Gold, Geopolitics, and Central Banking

taking (physical) stock

Legal stuff: If it is not exceedingly obvious already, none of this is investment advice.

What’s up with gold these days?

A casual glance at a gold EFT (ticker: GLD) will inform you that gold (some imperfect proxy of it, I know, I know) is up roughly 42% from 2023–2024. That’s a lot!

Zooming out for some context, since 2000 gold’s price has increased almost ten times over, outperforming numerous equity indices. More recently, gold has been in the headlines. Here is a smattering (in no particular order):

The Midas touch: 4,000 years of getting it wrong about gold (FT)

What the surging price of gold says about a dangerous world (The Economist)

Soaring gold becomes top ‘Trump trade’ (FT)

Gold Gains as Traders Seek Safety From Latest Tariff Threats (Bloomberg)

Gold stockpiling in New York leads to London shortage (FT)

Gold hits $3,000 for first time on global growth fears (FT)

It’s not just tariffs and the fracturing of geopolitical alliances that’s back again—gold is back too! But, if you take a look at the above enumerated pieces, you’ll see that geopolitics and central banking are central pieces. In this post, we’re going to explore that: how geopolitics and central banks interact, and how that interaction can affect gold prices.

Looking under the hood

But before we get ahead of ourselves, we can always take a look at this empirically and ~run a regression~, everyone’s favorite method, to give us some empirical guardrails and set the scene. Chiang 2022 is really the gold standard (pun intended) for this, but the data is of course limited to the period ending in 2022. So, here goes:

where:

GLD = the SPDR Gold Trust ETF (and therefore an imperfect but sufficient proxy for physical/monetary gold prices, from which ETFs can deviate); GLD sub t represents the gold price at time t, GLD sub t - 1 represents the gold price one period (month) before, and GLD sub t -2 represent the gold price two periods (months) before;

GPRD = the Caldara-Iacoviello Geopolitical Risk Index,1 which measures worldwide geopolitical risk, inclusive both of threats and actions (for more on the index, see here);

VIX = Chicago Board Options Exchange's Volatility Index (d.b.a. “the fear index”), which captures volatility on the S&P 500 equity index (technically, it gauges future expectations of volatility derived from options);

SPX = the S&P 500 index (you’ve heard of her);

USDI = the real broad effective exchange rate for the US,2 as calculated by the Bank for International Settlements;

CPI = median consumer price index, as calculated by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.3

Everything here is logged to smooth the data, and for parsimony we consider period effects only for gold prices.

Running the regression, we get:

So, first of all, and I can’t stress this enough, I am not convinced this is a good model. More sophisticated models assume first-order autoregressive effects and regress changes instead of levels. And, mind you, the regression here is very intentionally limited to start in 2020 (because it’s interesting, post-COVID), so I’d hesitate to generalize much on such a small N. All to say: you’ve been warned!

But it’s a model (that explains roughly 90% of the variation in gold prices for this period), and it does use real data, and the assumptions aren’t awful (the residuals plot is fine, e.g.). Note that four (logged) variables are significant at the p < 0.05 level: the one-period lagged gold price (shocker), the S&P 500, the dollar index, and CPI inflation. The model says some stuff. Here’s a non-exhaustive list (beyond the obvious momentum effect of the one-period lagged gold price):

Of particular interest here is what the model says doesn’t really matter: the VIX and GPRD. First of all, they’re nowhere close to statistically significant; second, even if they were, their intercepts are very small. Now, I’m going to try to convince you that they really do matter anyways, but the empirics have given me guardrails and made that more of a challenge (I need to prove a lurking variable, essentially, which I’ll argue is central bank purchases).

