financial system. Largely out of the political limelight, these two organizations have shared one defining characteristic: they have acted as de facto lenders of second-to-last resort (LOSTLR), providing emergency and semi-emergency funding to financial institutions, allowing borrowers to avoid going to the central bank. This setup—not unique to these two countries but well exemplified by them—is suboptimal and harmful to the lender of last resort (LOLR) capacities of the central bank.

Central Banks as LOLRs: Birthright?

Walter Bagehot—economist, central banking maestro, onetime editor of The Economist, and namesake of the Yale Program on Financial Stability’s New Bagehot Project—had a doctrine about lending in a crisis, then applicable to the Bank of England when he wrote it in 1873:

“A panic, in a word, is a species of neuralgia, and according to the rules of science you must not starve it. The holders of the cash reserve must be ready not only to keep it for their own liabilities, but to advance it most freely for the liabilities of others. They must lend to merchants, to minor bankers, to ‘this man and that man,’ whenever the security is good.”

Volumes more, of course, can be said about this, but for our purposes what is particularly important here is that Bagehot’s dictum applies to central banks (i.e., monetary authorities), not fiscal authorities, private banks, deposit insurers, or your uncle’s trust fund. To be sure, non-monetary authorities have, indeed, done emergency lending (not always well), and that is precisely our subject of interest.

Taking the naïve view, it may be unclear why exactly it ought to be the central bank doing the lending. Lending, even in crises, [1] has existed without central banks. After all, fiscal authorities (ministries of finance, treasuries) can and do lend money, even to sovereigns, all the time. Indeed, some central bank lending tools like currency swap lines have fiscal authority counterparts. Further, as the branch of government (generally) specializing in the realm of non-monetary-policy financial and economic policies, fiscal authorities should be adequately equipped and funded to handle emergencies in the markets they regulate. Finally, in most governments recognizable to constitutional liberal democrats (note the small “l” and small “d”), fiscal authorities are a part of government more directly accountable to its relevant demos than central banks, so may be seen as the more legitimate and therefore appropriate body to be putting taxpayer money on the line. More simplistically, fiscal authority specification aside, theoretically anyone with enough money ought to be able to lend, whether or not in a context of urgency, to anyone else, assuming they have enough capital and technical capability—and this happens, take for example short-term emergency lending in the form of bank deposits in the spring of 2023 from a consortium of private banks to the failing First Republic Bank.

For five reasons, though, emergency lending ought to be done by central banks.

1. Most fundamentally is the unique ability of a central bank (in a fiat money system) to create money—i.e., reserve creation. While it may sound like an alarmingly unlikely scenario to advanced-economy readers, the reality is that in crises, many fiscal authorities themselves simply run out of money and raising more of it would be prohibitively expensive because of sharply rising risk premia (or secularly higher rates that could have led to the crisis in the first place). Central banks can create reserves—yes, “print money,” if you insist [2]—and that is a vital crisis-fighting tool. Importantly, this means they don’t have to raise debt funding in order to make a loan, which is otherwise a serious constraint, particularly during market stresses.

2. As a practical matter, central banks have bank supervisory staff—actual people whose full-time jobs it is to supervise banks—who have uniquely relevant information regarding the financial health (e.g., solvency, viability) of banks.

3. Central banks have macroprudential authority—i.e., it is in their mission statement to care about financial (in)stability—and therefore they are countercyclical lenders (though this could fairly be said about any government body with a macroprudential mandate and money to lend). This also ties into political optics: central banks are meant to be lending to troubled banks in a crisis, whereas others might (understandably) face more criticism for exposing themselves to unnecessary counterparty risk.

4. Also related to the reserve-creation bit, central banks have some operational advantages. Because they can immediately create reserves and are in the business of doing so, and are further in the business of evaluating collateral during times of systemic headwinds, they can pretty quickly get a loan out the door. As an operational (and deceivingly prosaic) matter, they can and often do operate later in the day than normal debt markets, which limit other potential lenders.

5. In a deeply integrated global financial system, funding pressures may be foreign currency-denominated in some countries or, in the US context, foreign banks may have emergency liquidity demands that only the central bank can meet for legal and operational reasons.

In sum, while a troubled bank could go to many non-central bank places for emergency funding, you probably don’t want them to, because central banks are just best equipped to do their job.

But that doesn’t mean they won’t.

