Vignettes of a Currency

Saleha Mohsin’s account of the people and politics of the US dollar

Readers of this site will be familiar with its interest in the collision of geopolitics and finance. Often (but not always), consequential decisions in international financial policy are also informed by, or sometimes result in, domestic political economy. In a new book, Paper Soldiers (link here), Bloomberg journalist Saleha Mohsin tracks both the foreign and the domestic political economy of the US dollar over time, which is naturally a story we are interested in.

In this note, we’ll explore the main upshots of the book. This is not a book review per se, but a summary of its key themes, stripped down, and summarily dressed up with footnotes (sorry not sorry). The book is not technical, by design; the financial literati among my readers may find the lack of discussion of the Eurodollar market and BIS-coordinated foreign exchange interventions of the 1960s to be wanting. But the book’s aim is not to lay out, in detail, the technical infrastructure of the dollar system. Nor is it a tome of America’s monetary history. The aim of the book is to highlight the people and the political consequences of the dollar’s strength—both its literal strength in foreign exchange markets, and its dominance as the world’s key reserve currency.

Some Sweeping Generalizations

If I had to summarize the key takeaways from the book in three points, they would be the following: (1) the foreign exchange value of the dollar has immensely important—but under-appreciated and not widely understood—consequences for the domestic political economy of the United States; [1] (2) the “weaponization” of the dollar—its use as a means to geopolitical ends—has consequential effects on the international order and the foreign policy landscape in which the US operates, and poses risks to the hegemony of the dollar system (this latter claim is more debated in the field); and (3) the stewards of the US dollar—namely, Treasury secretaries and the unsung heroes of Treasury’s professional (read apolitical) staff—remain extremely important guardians of the dollar, from risks both foreign and domestic, and do more to insulate the dollar from political meddling than we give them credit for. We’ll focus here on the first two, but indeed, our dedicated public servants are consistently under-appreciated and Paper Soldiers makes a laudable effort at highlighting the professionalism, seriousness, and importance of the work done by the people of the Department of the Treasury.

Claim (1) is interesting and something we haven’t talked about here. Claim (2) is also very interesting, if not more hotly debated. Claim (3) is likewise interesting and perhaps an important story for many Americans to hear at a time when politics can feel tone-deaf.

Strong Dollar, Weak Communities?

We are all probably familiar with the following narrative, which goes some way in explaining the rise of populism in the US: (1) we used to have thriving manufacturing jobs in the US, which (2) was very nice and lots of blue-collar workers had reliable incomes, which resulted in nice towns and communities for non-college-educated folks, and then (3) globalization took root, those jobs were shipped abroad (cue usual bugbears of globalization: China, NAFTA, et al.); (4) the nice stuff from point (2) evaporated, and the heartland of the US was hollowed out as jobs, and the livelihoods, communities, and dignity that came with them, collapsed. While policy experts may disagree on the magnitude of that story and the role that other factors, like technological changes, may also have played on US manufacturing jobs, there is broad-based consensus now (even across the aisle) that unbridled trade without compensation for the “losers” of it has been extremely damaging to erstwhile manufacturing communities and the demographics that were employed in them.

What does the dollar’s foreign exchange rate have to do with this? A lot, probably. Of course, there are lots of other relevant things here (e.g., dumping, WTO rules, China’s entry into the WTO, other state subsidies, tariffs, etc.) that the book doesn’t get into, but its point is that the exchange rate of the dollar plays an important role in America’s trade balance, which, to macro folks will seem obvious, but to everyone else may fly under the radar.

Sidebar: Foreign Exchange and Trade—How It Works

(Macro folks, skip this section.) Here’s the easiest way to wrap one’s head around it: You’re an American, and you want to buy a Kinder Bueno bar (of course, who wouldn’t) from Germany. The candy bar costs €1; you have $4. If $1 = €1 (neutral), then you can buy four chocolate bars with $4. If, $1 = €2 (strong), then you can buy eight chocolate bars, because your $4 gives you €8 of purchasing power. If $1 = € ½ (weak), then you can only buy two chocolate bars, because your $4 gives you €2 of purchasing power. Reductively, as the dollar gets stronger, imports get cheaper because for every one dollar an American has, it buys more units of foreign currency, which means it can buy more units of goods and services denominated in that foreign currency.