Sidebar, the correlation between the VIX and the GPRD (in this period, of course) is negative 7.2% (on daily data)! This all seems weird? I don’t want to get too into it, but my hunch is that this is because: (1) the VIX is limited to the American stock market (e.g., a terrorist attack in the Eastern Congo might spike the GPRD, but NYSE traders don’t care); (2) the GPRD includes stuff that may not move markets that much even if the subject population were broader than American equity traders (e.g., by construction, it includes threats in addition to events); and (3) the VIX is by construction broader, so while it might encompass geopolitical risk, it’s by definition a catch-all for volatility (which could have to do with non-geopolitical stuff, obviously, like Fed guidance, employment numbers, or a subreddit).

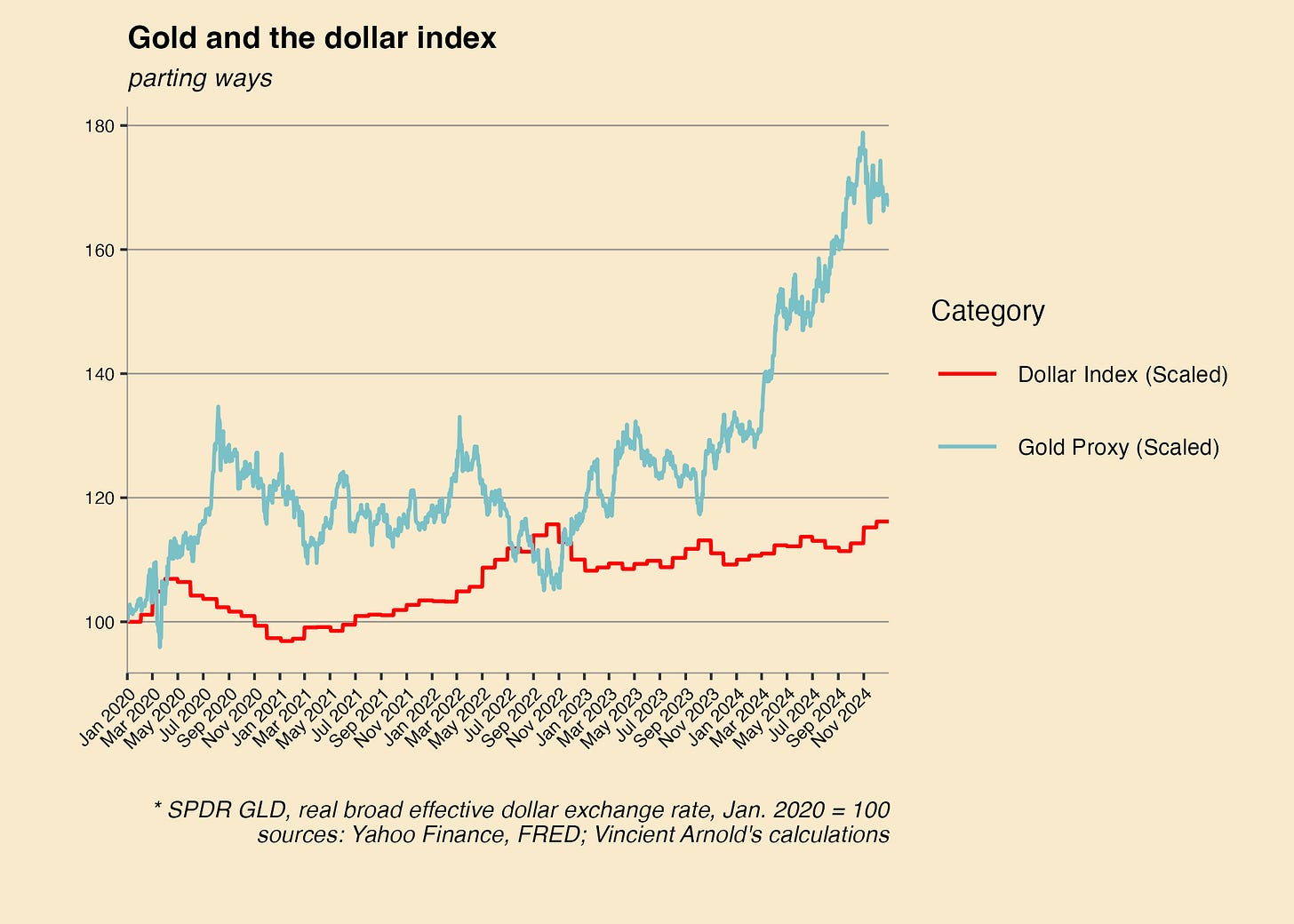

The dollar index matters a fair bit. A 1% increase in the dollar index results in a ~0.4% increase in gold prices. This is all the more interesting because it is contrary to the historic norm. Usually, the relationship is inverse: the two are negatively correlated, and dollar strengthening hurts gold. That’s deductively sensical: when the dollar is stronger, that’s usually because (short-term) rates are higher, so the opportunity cost of holding gold increases. And yet, here we are.

Sidebar: the dollar index is highly correlated (83% in this period, if you use daily data) with short-term rates (hence why I’ve left them out of this model), which is no surprise. I included it here instead of short-term rates because I think it’s probably the more inclusive of the two: the index is calculated on bilateral rates, so it’s also capturing movements in/expectations of other major short-term rates as well (à la interest rate parity). One possibility here is that in this case, short-term rates are higher because of an inflationary environment, and folks are holding gold as an inflation hedge. Or, other stuff just matters more.

The S&P and inflation betas appear inverted relative to expectations. A 1% increase in the S&P 500 index is associated with a ~0.2% increase in gold prices over this period; for CPI, that figure is negative 0.05%. Nothing illegal about that, but typically you hear about gold being used as a hedge against inflation and market dips, i.e., stocks down (sad), gold up; inflation up (sad), gold up. More on this later, but my hunch here is that folks (institutions) are pushing demand for gold high as a result of other concerns. It is also though worth caveating that, again, the inflation and equities data here are not only temporally limited, they are also geographically limited: this doesn’t account for equities moves and inflation around the world (but email me if you want to see that!).