Data from Des Moines: The FHLBs and Systemic Risk

Again, much could be said here about the FHLBs, and won’t be, because it’s been said well elsewhere. Our aim is to paint in broad strokes how the FHLB System interacts with the Fed. First, a little context. The FHLB System was created in 1932 to plug a gap in emergency funding available to housing lenders. FHLBs are federally chartered cooperative financial institutions, which means that while the system is federally chartered, each FHLB is in fact privately owned by its own members (i.e., it is capitalized by them) and, as a result, only FHLB members can obtain FHLB services. The FHLB system’s mission has changed over time, primarily through the Savings and Loans Crisis, and today the FHLBs provide liquidity to member institutions in the form of secured loans called advances. FHLBs fund this lending by issuing joint and several liabilities (i.e., liabilities issued at the system level), which enjoy relatively low yields from an implicit government guarantee (FHLB debt is considered a Federal Agency security). Notably, a financial institution need not be primarily engaged in housing lending to borrow from an FHLB—today the FHLBs lend to commercial banks of all stripes in the country.

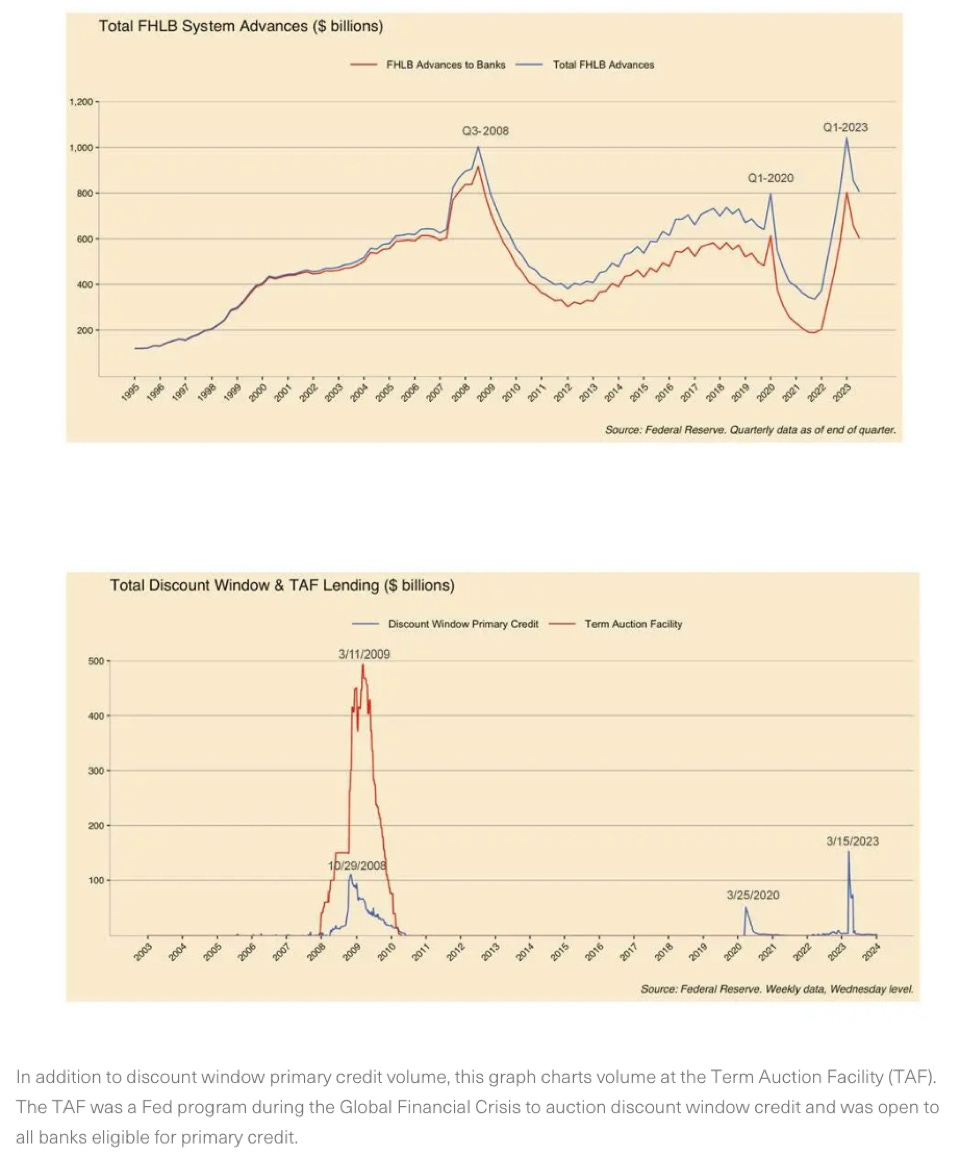

More to our interest, though, the FHLBs also do a fair bit of emergency-lite lending, acting as a de facto LOSTLR. In fact, during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), from July 2007 until February 2008, the FHLBs did more lending than the Fed (!) and until September of 2008 still did at least half:

Source: Ashcraft et al.

