Dispatch No. 5

A roundup of learnings

Legal stuff: I do not do affiliate link programs. Any links to items for purchase here do not result in any commission and/or remuneration of any kind to me. I just like for my readers to be able to buy things they might like (e.g., books).

Dutch Treat: The Netherlands’ Exorbitant Privilege in the Eighteenth Century. Stein Berre and Asani Sarkar. Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Exorbitant privilege is a polarizing concept these days. For those not in the field, it’s basically the idea that the country that provides the world’s reserve currency can finance itself more cheaply than it otherwise would, and that it has an unnaturally high debt capacity due to the large demand for its debt. It pretty much refers to the dollar (the actual quote is from Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, then the French minister of finance, in the 1960s in reference to the dollar’s growing role). But the US isn’t the only country that’s held the exorbitant privilege! The UK did before, but before that, so did the Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries.

I love financial history, in part because it’s just interesting, but in part because it reveals the structural consistency over time—not all that much changes. From the note:

The role of the Dutch guilder as the global reserve currency allowed the Netherlands to have the lowest prevailing rate of interest in Europe, as foreign investors were more willing to exchange their surpluses for financial assets in the Netherlands. One consequence was that foreign investors left large deposits with the leading merchant banks of Amsterdam. Since these deposits paid no interest, they provided these firms with a source of low-cost funding.

This was basically foreign institutional investors placing deposits with the New York Fed prior to interest on reserve balances! Plus ça change.

2034: A Novel of the Next World War. Elliot Ackerman and Admiral James Stavridis, USN. Penguin Random House.

I don’t typically include fiction here, but this novel is likely of interest to Discursive readers. Its description from publisher site is below:

On March 12, 2034, US Navy Commodore Sarah Hunt is on the bridge of her flagship, the guided missile destroyer USS John Paul Jones, conducting a routine freedom of navigation patrol in the South China Sea when her ship detects an unflagged trawler in clear distress, smoke billowing from its bridge. On that same day, US Marine aviator Major Chris “Wedge” Mitchell is flying an F35E Lightning over the Strait of Hormuz, testing a new stealth technology as he flirts with Iranian airspace. By the end of that day, Wedge will be an Iranian prisoner, and Sarah Hunt’s destroyer will lie at the bottom of the sea, sunk by the Chinese Navy. Iran and China have clearly coordinated their moves, which involve the use of powerful new forms of cyber weaponry that render US ships and planes defenseless. In a single day, America’s faith in its military’s strategic pre-eminence is in tatters. A new, terrifying era is at hand.

So begins a disturbingly plausible work of speculative fiction, co-authored by an award-winning novelist and decorated Marine veteran and the former commander of NATO, a legendary admiral who has spent much of his career strategically outmaneuvering America’s most tenacious adversaries. Written with a powerful blend of geopolitical sophistication and human empathy, 2034 takes us inside the minds of a global cast of characters–Americans, Chinese, Iranians, Russians, Indians–as a series of arrogant miscalculations on all sides leads the world into an intensifying international storm. In the end, China and the United States will have paid a staggering cost, one that forever alters the global balance of power.

Everything in 2034 is an imaginative extrapolation from present-day facts on the ground combined with the authors’ years working at the highest and most classified levels of national security. Sometimes it takes a brilliant work of fiction to illuminate the most dire of warnings: 2034 is all too close at hand, and this cautionary tale presents the reader a dark yet possible future that we must do all we can to avoid.

On the scale of tragedy to comedy, this is 100% in the former bucket. 2034 is indeed chilling, not only for its ‘disturbingly plausible’ war scenarios in particular, but for its reminder of the dangers of excesses of human ego and, in the aggregate, of national spirit. If the book sounds far-fetched, an interview with one of the authors (Adm. Stavridis) is worth listening to, as he mentions that Pearl Harbor and the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand also seemed unimaginable at the time. That, he says, is why we have fiction: to avoid the mistake of failures of imagination. If you want some IR-flavored tragedy in your life (or just to think about how scary modern weapons are, or a conflict in the South China Sea or Taiwan might be), this is a must-read. (Incidentally, co-author Elliot Ackerman is currently a senior fellow at the Yale Jackson School of Global Affairs, my current outpost, though I didn’t know that when I was gifted this novel—small world indeed!)

International Lending in War and Peace. Sebastian Horn, Carmen Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch. Riksbank draft paper.

