Dispatch No. 3

A roundup of learnings

Changing the name from ‘reading list’ because…I don’t know, I think I like this more.

Golden Parachute: Financial Sanctions and Russia’s Gold Reserves. Daniel McDowell. Istituto Affari Internazionali.

This piece focuses in on the Russia’s gold strategy, and expands on work McDowell has done in his book Bucking the Buck. Here he focuses on gold’s value as a sanctions hedge—a uniquely geopolitical consideration. A nice top-line (my emphasis):

Moscow’s rekindled love for gold is a direct result of the accumulation of US financial sanctions programmes targeting the Russian economy between 2014 and 2021 . . . Russia’s gold holdings were no panacea for the Kremlin in the face of these severe sanctions, but unlike CBR’s dollar and euro holdings, its bullion remained under Moscow’s control. I argue that gold reserves helped Russia in two distinct ways during the early days of the conflict. First, evidence suggests that Russia sold some of its bullion early in the conflict as a means of acquiring foreign exchange– something feasible, despite sanctions, because the physical nature of gold makes it possible to hide its origins. Second, as the ruble’s value crashed in March 2022, the Russian government implemented policies to encourage citizens worried about their savings to buy gold. Many Russians heeded this advice. In this way, Russian gold reserves operated as a de facto anchor for the ruble. This may have made severe capital outflow restrictions, which blocked off investments into foreign currency assets, more palatable to Russian savers.

I learned for the fist time about Russia’s sales of some of its gold holdings—likely at a serious discount—in non-traditional markets (some suspect Dubai) and China to support the ruble and its invasion of Ukraine. Also novel to me was the state support for ruble-for-gold sales domestically to blunt the wealth effects of capital controls on Russian savers.

He makes an important point about physical gold, preempting the critique that it’s non-yield-bearing and illiquid. While I’m putting this in my words, my read of his comments is that gold has a payoff structure somewhat like buying far out-of-the-money put options: totally useless in most states of the world—and costly—but immensely valuable in the far left tail. In other words: an insurance policy you pay non-trivial premia for, but for which the coverage makes it make sense, especially to highly risk averse organizations, like sovereigns.

This is awesome paper, worth reading in full; you’ll be rewarded with fun nuggets like this: “Russia used a paramilitary organisation known as Wagner Group to craft ties with regimes in several destabilised, conflict-prone African countries. By providing security services to embattled military leaders, Wagner accepted payment in gold which was then transported by air to Russia” (my emphasis; citations omitted). 10/10.

ICYMI, we’ve discussed this topic, in the context of rising gold prices, around here:

Influence by omission: The IMF’s lending capacity and central bank design. Ana Carolina Garriga and Michael A. Gavin. SSRN.

Lender of last resort (LOLR) meets IMF cross-over episode? All in. Here’s a nice top line (my emphasis):

In this article, we show that declining prospects for international assistance in times of crisis and continued efforts to boost the capabilities of domestic central banks are subtly connected. Unlike existing research which shows how the IMF influences countries by commission, such as through its lending practices, recommendations, and especially loan conditionalities, we argue that the relative size of the IMF’s lending capacity influences states by omission. Our argument in brief is that the inability of the IMF’s lending capacity to match the growth of financial globalization is noticed by the IMF’s potential borrowers and that states respond by strengthening the capabilities of their central banks to combat crises, especially to act as more capable lenders of last resort.