In explaining this dynamic, Fed researchers pointed to two drivers, which will come up again: discount window stigma (stigma resulting from borrowing from the Fed’s discount window since borrowers’ identities are—with a multi-year lag—eventually released) and the relative cheapness of FHLB advances. But this LOSTLR lending wasn’t limited to the GFC:

Source: FHFA

And, for those who were plugged into the Spring 2023 banking drama, you’ll recall that the FHLBs lent heavily to the very banks that failed:

Source: FHFA

Not to state the obvious here, but that lending was not all successful. In the case of SVB, it made a request to the San Francisco FHLB for a $20 billion loan (against $20 billion of collateral SVB had prepositioned at the SF FHLB). But that request came too late in the day because, remember, the FHLBs have to raise funding on debt markets and they simply didn’t have enough time before those markets closed. SVB tried to have the SF FHLB move its collateral to the Fed, but procedurally, the SF FHLB needed to keep some collateral for loans outstanding to SVB and needed to move the remaining collateral (once it figured out how much that was) through the Bank of New York Mellon (BONY) to the Fed. The Fed’s wires closed at 7pm EST—that’s 4pm PT—which wasn’t enough time. The next day, the transfer from BONY went through, but as FHLB and SVB managers awaited a call from the Fed, an announcement from the FDIC came through: they’d be shutting down SVB and taking it into liquidation.

So, obviously this was not ideal. Ideally, SVB would’ve had collateral pre-positioned at the Fed’s discount window and would have gone to the Fed first, and early. (And the Fed would’ve kept its wires open later.) In a twist of irony almost too good to be true, we have an ex post article entitled “FHLBs Are in Vogue” calling FHLBs the “lender of first resort” from Silicon Valley Bank. Here’s SVB on the FHLBs (my emphasis):

“It is a common form of financing for most depository institutions with no stigma attached to those who borrow from the FHLB . . . Banks can turn to the FHLB to attract funding to guard against potential liquidity crunches . . . [In March] clearly there was some stress in the system.”

Yeah, clearly.

Discount window stigma is a well-studied thing we won’t go deeply into, but the long story short is that banks are stigmatized from borrowing from the discount window (1) in part because it might (two years later, but still [3]) mark them as a weak institution to the market and (2) in part as a result of mixed messaging from the Fed itself. The lack of similar stigma associated with FHLB borrowing results partly from extremely limited disclosure from the FHLBs on their borrowers. But there’s a second piece at play here: the FHLBs’ less-than-clear lending policies result in lending rates that are often below the Fed’s emergency lending rates, driving more stigma toward the discount window and more emergency-ish (certainly stress-period) borrowing to the regional FHLBs. My brilliant colleagues at the Yale Program on Financial Stability have done an excellent piece on this (data work by yours truly). In a nutshell: when a bank borrows from an FHLB, they are required to buy some “activity-based” stock, which usually works out to be 4–5% of the total loan value. That stock then pays (relatively) high dividends, offsetting the interest the borrower pays to the FHLB. That “dividend rebate” encourages more borrowing (note the dividend stock could be based on affordable housing goals, but is not) and often drives the adjusted rate below the Fed’s primary credit (discount window) rate. This isn’t top secret; the FHLBs explain it, it’s just that not many folks are looking.

Sources: YPFS

And to be sure, it works: FHLBs lend a lot more than the Fed does, even and especially during market stresses.