The flip side to this is also true: let’s imagine this from the exporter’s perspective. For a foreign exporter, a strong dollar results in higher demand for foreign goods from the American consumer, so this is good for them. If you’re a Turkish exporter of (the world’s best) coffee, your business is going to do more exporting when the dollar is stronger, since there will be more demand from America for your coffee. Again, the flip side to this is true in the US: if you’re a US exporter and the dollar is stronger, then you will do less exporting, because people in foreign countries importing your goods end up paying more in their local currencies (which of course are the currencies they receive their salaries in, and therefore determine their buying power). [2]

If you are an exporter of steel from, say, Pennsylvania, and you export one unit of steel for $100 to Thailand, it might cost the Thais (I’m making this up entirely, explanatory purposes only, not real FX rates) 1,000 baht. You don’t see that or care about it necessarily, but you know that you produce a bar of steel and get paid $100 for it. But if the dollar appreciates, even though you haven’t changed your price, your $100 bar of steel may now cost the Thais 1,500 baht. If they can stomach that, then fine, you still get $100 for the bar you made. But in all likelihood, they can’t stomach that, or won’t, and their demand will concomitantly decrease. You’re used to selling ten steel bars to the Thais, but now they only want eight of them, or they’ll take ten but they have to offer you less than $100 per bar. If you the steelmaker can’t manage that, then the Thais will start buying their steel from some other country that can do it more cheaply, which, as we’ve seen, is in no small part a function of the exchange rate. [3]

How directly can one draw a line between the exchange rate of the US dollar and the life and death of great American manufacturers (Jane Jacobs fans, anyone?)? This book isn’t a work of empirical inquiry, and there are empirical works that try to quantify that relationship (see, e.g., the IMF). What Mohsin is trying to get at is the political salience of that relationship. And there are some pretty telling vignettes in the book that indicate Americans are well aware of its power. Take, for example, this story of a West Virginia steel town (pp. 56–59, emphasis mine):

Launched by Earnest T. Weir in 1909, Weirton Steel found early success and became the lifeblood of the local economy, a quintessential tale of the American dream . . . But by the late 1990s, the city and its 20,000 inhabitants had come upon hard times. The workforce of the local mill, run by Weirton Steel, was down to 3,500, roughly a quarter of the peak employment. Unemployment averaged about 9 percent in the region . . . Thousands in the town of Weirton marched across the streets shouting, “Save our steel!” . . . “It’s time for a new dollar policy,” Tom Palley of the AFL-CIO federation of labor unions said at the time. “[The United States] needs to stop this strong dollar rhetoric and replace it with a sound dollar policy” . . . Before long, the town of Weirton was practically empty and made up of haggard shopping centers, strip clubs, and poker bars . . . The demise of Weirton reveals the cost paid by American workers of a policy preference for a strong exchange rate and the principles of free trade that authenticate it.

Now, there’s more going on here than the exchange rate, which Mohsin readily acknowledges (e.g., free trade deals), and of course the flip side of concentrated export losses was diffuse import gains (i.e., Americans across the country enjoyed cheaper imports because of dollar strength too). Nonetheless, that there were street protests featuring stump speeches about America’s foreign exchange regime struck me as oddly politically salient. That’s Mohsin’s point: while the dollar exchange rate policy probably strikes the contemporary reader as an esoteric issue confined to the halls of academia, it was highly salient to Wall Street, exporters, labor unions, and bond traders.

