Is China's Official Lending a Net Positive for the World?

On China’s lending and global welfare

There is an excellent literature about official Chinese overseas development lending. I was asked, in an academic context, to think about the net degree of benefit or cost to global welfare of this lending. That question itself made me reflexively uncomfortable—the economist in me objected to such a question about preferences—but alas, I am a policy person as mentioned, and so naturally have to think about such a normative policy question. This is my attempt at answering that question.

China as overseas official development lender

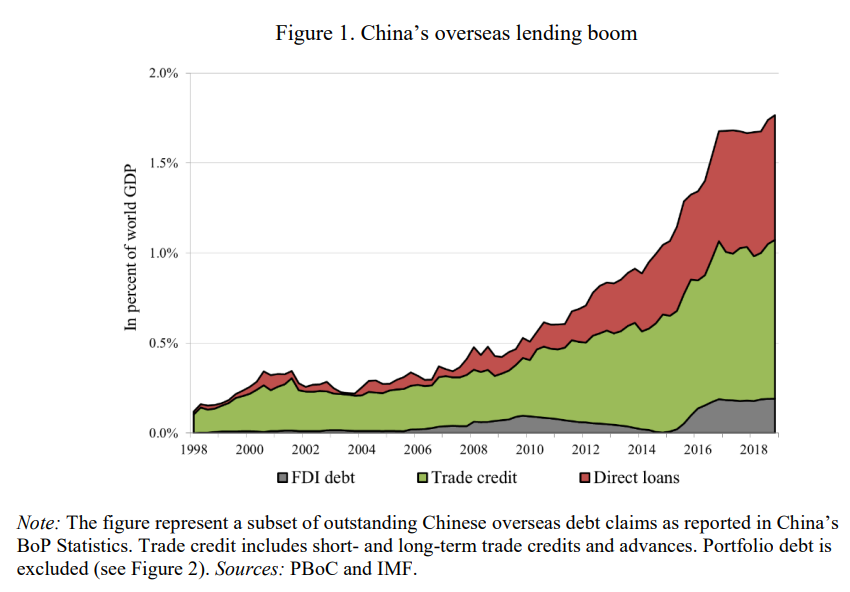

China has long been an international lender, from nearly the founding of the modern People’s Republic in 1949 to today, when Chinese international lending has encompassed the globe, financing dazzling infrastructure projects in the Global South. Chinese overseas lending is, unusually, almost all official, that is, from the Chinese government or its constituent organs. At its 2016 peak, Chinese bilateral lending eclipsed that of all Western creditors combined. While China’s overseas lending crested almost a decade ago, its nominal lending footprint remains massive, and this exposure begs the question: has China’s overseas development lending been a net positive for global welfare?

Chinese lending, 1998–2019

Horn et al. 2019 (6)

Defining Chinese overseas development lending

Sovereign lending is defined as lending by a sovereign, which includes both the state itself, its constituent organs (including state-owned enterprises, SOEs), and parastatals. Usually, sovereign lending (also known as official lending) is to other sovereigns, but sometimes also to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or even corporates. China’s overseas development lending is almost exclusively sovereign.

Chinese sovereign lending can be categorized broadly into four types:

Official development lending (e.g., Chinese policy banks)

Other official lending (e.g., sovereign wealth funds, SOEs, often in the form of commodity prepayment facilities and state-owned commercial bank loans)

Central bank lending (e.g., People’s Bank of China [PBOC] swap lines and deposit loans1)

Indirect lending via multilaterals (e.g., International Monetary Fund [IMF])

I focus here on development lending. This excludes reserve-management “lending” (i.e., China’s holdings of American Treasury bonds or European sovereign debt for purposes of managing its reserves). That is an equally interesting question, but demands a separate analytical framework and differs, both in motivation and mechanics, significantly from sovereign lending practices. I also exclude discussion here of China’s role in the IMF, also an interesting question, but far from the centerpiece of Chinese development lending (for numerous reasons).