Source: YPFS

The issues here aren’t lost on anyone. Here’s Ashcraft et al. from the Fed; YPFS (Kelly, McLaughlin, and Metrick) here and here; Kathryn Judge from Columbia Law; Cecchetti, Schoenholtz, and White at Money and Banking; Robin Wigglesworth at FT Alphaville; and Baer, Nelson, Parkinson and Waxman at the Bank Policy Institute, to name just a few. Recently, though, even the FHLBs’ regulator, the FHFA, has taken notice and says it’s aiming for reform itself (FHFA report, pp, 31–32, my emphasis):

“Ensuring that the FHLBanks are not acting as lenders of last resort for institutions in weakened financial condition will allow the FHLBanks to use their available liquidity to provide financing to all members . . . During the 2023 market stress caused by multiple regional bank failures, it became apparent that several large depository members were effectively using the FHLBanks as their lender of last resort. These members did not have agreements in place or collateral positioned to borrow from the Federal Reserve discount window. Accordingly, FHFA will provide guidance to the FHLBanks to work with their members and the members’ primary federal regulators to ensure all large depository members have established protocols to borrow from the Federal Reserve discount window so that these institutions’ borrowing needs continue to be met. Additionally, FHFA expects the FHLBanks to negotiate appropriate agreements with the regional Federal Reserve Banks to ensure expedited movement of collateral if a member’s lending activity must be moved to the Federal Reserve discount window.”

Okay, so, the good people in academia and government have figured out this kink in the system, so, assuming the ability to do some regulatory reform in a fraught political environment (*nervous laughter*), we might be getting somewhere in the US. But the US is not the only place with the LOSTLR problem.

Brazil Does It Too (Differently)

In 2015, a large Brazilian commercial bank—BTG Pactual—faced a liquidity crisis and obtained a large emergency advance. However, the provider of that emergency liquidity was not the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB, the Brazilian central bank), but rather the parastatal deposit insurance organization. Much like the FHLBs, the FGC (again, that’s the Brazilian deposit insurance organization, like America’s FDIC) is privately funded and, ostensibly at least, junior to the BCB in the provision of emergency liquidity. Yet, the FGC has an even more outsized role in the provision of Bagehot-style lending in Brazil than the FHLBs do in the US.

First, the Brazilian system is a little different and merits some at least perfunctory overview. Brazil has an inter-ministerial (American translation: inter-agency) council called the National Monetary Council (known by its Portuguese acronym, CMN), which is composed of the governor of the BCB, the Minister of Finance, and the Minister of Planning and Budget and is tasked with creating monetary and credit policies, maintaining monetary stability, and promoting development. The CMN legally authorized the creation of the FGC, which is itself a private non-profit association. According to the CMN, the FGC “does not exercise any public function” but its purpose is to “protect depositors and investors . . . contribute to maintaining the stability of the national financial system . . . [and to] contribute to the prevention of systemic banking crises” (which sound like a lot of public functions?) (CMN resolution, ch. 1). While the FGC is privately funded, governance changes must be approved by the BCB and submitted to the CMN (CMN resolution, art. 22). So, hence “parastatal.” Prior to 2013, the FGC had no legal authority to lend to its member institutions, but new regulations changed that and, in the process, de facto moved the emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) responsibility from the BCB to the FGC.

With respect to BTG Pactual, the FGC made a sizable (secured) [4] loan and it all worked out fine (the bank was bleeding short-term funding after its CEO was arrested, but he was later acquitted). However, it’s important to revisit the Bagehot dictum about the LOLR not losing money: “No advances indeed need be made by which the Bank [of England] will ultimately lose.” Now, smart people can and do disagree about whether we should be focused on solvency or viability. [5] Regardless, pretty much everyone agrees that you ought to think about one of those things—lending haphazardly to anyone is probably not sound policy. To be clear, I’m not saying that’s what the FGC did (and in fact, folks from the FGC told me that’s very much not what they did), but the IMF said that the FGC’s decision to provide liquidity to BTG Pactual was done with inadequate information about BTG’s medium-term viability.

More generally, the IMF doesn’t like the FGC’s role as a LOSTLR. Here’s the IMF in 2018 (from its 2018 FSAP, pp. 26, 46; my emphasis):

“The role of the lender-of-last resort function has been performed by the FGC in recent times. While this approach has functioned so far, it poses challenges and sets the wrong incentives. It raises the concern that confidential information could leak to the market. Moreover, the private sector may be unwilling or not able to contribute to resolving liquidity problems in large or systemic institutions. Maintaining this system, therefore, could undermine the functioning of the safety net. The FGC is not equipped to analyze appropriately and monitor its clients and does not have a perspective on the viability of banks . . . Returning the ELA function to the BCB should be a high priority. The possible distortion caused by leaving that function in the private sector could undermine the strength of the banking system . . .