Ultimately, this model leaves us with more questions than answers. Why don’t the VIX and GPRD matter here? Beyond simple momentum effects (lagged gold prices), the model doesn’t tell us a whole lot: American stock prices matter moderately (but in the opposite way we’d expect); the dollar index matters moderately (ditto on inverse expected relationship); and American inflation matters a little. We’d expect to see slumps in stocks and rises in geopolitical risk and inflation to be associated with higher gold prices, but the data aren’t incredibly satisfying. In part, that may be simply down to a not-adequately-sophisticated model, but it’s also possible that there could be (likely are) lurking variables. I don’t claim to have the whole answer, but you can’t talk about gold as an asset class these days without talking about geopolitics and central bank gold purchases.4 Let’s take a look.

Central bank gold purchases: big and getting bigger

Central banks and gold, needless to say, have a complex relationship. This of course is not a blog about the gold standard, or the gold-backed BRICS coin idea that is in vogue. But probably the right way to think about gold and central banks is that central banks are responders to geopolitical risk, but are both responders to and producers of—to various degrees of influence—other variables that impact gold prices, like short-term rates, inflation, and exchange rates. In this section, we’ll discuss the core theme of this note, geopolitics, before turning to the other bits.

Central banks, like all organizations, have some (observed or unobserved) reaction function to geopolitical risk, but given their nature, are particularly central to the phenomenon of gold purchases in relation to geopolitical risk. Here’s The Economist on this question:

But it is another class of investors [than retail investors]—perhaps the most paranoid and conservative of all—that has really driven the recent rally: reserve managers at central banks . . . Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the subsequent freezing of its foreign-currency reserves, was a pivotal moment. It demonstrated to reserve managers that if their country was put under sanctions, American Treasuries and other supposedly safe assets denominated in Western currencies would be of no use.

In fact, OMFIF has put out a fantastic report on this, called Gold and the New World Disorder (OMFIF 2024), which, as its name suggests, discusses the theme at length. Its title pretty well sums it up: the thrust is that geopolitics is a major tailwind for gold, fueling large-scale central bank purchases.