Defining global welfare

The net welfare gain (loss) of Chinese sovereign lending hinges on the answers to the following three questions:

Does the lending sustainably support growth and resilience while safeguarding debtor sovereignty to a reasonable extent without creating substantial political distortions?

Could the debtor country have obtained the same quantity of financing on equal or better terms from another lender?

Do the lending practices materially prevent other lenders from being able to participate, in other words, does it systemically complement or systemically hamper the existing network of other lenders and crisis-managers?

A few caveats and clarifications are in order. First, the bar is not so high that there can be no political distortions or limitations on debtor sovereignty—that would be impractical and even at times not preferable. It would also not be comparable with outside options, all of which come with some of that baggage. Second, more is not necessarily better: simply having more financing is not sufficient to be considered a net improvement to global welfare (e.g., the lending could be used to line pockets of cronies, not supporting growth at all while indebting the citizens of the borrower country without their consent). Finally, even if the lending satisfies the other conditions, if it makes borrowing from other sources more difficult, then the bar is much higher for the Chinese lending.

The importance of benchmarking: the counterfactual lender

Doing marginally good lending is necessary but insufficient: if that marginally good Chinese lending displaces even better lending from an alternative lender, that is a net negative for global welfare. Similarly, harmful lending practices are not sufficient to make Chinese lending a net welfare negative: if they are not worse than alternative lending practices, then the marginal effect is zero. Chinese sovereign lending then must be benchmarked against an alternative.2 So, the question must be, ‘is Chinese sovereign lending less sustainable, less growth-supportive, more geopolitically weaponized, etc. than the next-best alternative?’

Does Chinese sovereign lending support growth and resilience?

Numerous academic studies have shown that Chinese lending, inter alia, supports economic growth; supports educational improvement and child health; promotes growth in remote areas; improves poverty alleviation; and helps under-resourced countries meet their infrastructure needs. In this sense, the literature is clear that in nominal terms, Chinese overseas lending has been a boon to growth and development, particularly in the Global South, where it’s most needed.

Of course, the same could be said of traditional multilateral lending, so the question is how Chinese lending supports growth and resilience relative to the next best option. In this sense, uniquely Chinese “circular lending,”3 while perhaps a creative way to avoid graft, raises questions about if more inclusive growth would be supported if the funds actually left the Chinese financial system (e.g., supporting businesses in borrower countries). Similarly, it’s difficult to disentangle Chinese official overseas lending practices from the projects they finance, since the two typically go hand in hand (see aforementioned “circular lending”). In the Chinese lending framework, the norm is “tied procurement” as a part of the package deal, which essentially means the absence of a competitive bid for the project and potentially inflated costs. As researchers at the Center for Global Development point out, “financing terms alone may understate the degree to which borrowers are incurring higher costs relative to what they would have incurred if they selected a more competitive source of debt financing.”

This is all to say that, while Chinese lending supports much-needed growth-positive projects, what is less clear is whether that same growth dividend could be obtained via cheaper and more competitive financing.

Is Chinese sovereign lending sustainable?

Loan characteristics

China’s overseas loans are known to be at considerably higher interest rates and with stricter collateral/balance sheet protection terms than similar loans from alternative lenders such as the OECD and Paris Club lenders. According to scholars at the Lowy Institute (emphasis added):

For the poorest and most vulnerable countries, payments to China make up a quarter of all debt service costs, outweighing both multilateral lenders and private creditors. No single bilateral creditor has been responsible for such a large share of developing country debt service in the past 50 years. In 54 of 120 developing countries with available data, debt service payments to China now exceed the combined payments owed to the Paris Club — a bloc that includes all major Western bilateral lenders.