This all begs two questions: (1) why did the US pursue a strong dollar policy and (2) is there anything that can be done about it (i.e., can the US weaken the dollar)? If you’re really interested in these questions, I’d recommend reading the book. The long and short of it is the following:

On the strong dollar. First, it’s worth bearing in mind that the strength or weakness of a nation’s foreign exchange regime is only partially a function of policy choices, insofar as natural market forces move the exchange rate, and the government can attempt—to varying degrees of success—to respond (or not) to those movements. To the extent that a given targeted exchange rate (or band of exchange rates) is a policy choice, there are trade-offs to be made. For example, a famous postulate of international financial economics is that a nation can choose (at most) two of the following, but never all three: control over its exchange rate, an independent monetary policy, and free capital flows (for more on this, see this column). [4]

With that ground-clearing out of the way, the US support for a “strong dollar” began not so much as an active intervention policy, but rather the opposite: a turn away from actively intervening to keep the dollar weak. A stronger dollar was, in many ways, an acceptance of reality. While the US had been able to successfully coordinate with other nations to buy and sell dollars in order to move its exchange rate, [5] it had begun to run out of firepower to do so (ironically, early post-war interventions such as the secretive Plaza Accord [6] were, in large part, responses to the same concerns about a strong dollar as those echoed in Weirton, West Virginia, many decades later).

Persistent fears of American authorities’ meddling pushed prices on Treasury securities down (to reflect the increased risk that the US currency would be devalued by interventions), meaning that it pushed their yields up, i.e., America had to pay more in interest to finance its own deficits. Since Treasury securities are the benchmark for nearly all American interest rates, this translated into more expensive mortgages, student loans, and business credit. Eventually, the bond traders had scared policymakers enough that they abandoned managing the dollar’s exchange rate and were at pains to publicly state their intention to leave it alone (around this time, famous trader George Soros had launched an offensive on the British pound so severe that it felled a government [7]). This too came with political optics: the perception that American authorities had caved to the “bond vigilantes” at the expense of Main Street wasn’t winning friends in blue collar America.

On the possibility of intervention. There’s not much in the open market that the US can do now. Foreign exchange intervention is very difficult, and it’s particularly difficult when, per the trilemma mentioned above, your nation has no capital controls and wants to have some autonomy over its monetary policy. The US historically bought and sold dollars in coordination with nations like Japan and West Germany in the post-war era (it also employed central bank swaps [8] to do so), but its reserves (in a multitool of a money pot called the Exchange Stabilization Fund, or ESF) used to be much larger relative to the amount of outstanding dollar assets. Today, using the ESF to intervene in the dollar’s exchange rate would be like the Dutch boy putting his finger in the dike: it might help temporarily, but larger forces would ultimately prevail. Arguably, the fact that the Plaza Accord, though it worked, required multinational coordination was itself evidence that the US alone could hardly move the dollar. By 1992, a US currency intervention required the actions of eighteen central banks: dollar flows relative to the size of the ESF had simply gotten too big to manage unilaterally. [9]

Today, unless the US wanted to give up its monetary policy or implement capital controls, lasting foreign exchange intervention would be difficult. For more on this, see Treasury veteran Mark Sobel. Even if there were desire to conduct a short-term intervention, questions remain about whether or not it would be politically feasible. Administratively, and in an interesting hypothetical about central bank independence in the US, it is ostensibly possible that the Federal Reserve would simply refuse to go along. When and if the Treasury wanted to go about transacting in the foreign exchange market, it would do so through its agent, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY). Some believe that the FRBNY might refuse to comply with such instructions if it viewed them as politically motived rather than for reasons of market stability (the Federal Reserve has historically refused to comply with requests from the executive branch that it views as politically motivated, such as Donald Trump tweets demanding lower interest rates).

The Logic of War in the Grammar of Commerce

Sanctions and their use (misuse? overuse?) have been a topic du jour recently, one that we’ve touched on nearby (see here and here). Mohsin provides a colorful history of their use and deployment, told through the eyes of the individuals—mostly, the men and women of the Treasury—who developed and deployed them.