Suffice it to say, central banks have been buying a lot of gold recently by historical standards. And central bank demand matters a fair bit. For context, in 2024, central bank demand accounted for roughly 23%5 of total gold demand. Central banks have generally been net sellers of gold from 1970–2008, only hesitantly re-entering the market on the heels of the Global Financial Crisis. But the pace has picked up a lot since then, with official monetary gold reserves nearing levels not seen since the 1960s. The OMFIF report has a nice visual on this (the World Gold Council is likely talking its book a bit, but still):

Source: OMFIF 2024, p. 7

Source: World Gold Council, 2024 Gold Demand Trends Report

And, consistent with the thesis explored below—that geopolitical risk and macroeconomic uncertainty are key drivers in the central bank purchases—most of the central bank buying in the last year came from countries most exposed to those risks, emerging markets:

Source: World Gold Council, 2024 Gold Demand Trends Report

Moreover, the trend is, according to central banks themselves, set to continue:

Source: World Gold Council, 2024 Central Bank Gold Reserves Survey

Central banks and gold purchases: geopolitics

The OMFIF report suggests that gold’s recent renaissance is attributable to three primary drivers: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, inflation, and American sanctions “weaponizing” the dollar.

Sanctions and the dollar

Perhaps some of the best work on this topic comes from Dr. Daniel McDowell, a sanctions doyen and professor of political science at Syracuse University. Dr. McDowell has written an excellent book on sanctions and de-dollarization, Bucking the Buck (Oxford University Press, 2023, here), which I encourage all my readers to explore, and which I cite heavily here. Dr. McDowell was kind enough to share with me an electronic pre-print of the book and has given his permission to reproduce here some of his charts on this question.

As most of my readers know, sanctions jurisdiction kicks in when one interacts with American institutions subject to American laws barring them from providing services with sanctioned entities (if not, see here). Central banks around the world have reserves in different foreign currencies; a large share (roughly 57.4% as of Q3 2024) are in dollars, and the vast majority of those dollars are in custody (digitally) in lower Manhattan at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Likewise, many foreign central banks’ gold stores (6,331 metric tons) are also held 50 feet below sea level in the New York Fed’s gold vaults (many also reside in the Bank of England’s vaults). As any good prepper or autocrat will tell you, a safe way to keep unfriendly governments away from your wealth is to hold it in gold bars in territory you control and can guard with guns. So, one way to do this if you think you’re going to be targeted by American sanctions is (1) hold gold instead of dollar reserves (because they’d be legally in New York state, subject to US sanctions laws); and (2) hold your gold physically in your own country.6 Hence, gold as a bulwark against sanctions.

I want to pause here to note some macro issues before diving into this. For one, there is a limit on how much monetary gold is out there. Second, this is costly not just in a paying-for-protection sense, but also in a giving-up-interest payments sense (see fn. 6). Third, paying for things in physical gold remains difficult. In many ways, gold is an inferior solution: what central banks concerned about sanctions would prefer is a liquid reserve currency that pays them interest, but free of geopolitical “meddling.” This gets at a crucial Bretton Woods nature-of-money point: there are only so many safe assets out there. Most are US Treasury securities. There is a far second in euro-denominated safe assets, but (1) not many; and (2) also the EU has sanctioned Russia and Iran, and even frozen the Central Bank of Russia’s reserves, so it’s unclear that’s a better option if you’re an autocrat allergic to the Western bloc (or what’s left of it). You are therefore left with not many safe assets, so gold starts to make some sense.

And it does make enough sense to matter. Here are some illustrative excerpts from the OMFIF report (p. 9):

A third well-known central banker, now retired, provides a similar perspective: . . . ‘US led sanctions have had an impact on dollar markets worldwide. I talk to the authorities in many countries and have noticed that central banks – not just the Russians and the Chinese – are speaking increasingly about putting their reserves into other assets rather than the dollar. Gold is one of the alternatives. It is the ultimate source of liquidity. If a third world war broke out, gold could become very useful.’