China’s lending pattern in the past two decades has proven pro-cyclical, as new lending dried up just when it was needed most, with the Paris Club providing countercyclical financing to bridge the gap. It is also true that China’s overseas lending portfolio has deteriorated significantly and divergently from benchmarks. For example, the share of Chinese loan claims on borrowers in distress has skyrocketed in recent years and borrowers with Chinese debt were downgraded by five notches, compared to two notches in a benchmark emerging market index.4

The primary avenue through which Chinese overseas official lending contributes to unsustainable borrowing practices is its non-concessionary nature. Researchers at the Center for Global Development analyzed Chinese and World Bank lending in 157 countries and compared the loan terms. This comparison is particularly useful since the World Bank and Chinese official overseas lending tend to finance the same types of projects (e.g., infrastructure). They found that World Bank financing was considerably cheaper for the borrower and contained larger amounts of grant funding, with a measure of total portfolio concessionality for the World Bank of 42.2% compared to China’s 21.5%. They found that on all metrics—maturity, grace period, and interest rate—World Bank lending was far more debtor-friendly.

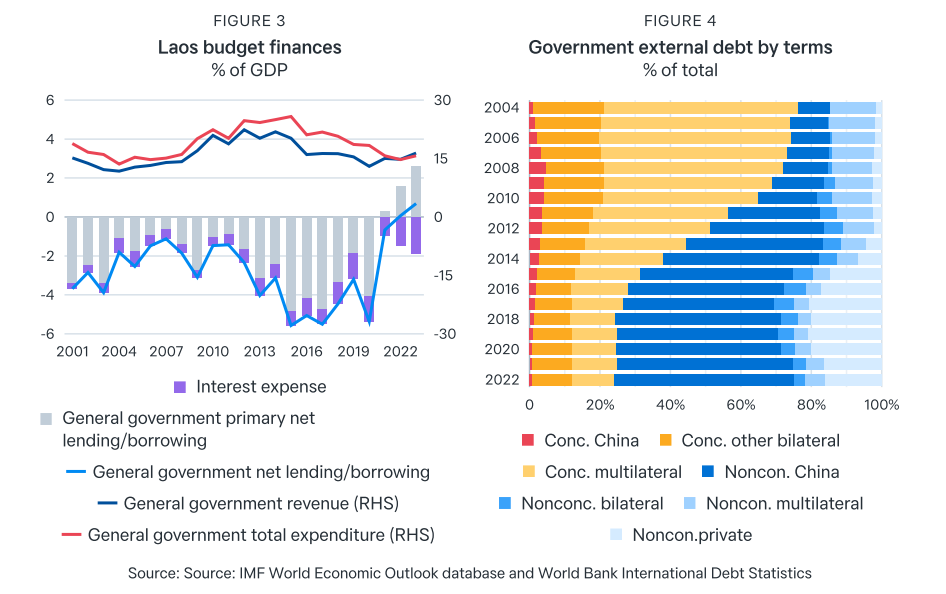

Scholars from the Lowy Institute provide an illustrative example in the case of Laos (emphasis added, references omitted):

Heavy borrowing from China and commercial sources delivered a remarkable reversal in the structure of Laos’ public debt. In 2004, three-quarters of debt was on highly concessional terms and only one-quarter non-concessional. By 2019, that ratio had flipped. Higher interest rates, shorter repayment periods, and the expiry of grace periods on large Chinese loans produced a dramatic rise in debt servicing costs. Including amounts ultimately deferred by China, scheduled debt service payments increased over three-fold . . ..

Laotian debt load with respect to Chinese lenders

Notably, though, even in the case of Laos, China did provide considerable deferral of debt payments and extended a PBOC swap line, which scholars credited with attenuating the impact of Laos’ kip crisis. There is also evidence that borrowing from China has helped debtor countries’ resilience in the face of macroeconomic shocks. For example, Zhengyang Jiang shows that major China-debtor countries tend to experience less exchange rate depreciation and equity market decline in the face of US monetary policy tightening compared to those that borrow less from China. Other research suggests that borrowing from China is associated with muted severity of capital flight during US monetary policy tightening periods, which scholars have termed the “buffering effect” of Chinese lending.