The FGC’s provision of open bank assistance is a quasi-central bank function but without central bank safeguards . . . this private sector arrangement could distort the financial sector by supporting weak institutions without corresponding restructuring plans, delaying resolution and prolonging asset deterioration. The simple provision of liquidity without a solvency test or assessment of medium-term viability misses an important safeguard of such lending and should be ruled out, replaced by properly designed ELA from the central bank, with adequate safeguards. Moving the FGC into the public sector would prevent conflicts of interest, help improve the exchange of confidential information, and allow the FGC to be included in high-level crisis management committees.”

Now, to be fair, on the communication/supervisory information bit, the BCB was involved in communication and consultation on the BTG loan specifically and I’m told by FGC staff that the two organizations work hand-in-glove on ELA provision, so perhaps the IMF wasn’t giving them due credit. And things have improved on that front anyways. In its 2023 Article IV Review, the IMF said that the FGC and BCB had made substantial improvements in their coordination (red markup mine):

Note however that Brazil did not “transform [the] FGC into a fully owned public institution.” So, now we know that the BCB will help the FGC not lend to an insolvent/non-viable institution, but that’s no guarantee that it doesn’t. The risk of loss to the FGC—while presumably low (more on that later)—would be much worse than a similar loss to the BCB; in other words, this is sort of a black swan event. If someone’s going to take a loss, it should be the BCB, not the FGC.

To see why, let’s consider an FGC loss. Arguably, that event would be pro-cyclical because the FGC could, like the FDIC, end up levying a special assessment on its members (i.e., every financial institution in Brazil). The FGC could raise money in the debt markets but assuming it just took a loss, that debt would probably be expensive if it could get it at all. Eventually, those higher debt-servicing costs to the FGC would find their way back to FGC membership (i.e., through the income statement to the balance sheet). Either way, reductively, one way to think about this is that if the FGC takes a loss during a systemic crisis, that loss hurts doubly badly because it feeds back to the rest of the financial system in the form of FGC weakness or direct fees on financial firms. This is more directly materially impactful for the financial system than, say, the central bank taking a loss and therefore remitting fewer proceeds to the fiscal authority (since the fiscal authority isn’t owned by members of the financial system).

And while I wouldn’t purport to know how likely an FGC loss is, [6] it’s also worth noting that the IMF pointed out in its 2018 FSAP (p. 45) that the FGC did not have a committed liquidity facility at the BCB and that its funding position was “precarious.” Cf. FHLBs.

Note also the concern about a “systemic institution.” LOLRs throughout history (most recently the Swiss National Bank re: Credit Suisse, but also see Ireland and Iceland during the GFC) have had to provide huge amounts of liquidity relative the size of the national economy. Here the FGC would face the same challenge as the FHLBs: because it can’t create reserves, it would have to raise funding in the market, and the good ole nine-to-five debt market almost certainly wouldn’t support mega-debt, especially in a situation in which headlines are full of hand-wringing about the eminent collapse of [insert household-name bank].

But those weren’t the only concerns the IMF had. Recall the point about conflicts of interest and wearing the central bank’s clothes without having its (protective) authorities. This points to yet another foundational weakness of LOSTLRs: a true LOLR (central bank) doesn’t operate in a vacuum and sometimes emergency liquidity is (1) not what is needed; or (2) not all that is needed. In the height of the global financial crisis, if Citibank had gone to an American version of the FGC and asked for a loan, it would’ve probably gotten one because it had collateral. But as Geithner et al. knew at the time, discount window liquidity was not really what it needed; Citi needed capital. In other words, the LOLR is a constituent part of a wholistic financial stability landscape that includes others, like capital-providers of last resort (fiscal authorities), deposit insurers, and resolution authorities. To have a single (non-prudential) mandate to provide ELA without thinking about all those other things is like a pharmacist playing doctor.

Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Lenders?

Many folks—including some I’ve had the pleasure of working with—analogize responding to a financial crisis to firefighting. When a fire breaks out, you (sensibly) call the fire department. If there were some local brigade of volunteers closer to your home, though, and calling them first caused less alarm, was less likely to get you in the town paper, resulted in generally quicker response times due to proximity, and they made you fill out less paperwork after the incident, might you call them first? Normatively, would it be “bad” that they exist, to the extent that they impede the putting out of fires?