In extremis, that is all true. Take, for example, the case of Venezuela in 2015, which Dr. McDowell covers in detail in his book (pp. 61–63), in a section entitled “gold reserves as insurance against US sanctions.” In a nutshell, Maduro’s pariah regime saw the geopolitical writing on the wall and in 2011 began to repatriate its physical gold stocks from Europe to Venezuela. After 2015 when US sanctions hit hard, among other things, the central bank of Venezuela successfully moved gold ingots physically (via Russian planes, characteristically) to neutral countries (e.g., Turkey, the UAE) in exchange for physical euro banknotes. Last year, two central banks—the Reserve Bank of India and the Central Bank of Nigeria—disclosed that they repatriated gold reserves from overseas (they did not say that this was about sanctions concerns explicitly).

Dr. McDowell goes on to empirically show that when countries are hit with American sanctions (measured by sanctions-related executive orders, or SREOs), they are more likely to purchase gold:

Source: McDowell 2023, p. 70

Here’s Dr. McDowell on this in detail (pp. 71–72):

To shed further light on the magnitude of the effect of SREO and sanctions risk on gold purchases, Figures 4.7 and 4.8 display the predicted marginal effects. Beginning with the dichotomous sanctions measure (Figure 4.7), the model estimates that countries not under an SREO increased their gold holdings by an average of 2.3 metric tons a year during the study period. By contrast, countries targeted by an SREO increased their gold holdings by an estimated 15.4 tons annually—a difference of more than 13 tons of bullion.

Source: McDowell 2023, pp. 71–72

And this tracks with recent experience broadly of large central bank gold purchases as geopolitical risk has intensified (although there is more to it than sanctions, as we explore below).

Other non-sanctions geopolitical risk

Beyond sanctions, there are other geopolitical reasons you might be interested in gold. For one, Congressional brinksmanship on the debt limit and the threat of an American default means that the risk of holding Treasury (and, to a lesser extent, Agency) securities is higher now than it’s been in the past. Recent gold volatility has also been driven by concerns about tariffs, with American appetite for the yellow stuff soaring on concerns that Mr. Trump would levy a tariff on gold imports (FT):

Concerns that Trump might place tariffs on bullion have driven an unprecedented surge of gold bars into New York, where stockpiles on the Comex have reached record levels. Since Trump was elected, more than $70bn of gold has been flown into New York, although that flow has recently started to slow.

The World Gold Council in its 2024 Gold Demand Trends Report agrees, noting that “armed conflict giving way to global trade and economic conflict may support central bank’s net buying trend.” To boot, the more you hear from the Trump administration about the dollar (e.g., taxes on capital inflows into the US), the more you might start thinking about an alternative.

Central banks and gold purchases: everything else

Of course, there are other reasons that central banks might care about gold.

Even in the absence of sanctions and geopolitical risk, there are reasons countries might want to shift away from holding huge amounts of their reserves in dollars. For one, the US simply represents a smaller share of the world economy than it once did, so it would make some sense to diversify your currency portfolio to broadly reflect that, and if you proxy “the rest of the world” (after dollar, euro, pound, and a few other semi-reserve currencies have been accounted for) with gold, you’d expect to see an upwards trend.

The recent interest-rate hiking cycle has reminded Treasury bondholders that long-duration securities, by definition, carry serious interest rate risk (cough cough, Silicon Valley Bank).

For emerging market central banks, the recent rate-hiking cycle has reminded reserve managers that foreign exchange intervention may be necessary, and gold offers a way to hedge exchange rate risk (at a minimum by putting “money in the window”) without draining dollar reserves needed to pay for imports.