Restructuring

China’s presence in large, complex debt restructurings has made those restructurings more complex, in part because China has been unusually reluctant to grant relief and in part because of the complexity of China’s fragmented lenders. For example, in the case of Congo-Brazzaville in 2018–19, China did not provide financing assurances required to unlock IMF funding, which resulted in a protracted restructuring that required a separate China–Congo-Brazzaville restructuring. China raised similar complications in the 2021–23 Suriname restructuring, in which China refused to provide financing assurances to unlock IMF funding. Empirical research has found a positive relationship between a proxy for IMF negotiating complexity and stocks of Chinese debt. More tangibly, many Chinese loan agreements explicitly exempt the debt from Paris Club restructurings or comparable treatment. On the other hand, the existence of China as an “outside option” may strengthen the position of debtor countries in negotiations with the IMF. In short, the balance of evidence suggests that the presence of Chinese creditors in a sovereign restructuring makes the resolution of that debt crisis protracted, complicated, and costly, relative to Paris Club alternatives.

Does Chinese sovereign lending safeguard debtor sovereignty to a reasonable extent without creating substantial political distortions?

Some scholars have noted that, since the very inception of Chinese lending, it “has always had a strategic element.” It is worth noting, however, that geopolitical strategizing in official lending operations is rather the rule than the exception, and is a practice widely shared across all major creditors for the past 200 years. So here again, the question is whether or not Chinese overseas official lending has disproportionate political distortions relative to the benchmark.

Some studies suggest considerable political leverage. There are, for example, cases of China conditioning access to its PBOC swap lines to South Korea and Mongolia on geopolitical demands, the former with respect to Seoul’s decision to host an American missile defense system and the latter with respect to a visit from the Dalai Lama. However, whether or not that political leverage is more intrusive to sovereignty than, for example, IMF directives about privatizing state-owned companies, is unclear (and that is a high threshold).

One aspect of official Chinese lending, however, that would surpass even the high bar set by strict conditionality programs of the IMF is lending with sovereign collateral, subject to Chinese repossession in the case of default. Yet, these allegations are often exaggerated and misunderstood. Take the much-maligned and misunderstood Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka. There was no debt-for-equity swap, as is often mistakenly portrayed. Chinese SOEs did not “repo” the port—they negotiated a lease-back, which provided Sri Lanka hard currency cash flows and fiscal space to pay down maturing debts. And in both of the most-cited cases of borrower victimization—Malaysia and Sri Lanka—the at-issue debt programs were initiated by the borrowers, not by China. In many cases, the so-called “debt-trapping” is rather a request by a borrowing country for Chinese finance to support a project of questionable economic viability—not because of self-defeating grand strategy, but simply poor planning, limited capacity for sophisticated analysis, and poor governance.