I guess, to take the first question, you might call them first if you just started a fire in your trashcan, and that’s probably fine. In fact, it might be better, because you’ve kept the real fire engines in service, freeing up the cavalry to respond to bigger, more serious fires. This is a sort of helpful division of labor and, so long as the local volunteer brigade is capable of putting out small fires, this is maybe a good equilibrium. If, however, your house is burning down and calling the local brigade first results in a delay for the fire department’s arrival, this is a (big) net loss. Worse, their trucks and personnel in your driveway might actively impede the fire department. More abstractly, if you reach for the local brigade first, always, because of some fear of social stigma from your neighbors if you call the fire department when you don’t really need them, we might all suffer some collective action mess where no one actually calls the fire department (!). This is plainly bad.

LOSTLRs are, I think, the same. It’s no great harm to have a second string so long as it in no way impedes the actions of, or discourages the use of, the first string. In our examples, the FHLBs and the FGC clearly are in need of a rethink in terms of how they exist in the financial stability space and how they interact with LOLRs. That doesn’t mean they can’t play a constructive role, but it means that they aren’t doing so in their current forms (at least so far as emergency lending in concerned—they have vital other functions!).

So, why and how have the LOSTLRs stuck around? Clearly, lots of smart folks (cited throughout) writing from places like Columbia, Yale, the IMF, and the Financial Times are aware of the problems. In my view, a large part of the story is discount window stigma. The IMF in 2018 was onto this when reviewing the FGC operations (my emphasis):

“This shift of a quasi-form of ELA to a privately-owned FGC reflects several factors including . . . the preference of the banks to borrow from the industry in order to avoid the reputational issues connected with borrowing funds from BCB.”

If your discount window is stigmatized, the existence of a LOSTLR only exacerbates that stigma. For policymakers, that’s a problem. For banks, that’s an advantage. Until the discount window is destigmatized, there will be strong demand from banks for a LOSTLR: they’ll still need liquidity, but they want to get it from somewhere that won’t mark them with a scarlet letter.

At their worst, LOSTLRs are a significant and dangerous impediment to safe and sound emergency lending and ergo financial stability. At their best, they can manage to not harm LOLR functions. Emergency lending is one place where pluralism is not better: best to stick to the central banks.

(Disclaimer: This work is independent from and not endorsed by the Yale Program on Financial Stability or Yale University; all views are my own.)

[1] For example, in the US the New York Clearing House Association—a private association of New York banks—served as the LOLR in the Crisis of 1893 and later in the Panic of 1907. Notably, though, this didn’t last and eventually was replaced by the Federal Reserve System.

[2] We need to derail here for a minute to clarify something, which probably deserves an entirely separate monograph (by someone better equipped than I): central banks “printing money” to make an emergency loan is not the same as “pulling money out of thin air.” The reason is that when people say “pulling money out of thin air,” they use the word “money” to mean “wealth” or “value,” when it really is a subcategory of wealth or value lying on the more liquid end of the liquidity scale. When a central bank creates reserves for Borrower Bank A, it creates a liability item on its balance sheet, but it then has an equal and opposite line item on the asset side of its balance sheet for the value of the loan to be repaid, secured by collateral. In other words, the central bank did not just magically snap its fingers and create newfound economic value (wealth) out of nothing; it merely transformed a non-liquid asset (a claim on the bank, and as last resort a claim on its assets posted as collateral) into a more liquid asset. Indeed, liquidity transformation is a pretty good definition of exactly what the process of money-creating is (which is, incidentally, the whole business of banking).

[3] Additionally, the market can often piece together (or at least speculative on) a weekly basis which banks might have done the borrowing since the Fed’s weekly data is broken down by district region.

[4] To be sure, the FGC did demand significant collateral (with a haircut) and obtained personal guarantees—yes, personal—from BTG Pactual’s largest shareholders.

[5] This is more than a semantic debate. A firm could be insolvent at a particular time (i.e., they have negative real equity), but could be perfectly viable as soon as the run stops (like BTG Pactual) and therefore insolvent but viable. Alternatively, a bank could be solvent at a particular time but not viable because their business model is moribund (Credit Suisse, 2023).

[6] Spend enough time doing financial crisis research, though, and you’ll see that the realistic potential of losses for emergency lenders generally (and I’m speaking mostly of central banks!) is perennial.