First, though, a useful reminder that currencies (by which here we mean sovereign control of money) play another critical role in war and conflict: financing wars. Mohsin recalls Abraham Lincoln’s Treasury secretary, Salmon Portland Chase (you may be familiar with a bank named after him), who took the US off the gold standard to finance its war against the Confederacy (pp. 17–18):

To keep President Lincoln’s two million Union troops active, Chase needed paper . . . The idea of a certificate that offered no interest payments and was not redeemable for gold or silver was, at first, viewed as all but sealing the ruin of a country only just created, and making its stewards look like a “carnival of rogues.” . . . But as soon as the radical idea became law with Lincoln’s signing of the Legal Tender Act, the new paper currency immediately lubricated the market for government credit, galvanizing the nation’s economy and the Union Army. The universal acceptance of the greenbacks [. . .] made them far superior to notes issued by the South. If anything, the penetration of Lincoln’s currency into the South heralded the demise of the Confederacy . . ..” [10]

Fast forward over a century, and the Treasury sharpened the dollar into the modern weapon of conflict that we know it. [11] The first national security response to the terrorist attacks of 9/11 was not a military one, but a financial one. [12] In a chapter entitled A War Room for Treasury, Mohsin tells the story in gripping human detail (pp. 72–74):

For essential workers like [Treasury secretary] O’Neill, the federal government had arranged transport [from Tokyo] via C-17 military jets, the kind made to move cargo to areas of conflict . . . When they landed at Joint Base Andrews, a military facility fifteen miles away from the Treasury department, Michele Davis looked out and saw hundreds of members of the armed services surrounding their plane, machine guns in hand . . . [On September 24, 2001] with O’Neill and Secretary of State Colin Powell at either side, Bush announced that “with the stroke of a pen” at 12:01 that morning, the war on terrorism had begun. He told the world he was attacking “the financial foundation of the global terror network” by using the dollar’s power to punish the nation’s enemies. Using a combination of legal authorities for national and international emergencies, he issued an executive order that immediately gave the Treasury the ability to block and freeze U.S. assets and transactions with individual terrorists, terrorist organizations, or those known to associate with them.

This isn’t the end of the story, as Mohsin tracks the use (overuse?) of sanctions since 9/11, showing their methodical expansion both in quantity and in reach. By 2022, the US had honed the craft into “economic blitzkrieg” (pp. 232–233):

Adewale “Wally” Adeyemo, the number-two official at the U.S. Department of the Treasury had cancelled his Christmas and New Year’s holiday to help draw up this contingency plan. By the time the war broke out, Adeyemo had finished reading A Gentleman in Moscow, a fictional account of a poet imprisoned in a Moscow hotel in the 1920s for penning a revolutionary poem. As it became painfully obvious that U.S.-Russia relations were forever damaged by the events of 2022, Adeyemo would later remark how as he read the book against the backdrop of the war, he realized he would never be able to walk the streets on which the tale unfolded . . . Adeyemo and Singh [Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economics] had unleashed a full slate of the most painful economic sanctions ever imposed. Some days later, Putin himself would refer to it as an “economic blitzkrieg.”

There is a fundamental tension here that Mohsin teases out: the greater the ubiquity of the dollar, the more potent the sanctions; the more potent the sanctions, the greater the incentive for others to ditch it, attenuating the very ubiquity that gave it the sanctioning power in the first place. This dynamic has been supported empirically elsewhere, notably by Daniel McDowell in his research compiled in Bucking the Buck, a book covering this very topic.

Perhaps the paragon of the have-we-overdone-it concern with respect to sanctions is the recent (and relatively [13] unprecedented for modern times) freezing of the Central Bank of Russia’s (CBR) reserves in response to its invasion of Ukraine. While it’s perhaps easy to think reductively in terms of crime and punishment (pun very much intended), the idea of freezing a sovereign nation’s reserves was and, to some degree, remains a contentious issue in Washington, not so much for fear of Russian ire (which was in fact the point), but because of concern about the effects such a move would have on a global public good: reserves management. Would other nations begin to think the same could happen to them and shift out of the dollar? McDowell (op. cit.) delves into this issue and convincingly argues that, yes, numerous nations have begun to diversify their reserves away from the dollar when conscious that they may be a future target. [14] Again, Mohsin narrates the story in captivating human detail (pp. 236–237):

On Saturday morning, they were all moving closer to enacting the largest economic sanctions ever levied [against Russian’s central bank] . . . But one person stood in the way: Janet Yellen. She was worried about what these actions would do to the dollar. Her main concern was that there was a risk that foreign central banks would start to doubt the United States as a safe place to store assets if that money could be put out of reach through sanctions, which would erode the dollar’s standing as the world’s bedrock currency . . . To smooth things over with the Treasury chief, Singh and his boss, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, took the unusual step of arranging for a foreign leader to persuade the U.S. secretary of the Treasury on their behalf. With the help of the European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, who was also frustrated at the holdup in the United States, by around 1:00 p.m. on Saturday the group was able to get the Italian prime minister Mario Draghi [an old friend from central banking days] to call Yellen directly in her office at Treasury.