Debt is a surprisingly opaque thing. Private global lending is huge, and also widely known (at least today), but even it suffers from patchy data. Much more opaque then is public lending, i.e., lending from sovereigns and multilaterals. Horn, Reinhart, and Trebesch put together the first consolidated dataset of official capital flows—mostly lending but also aid/grants—from 1790–2020. They offer six primary takeaways:

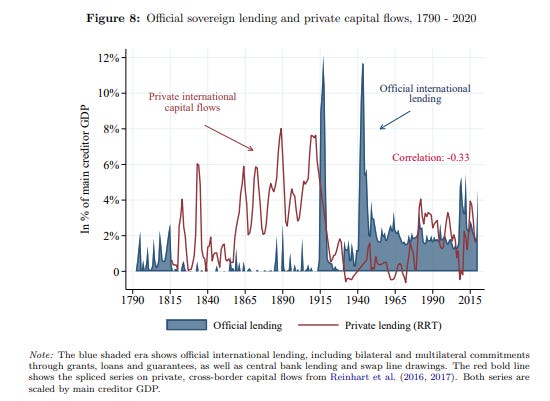

Official lending is actually huge, often eclipsing private capital flows globally.

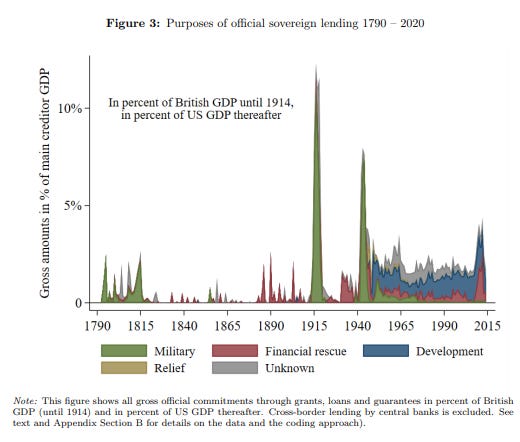

The main driver of official capital flows is war.

In peacetime, the main driver is financial crises (which happen a lot, actually).

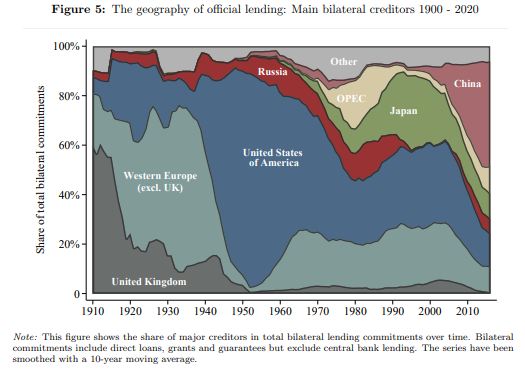

Geopolitical hegemons tend to be the largest official creditors during their respective peaks.

Official capital flows are counter-cyclical: they expand the most when private capital flows dry out.

In war or peace, geopolitics and realpolitik are at play, with nations lending to wartime allies and/or major economic partners.

Theirs is a deeply timely study, highlighting two issues we talk about a lot on this site: the rise of China in the global financial system and central bank swap lines. Here’s a great excerpt (my emphasis):

Our paper helps to better understand the profound changes in the current international financial system. It is not widely appreciated that we are seeing a comeback of state control in international financial flows. China’s rise as an international creditor has been underestimated due to a lack of transparency. We document how China has become one of the most important official creditors worldwide, as almost all of its foreign lending is extended by the government and its state-owned banks (see also Horn et al., 2021). Unknown to the broader public, China has also granted billions in rescue lending to developing countries (Horn et al., 2024). China’s extensive use of state finance is emblematic for other new global creditor powers, such as Russia, India, Brazil or the Arab oil states, who are all prone to use state institutions when allocating capital abroad and who have now all become active official lenders to varying degrees. These new creditors are also increasingly prone to create new multilateral lending institutions, including the Beijing-based Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank or the BRICS Development Bank. “South-South” (official) lending is likely to continue to rise – with considerable state involvement. We are also witnessing a resurgence of official financing via central banks. Central bank “swap lines” have grown in volume and relevance, most evident during the crisis of 2008 and the Covid-19 pandemic. We show that this development is reminiscent of the flourishing cross-border central bank lending during the gold standard era.