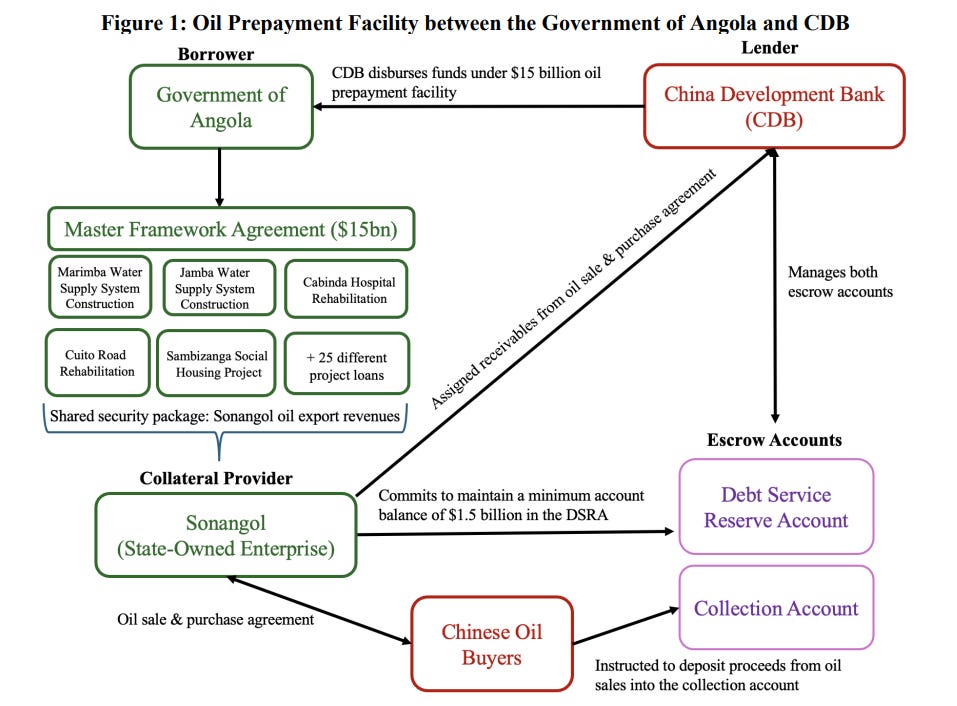

More common than sovereign land or mineral collateral, in fact, is transactions that allow Chinese creditors to ringfence foreign currency cash flows from debtor countries (e.g., offshore bank deposits, export receipts). In fact, per the authors of a forthcoming exhaustive study of official Chinese lending practices, “contrary to popular stereotypes, physical assets back only 8% of the secured debt in our dataset; bank deposits and revenue streams account for the bulk of the collateral.”

Illustrative example of Chinese official loan collateralization: China Development Bank and Sonangol

Does Chinese sovereign lending limit or obstruct other lending?

China’s lending complicates lending from other creditors through two channels: data opacity and restructuring complexity.

Data opacity

Opacity in Chinese lending creates numerous problems for other lenders. For the private sector, ambiguity about debt loads and interest expenses makes asset valuation challenging. For the official sector, similar challenges lurk with respect to debt sustainability analyses. Creditors rely on accurate and complete data on a prospective borrower’s financial health to extend credit.