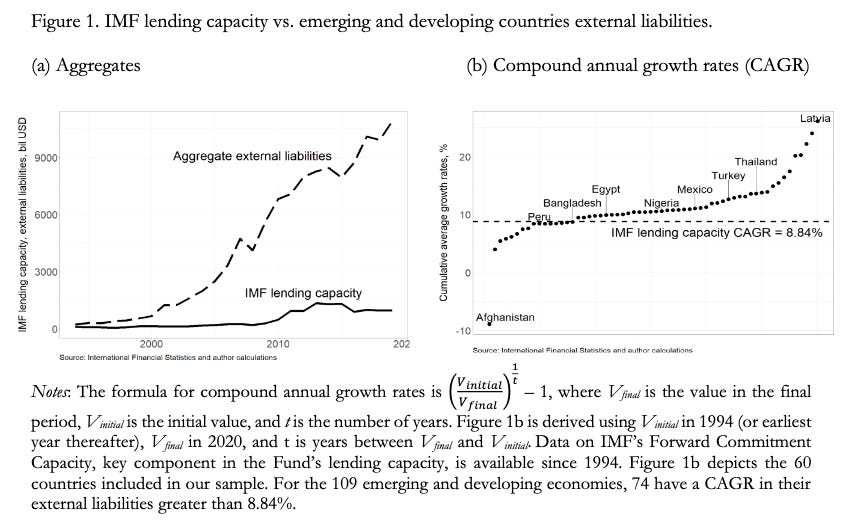

The authors carefully trace the evolution of the IMF’s lending capacity, showing it to decline in size relative to aggregate external liabilities over time. E.g.:

Then, through compilation and analysis of an extensive dataset on LOLR authorities and illustrative case studies like the Bank of Thailand, the authors provide evidence that central banks have filled the gap themselves, preemptively boostrapping their way out of the IMF lending void. They employ standard OLS regression with fixed effects to assess the impact of lower IMF borrowing capacity (relative to external debt stock) on country (okay, monetary authority, sorry) LOLR capacity, with significant results. Finally, they do an event study of the COVID-19 crisis and response, further supporting their hypothesis.

Sovereign Debt Restructuring with China at the Table: Forward Progress but Lost Decade Risk Remains. Gregory Makoff, Théo Maret, Logan Wright. Harvard Kennedy School.

I am a seasonal dilettante in the sovereign debt universe, but these three gentlemen are decidedly experts. This piece does an excellent job highlighting and synthesizing China’s changing role in the sovereign debt landscape over time. For one, it is a useful corrective for Western readers to appreciate the magnitude of Chinese sovereign lending in recent decades: “China’s lending to developing countries has rivaled that provided by the G7 since 2000, and it has had a significant concentration in many of the poorest—former HIPC [highly indebted poor countries]—countries” (my emphasis).

They trace the numerous motivations, geopolitical and otherwise, that drove China to engage so aggressively in this lending, and summarize recent challenges in Congo-Brazzaville, Suriname, and Zambia, and the infrastructural changes made by major Paris Club members and the IMF in response to those challenges.

Perhaps the most interesting addition of the piece is to examine why China struggles so hard to grant debt relief to highly indebted countries, which the authors explain is largely related to China’s internal domestic political landscape and incentive structure, which they sum up pithily as “loss avoidance and institutional complexity.” The authors make a compelling point that China’s administrative foot-dragging on permanent debt relief may risk repeating a lesson we’ve already learned:

China’s position on sovereign debt restructuring, and its significant sway as a large lender, risks a repeat of the lost decade of the 1980s, when international banks insisted on “extend and pretend” restructurings to avoid taking losses. In that period, U.S. banks were so exposed to what was then called Less Developed Country (LDC) debt that they couldn’t afford to take losses. To protect them the U.S. Treasury, the Federal Reserve, and the IMF developed economic plans that assumed sufficient growth to pay off the existing debt. The growth never materializing, this led to serial debt restructuring, which didn’t end until the 1990s, when the countries carried out Brady restructurings with significant debt relief. The Brady plans were a success. After these restructuring nearly all the Brady countries thrived, using the opportunity to reform and improve financial governance to avoid ever going into debt default again. (citations omitted)

They finish with a pragmatic policy recommendation inspired by China’s own handling of its 1990s banking system bad loan problem: that China create a single unified specialized asset management vehicle to manage its bad sovereign debt assets from its disparate creditors.