Their work is particularly useful for its long aperture, avoiding the recency bias we so often succumb to (my emphasis):

The main advantage of studying capital flows across 200 years is that it allows us to look beyond the current, post-1970 era of open capital accounts, US (dollar) dominance, and relative peace. Our data show that in periods of geopolitical turmoil and great power rivalry, private capital flows can come to an almost complete halt, while state-led finance becomes the dominant form of cross-border capital allocation. This long-run view informs our understanding of what may lie ahead for the global financial system . . . .

It’s hard to overstate the comparative size of official capital flows per this data. The authors report that in major upheavals (e.g., WWI, WWII), official capital flows reached 10% of US GDP. And these data actually understate the “real” official flows, since these data only include official bilateral data, thus excluding sovereign wealth fund investments, which in recent decades have been massive.

Another equally interesting finding is their application of the workhorse gravity model (gravity models never get old!). They find, empirically, that trade exposure, geographic proximity, military alliance, and status of being a former colony are highly predictive of sovereign lender-borrower links, all else equal. This is perhaps not directionally surprising, but very cool to see validated empirically. For example, they find that military allies receive a 100% higher bilateral official flow volume than non-allies (although the predictive strength of military alliances has declined over time).

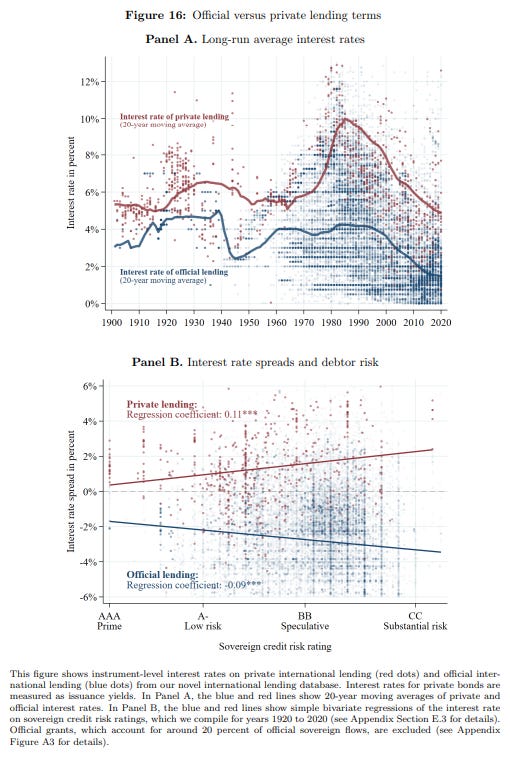

I could sum up more, but a picture says a thousand words, so here are some awesome figures from the paper:

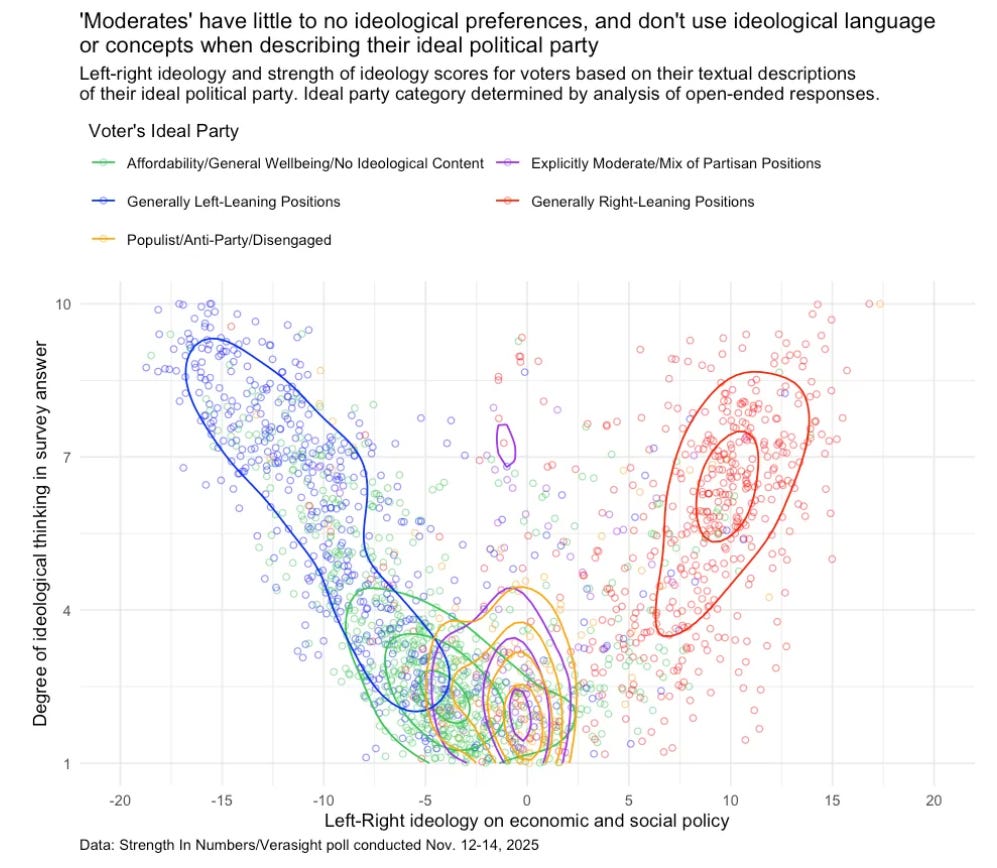

The hidden axis: the left-right spectrum has a non-ideology problem. G. Elliot Morris. Strength in Numbers.

One of my pet interests is political science, in which I would not call myself an expert, but an interested traveler. This excellent essay deserves particular attention. For those who need reminding: the United States does not run ranked-choice multi-member districts with proportional representation. The United States is decided not a parliamentary democracy. The rules of the game in large part dictate the possible universe of outcomes, and in a single-member district first-past-the-post system, we’ll get two parties, more or less. That is not politics; that’s math/game theory. But Americans aren’t so different from other people, so this particular system is reductive to political ideologies. G. Elliott Morris goes to the data to find out what those (considerably more diverse!) political ideologies are. This matters for relatively obvious reasons. In short, per Morris:

What if, instead of making all these assumptions [re survey question design], we simply asked voters straight-up what they wanted their party to advocate for — in their own words? This would certainly get us closer to the result we are trying to draw inferences about.

To this end, in our November Strength In Numbers/Verasight poll I asked over 2,000 Americans to describe, in their own words, their ideal political party. This article analyzes those answers and presents several conclusions for general readers, party reformers, and partisans looking for actual data to guide future electoral strategy.

(For those who have survey methodology questions, please email Morris, I don’t want to talk about two-stage clustering with probability proportional to size and LLMs here. Pls. But yes, N = 2,000 is enough.)

There are some very important takeaways that were not immediately obvious to me, particularly in our hyper-partisan world (where we also often suffer from selection bias in online media). Here are the main three:

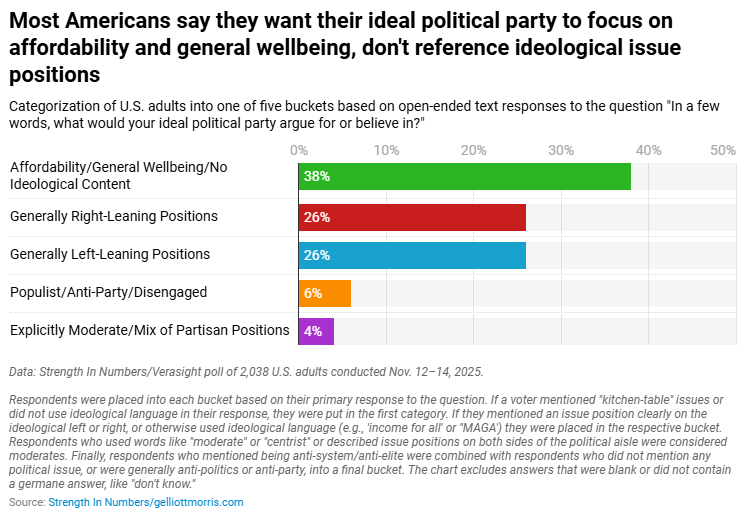

Many Americans—a plurality (38%)—are not ideological at all but are simply focused on quality-of-life issues.

This is kind of surprising! Note that the non-ideological group isn’t “moderate” or “centrist” on the left-right scale (that’s the purple group); they just don’t really espouse partisan views on much at all. In Morris’ words:

The vast majority of respondents in this group also don’t use clearly political language at all . . . In that sense, this group is best described as focused on material wellbeing, and not intensely interested in politics — or potentially even aware of the ideological lines of American politics.