Of course, Draghi did whatever it took (sorry, too easy) and persuaded Yellen. But the unease over the weaponization of the dollar continued. As I write, the US and EU continue to debate what they ought to do with those frozen reserves, with some arguing for seizing them entirely (remember, sanctions only freeze them, but they’re still the property of the target—a strategy meant to induce desired behavior so that there remains a reward for complying), while others view this as a step too far, and yet others offer compromise options. [15] As the dollar has become an increasingly potent and frequently used weapon, the debate over its role as a geopolitical tool is nowhere close to over.

Of Currency Wars and War Currencies

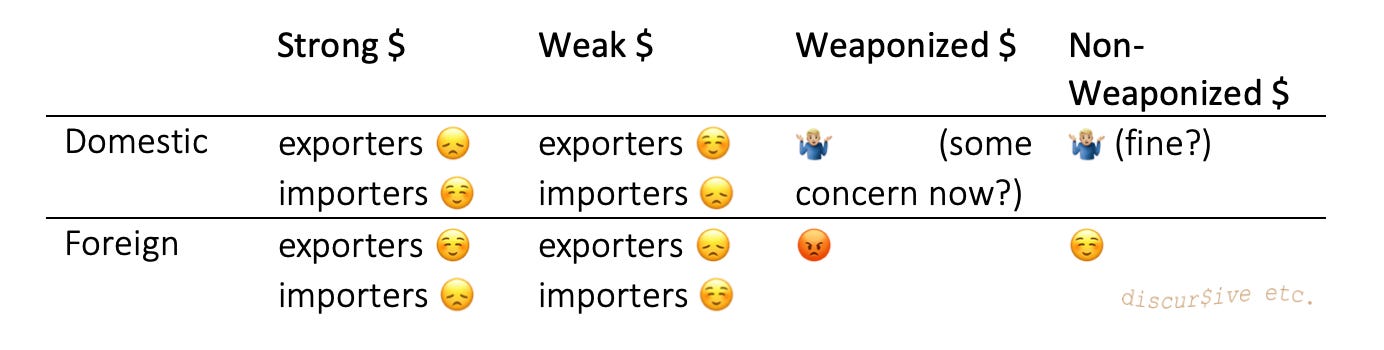

In summary, I think the following table very roughly captures the ideas, cutting across the two primary dimensions of (a) foreign exchange strength and (b) geopolitical “strength” (weaponization):

Paper Soldiers is a reminder of a theme this site is interested in: that some of the most important and consequential macroeconomic and financial questions are deeply and inextricably political—sometimes geopolitical—questions. There is, of course, more to the dollar’s strength and reserve status than Bretton Woods, but reductively the dollar standard borne of the postwar settlement has paved the way for its strength, both in terms of its foreign exchange rate and its international standing. The sundry challenges and benefits those strengths pose—from the ability to block adversaries from dollar payments to a disadvantaged export sector—are in many ways the long shadows of Bretton Woods, and thus another part of the modern world deeply informed by its own history of conflict and great power struggle.

I am grateful to Carey Mott for his valuable comments.

If you want to discuss this further, please reach out: vincient.arnold@yale.edu

You can also follow me on Twitter (X) @ArnoldVincient, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

This work is independent from and not endorsed by the Yale Program on Financial Stability or Yale University; all views are my own.

[1] Not mentioned in the book, and probably not all that critical from a population share perspective, is the point that many countries, territories, and protectorates that are not the United States use the US dollar as their currency, either de jure or de facto (e.g., Ecuador, Panama, East Timor, Somalia). The dollar’s exchange rate of course affects the domestic (but kinda foreign?) political economy of those nations too. This is all not to mention those nations one step removed, which, by nature of maintaining various degrees of strict pegs, have currencies that in effect track the dollar’s exchange rate very closely (e.g., Emirati dirham, Hong Kong dollar).