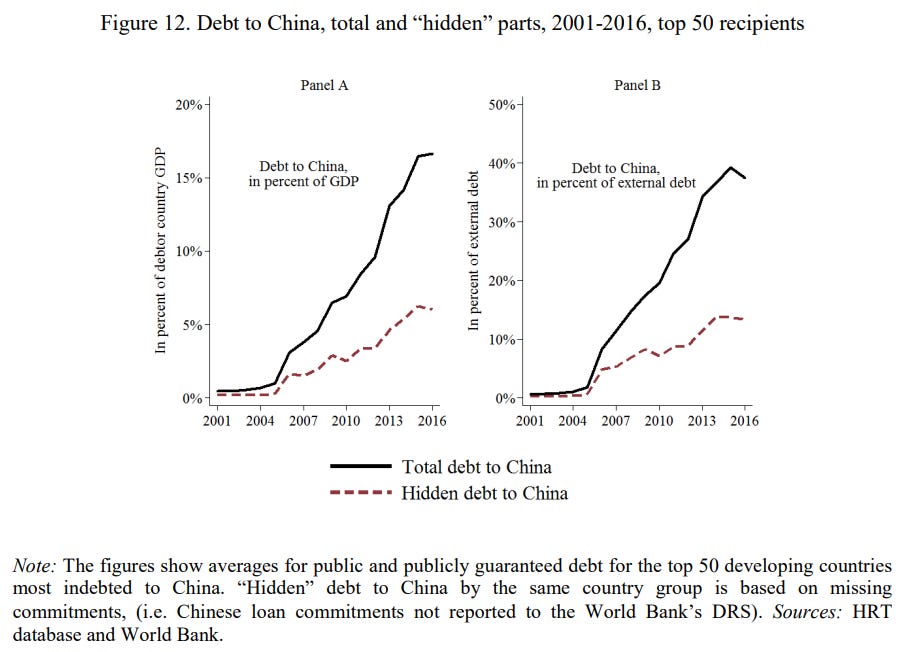

Clear, timely, accurate, and accessible data on Chinese official lending is almost impossible to come by. China does not report its international lending activities—not to the public, not to credit rating agencies, not to the OECD’s Paris Club or Creditor Reporting System or Export Credit Group, and barely even to the Bank for International Settlements. Its lending is also not covered by major commercial providers. The PBOC hardly reports any of its lending via swap lines and deposit facilities; one study including information on PBOC swap line interest rates relied on a leaked digital photograph of a paper copy of the agreement. The primary, if not only, resources on China’s overseas lending are compiled by academics, some of whom report that they expect their estimates to capture only 50–65% of total Chinese overseas loans. So opaque is China’s official lending that scholars have referred to it as “hidden debt.” One estimate suggests that, as of 2019, nearly half of China’s lending is unreported.

Chinese lending opacity

Horn et al. 2019 (25)

This hidden debt is not immaterial: accounting for it dramatically changes the debt loads and debt-servicing costs of dozens of mostly poor countries in magnitudes not previously understood.

Restructuring complexity

China’s role in restructuring has presented challenges beyond simply refusing to provide financing assurances in advance of IMF funding; restructuring challenges are exacerbated by the number of creditors involved and the complexity in bringing them all to the table. For example, in the 2018–19 Congo-Brazzaville restructuring, the IMF approached the PBOC for financing assurances, but the debt was in fact mostly owed to China Eximbank and China Development Bank, over which the PBOC in fact has very little control; not even the IMF knew which Chinese organizations were owed what or answered to whom. In fact, scholars focused on China’s role in sovereign restructurings suggest that one of the most effective avenues to improve sovereign debt restructuring vis-à-vis Beijing is for China to create a consolidated entity to handle and negotiate impaired debts.

Conclusion: Almost There

Has China’s overseas development lending been a net positive for global welfare?

On balance, in the absence of other “better” options, Chinese sovereign lending would be a net welfare positive. However, in light of more transparent and accountable borrowing avenues, including through multilaterals, other official bilateral creditors, and bond markets, Chinese lending does not provide a net gain. Moreover, Chinese lending practices have negative externalities with respect to other lenders: lending practices create asymmetric information that makes it materially more difficult for other lenders, including official multilaterals like the IMF, to provide financing.

Put differently, the answer to our question is: “in nominal terms, yes; in relative terms, no.” That conclusion need not be forward-looking. With simple changes to improve transparency through disclosure, China would accomplish much. A more centralized approach to lending programs, streamlining hiccups along the way, would reduce many of the largest frictions. The straightforward introduction of a competitive tender process for financed projects and the use of local contractors would go far in improving net benefit. The issues that limit the effectiveness of China’s development lending are not so much debt trapping or geostrategic reach, but rather relatively prosaic issues of bureaucratic complexity, lack of identifiable responsibility, cronyism, and opacity. These are solvable issues that Beijing will hopefully address. The world would be better for it.

A central bank swap line is an arrangement whereby central bank A lends its currency to central bank B in exchange for central bank B’s currency as collateral, with an agreement to reverse the trade at a specified future date and exchange rate (which accounts for the interest on the loan).

For our purposes here, reasonable alternatives include, to varying degrees, the IMF, the World Bank, official bilateral creditors (e.g., the US Development Finance Corporation, Japan, etc.), other multilaterals (e.g., Asian Development Bank, African Development Bank), capital markets (e.g., bond issuance), and commercial lenders.

In a Chinese circular lending arrangement, the Chinese lender disburses funds directly to the Chinese contractor doing the work that is being financed. In this way, the funds never actually leave the Chinese financial system, despite creating a foreign obligation from the debtor.

Correlation of course does not prove causation: it could be the case that China simply lends more to already fragile borrowers, not that its lending makes those borrowers more fragile. But it’s an indicative datapoint.