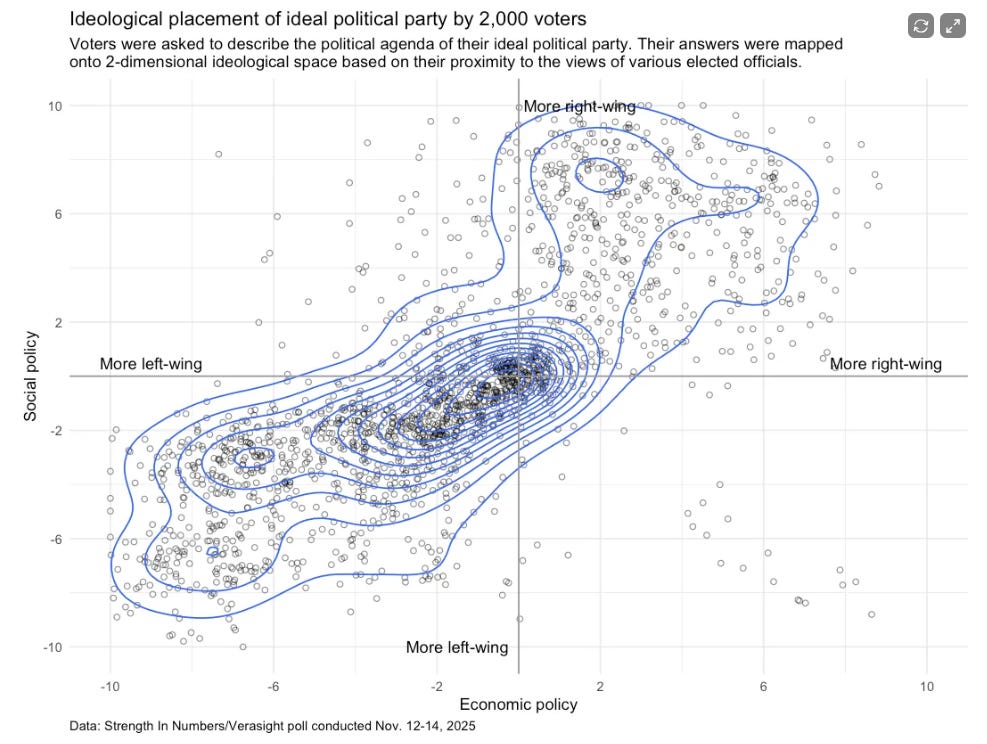

American voters are mostly revealed-preference left-leaning (but only slightly) on both economic and social policy.

This one I found perhaps less surprising than some. Per Pew Research, Americans are basically 49% Democrat or Democrat-leaning and 43% Republican or Republican-leaning. This surprises many Americans, but it’s been true for awhile. (It’s probably surprising because of the institutional rules in America, of which the Senate and electoral college historically overweight rural areas and thus make America look moderately more right-leaning than it is in a population-weighted sense.) However, we shouldn’t overstate the magnitude: the revealed preferences are left, but barely. Most Americans are clustered very near the center, ever so slightly to the left:

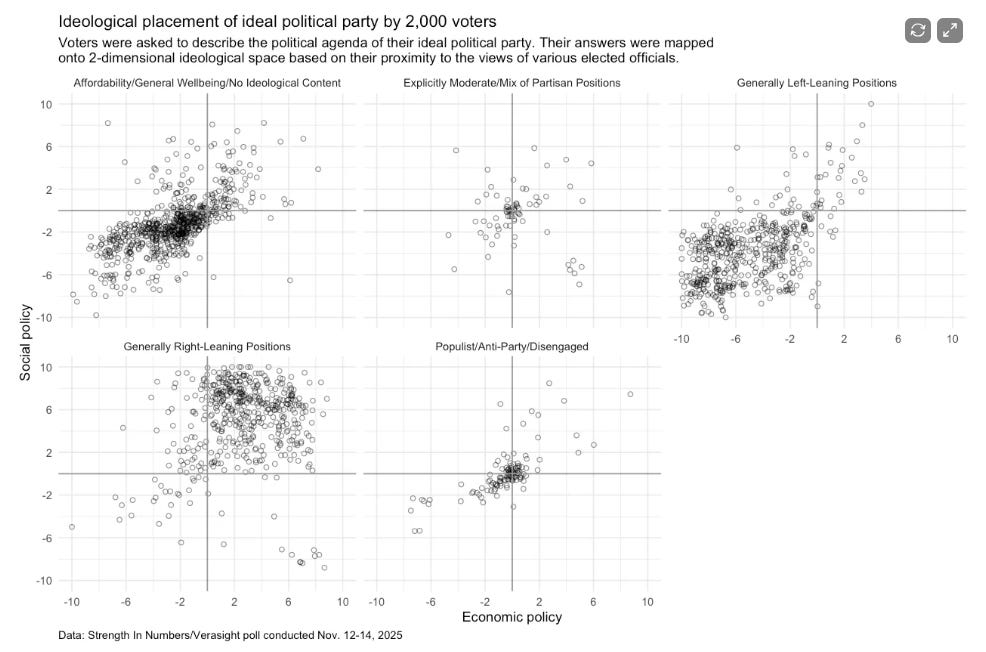

This space clustered around the center is also the home of many independents. Another interesting finding is that if you bin the “non-ideology” group by their revealed policy preferences, they are pretty much that paragon of the average American—pretty centrist, a little to the left (but more on social policy than economic policy):

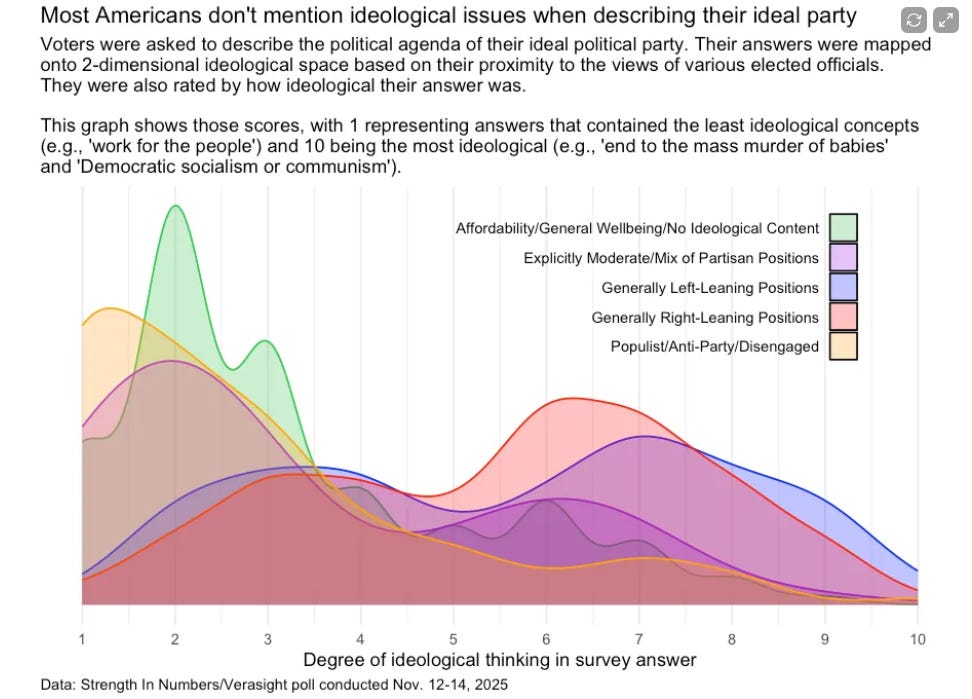

But really, most Americans don’t think very ideologically when they describe an “ideal political party.”

Note the bimodal distribution(s) here, interesting. Probably because roughly four of ten Americans don’t care that much and just want to buy a house.

Those who were grouped into the “left- or right-leaning” camp were in the 6–7 range of ideological intensity, whereas the non-ideology folks were around 2 (the direction of which is no surprise, the magnitude of which did surprise at least me).

To folks who have at least observed American political science from the sidelines, this these findings are perhaps not entirely shocking, but for most of us, this research is probably a healthy corrective for how we think about the American voter.

Morris’s prediction: both parties should battle to win the non-ideology camp by toning down the ideology. As someone who has long been an ideology-skeptic (of all varieties, not just political), that sounds good to me!

For those interested in this literature, I’d also check out research by Lee Drutman, who got his PhD from UC Berkley studying political science. He’s been beating this drum for some time (and, to boot, is associated with both left- and right-leaning orgs, New America and the Federalist Society). If you don’t know what ranked-choice voting or multi-member districts are and are curious, check out FairVote’s explainer (which has a pro-reform bias, to be very clear, but is eminently digestible and has good external links). This is a sadly under-studied area, but it’s super interesting if you like game-theory-lite stuff (or elections).