[2] This is the “trade competitiveness channel”; there is also a less-discussed financial channel, whereby a stronger dollar results in tighter dollar funding conditions, which in turn depress trade writ large (see Shin and Bruno 2021).

[3] This phenomenon plays a role in the financial crisis world I work in for my day job. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, countries otherwise similarly positioned saw differential recovery rates in part because of their exchange rate regimes. For example, both Iceland and Ireland were severe casualties of the crisis, but Iceland’s freely traded króna was able to depreciate, helping to boost Icelandic exports (which, remember, can include services, like tourism). In contrast, Ireland was unable to equilibrate its exchange rate, since it was a member of the Eurozone, and had a more challenging recovery.

[4] A stripped-down version of the logic states that freely mobile capital chases yield: if I can earn a higher interest rate (because of monetary policy) on British assets than American ones, then I sell my dollars (probably in the form of Treasury securities) and buy British pounds (probably in the form of British government debt). This flow of supply—dumping dollars and buying up pounds—drives the dollar to weaken against the pound; in other words, it alters the exchange rate. Of course, if there are capital controls, maybe I can’t legally do any of this ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ hence the trilemma.

[5] Think of it this way: if you buy up dollars, there are fewer available on the market. Just like a used car lot with limited inventory, the supply reduction results in an increased price—in the case of a currency, that’s an appreciating exchange rate. Likewise, if you dump currency onto the market, the supply increases and the price (exchange rate) drops.

[6] The Plaza Accord was a coordinated foreign exchange intervention to depreciate the US dollar, enacted jointly between the G5 countries in 1985, named so because the secretive meeting planning the operation took place in the Plaza Hotel in New York. For more on this, see Jeffrey Frankel.

[7] Needless to say, there wasn’t serious concern that the US would suffer the same fate (for numerous reasons and, contextually, the UK was a maintaining a band in which it actively managed the exchange rate), but the story is instructive insofar as foreign exchange interventions can be costly and politically salient: British taxpayers were estimated to have lost $3.8 billion in the Bank of England’s interventions defending the pound. For more on this, see Mallaby, More Money Than God, Ch. 7.

[8] This occurred primarily in the context of the gold standard, whereby the Federal Reserve would supply dollars to foreign central banks to forestall the liquidation of dollar reserves abroad into gold at the Treasury’s gold window, thereby defending its gold reserves and thus the dollar-gold peg. For more on this, see Bordo, Humpage, and Schwartz; see also Arnold and McCauley and Schenk.

[9] For more on this, see Mallaby, More Money Than God, pp. 157–158.

[10] In contrast, while the Confederacy also issued fiat currency, it succumbed to hyperinflation in a monetarist textbook case. For more, see the Richmond Fed’s concise history. For more on the financing of the civil war generally, see here.

[11] This was not, however, the first use of sanctions by the United States. Depending on how one defines American sanctions, the US has used them during World War I; it also used sanctions during World War II, the Cold War, and to put pressure on the apartheid government of South Africa, among others. For more on their history, see here.

[12] More immediately in the financial realm, the Federal Reserve assured markets that it stood ready to lend and stood up dollar funding swap lines to major global central banks to backstop offshore dollar funding markets. For more, see French 2023. The provision of emergency dollar liquidity worldwide via swap lines and repo facilities is another important aspect of the geopolitics of the dollar, one that merits a separate discussion.

[13] The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)—the sanctions office at Treasury—has frozen the sovereign reserves of a nation once before that—against the Central Bank of Libya in 2011. Much longer ago, the US also froze the assets of enemy nations during World War II.

[14] There’s a lot of nuance to this, though: among other things, (1) the number of nations doing so is small; (2) a lot of reserves diversification away from the dollar has nothing at all to do with sanctions; and (3) as explored in depth by Federal Reserve economic Colin Weiss, even if reserves splintered geopolitically, it probably wouldn’t change the landscape all that much (i.e., most major dollar holders are US allies anyways).

[15] There’s too much to get into here, but see Setser for a nice synopsis of the debate and some of the policy options available.