There is also some herd-mentality sense in holding gold. Imagine you’re a central bank not at risk of American sanctions (like a European central bank). So long as you think gold remains in the game as a reserve asset, potentially because you think other central banks will continue buying (perhaps for some of the geopolitical reasons discussed), then it makes some sense to have exposure to it as an asset. Recall that central banks are generally pretty limited in what they can hold as reserves assets. So, if you’re trying to diversify, gold is one of the few asset classes you can gain exposure to. The Czech National Bank is a good case study (OMFIF 2024, p. 19; emphasis added):7

In percentage terms, the most spectacular increase in gold holdings in Europe is being enacted by the Czech National Bank. Aleš Michl, CNB governor, has outlined a policy of raising gold reserves to 100 tonnes, a 10-fold increase compared with the period before the invasion of Ukraine. The Czech Republic has quadrupled gold reserves since then, up to the end-September figure of 46 tonnes, and expects to make further steady purchases in the next three years. According to Michl, the plan is to engineer an increase in gold reserves alongside equities to boost the return on the reserve portfolio and guard against a return to a loss-making position. ‘We need to reduce volatility,’ Michl has said. ‘And for that, we need an asset with zero correlation to stocks, and that asset is gold.’

This can all be summed up as: gold has balance-sheet protection qualities that exceed its geopolitical hedging characteristics.

Revealed preferences

If we really want to know what’s driving central banks to buy so much gold . . . why not just ask them? Well, the World Gold Council did, and the results are pretty interesting:

Source: World Gold Council, 2024 Central Bank Gold Reserves Survey

The de-dollarization figure is striking: over one in three central banks sees value to gold as a de-dollarization vehicle (either highly or somewhat). And note that this is percent of respondents not scaled for reserves holdings. In other words, if, for example China was concerned about sanctions and wants to de-dollarize, that would still show up as 1/57 respondents, even though China’s share of world reserves is very substantial.8 In other words, you don’t need many central banks to care if those central banks’ holdings are really large.

Geopolitics broadly clearly matters. 65% of respondent central banks said that the geopolitical diversification factors of gold influenced their gold reserves decision highly or somewhat. And geopolitics probably matters more than the headline figures would suggest. How? Concerns about geopolitical instability creep into other categories, like default risk (e.g., geopolitical uncertainty in the US), portfolio diversification (e.g., diversifying away from Treasury bonds), and crisis performance (e.g., war, geopolitical instability, etc.).

Another point to make with respect to geopolitics broadly (inclusive of but not limited to sanctions and dollar policy) is that many of the other measures (e.g., liquidity, historical position) don’t really change much over time, whereas geopolitical risk does. In other words, while those factors may matter more, they are also mostly steady state, and thus unlikely to be driving changes in gold policy. At the margin, which is what we care about for looking at changes, geopolitics certainly matters, and is one of the few factors with high volatility.

Conclusion: geopolitics and volatility as tailwinds

There are of course other things going on. Gold demand generally comes from private investors too, both institutional and retail—although that is related to central bank gold purchases through the price mechanism. For example, last year, Wells Fargo estimated that Costco was selling $200 million a month in gold bars (!). There’s some (mostly) unrelated stuff too, like jewelry demand (although gold jewelry has been used in India to evade capital controls, so it’s not perfectly unrelated to geopolitics). And, of course, there’s more to gold prices than demand—mining output and recycling supply obviously matter. All to say, we’ve focused here in a particular angle because it seems particularly important, but there’s a lot going on.

As we’ve seen, gold tends to rise during periods of crisis, perceived or real. Maybe it’s just a canary in the coal mine about the world becoming more volatile (as if we really needed another message about that). We’ve seen an empirically messy picture; but bringing in evidence on geopolitics and central bank gold purchases, we’ve uncovered a persuasive lurking variable: geopolitical factors are pushing central banks to make more gold purchases, providing a strong tailwind to the asset class.

Trevor Greetham of Royal London Asset Management has put it pithily: “gold can act as a geopolitical hedge, an inflation hedge and a dollar hedge.” Maybe it’s an ersatz panacea for all perceived risks, geopolitical, inflationary, trade war-related, or otherwise. While its usefulness as a hedge is almost certainly overblown (see, e.g., the positive correlation between the S&P and gold, or the inverse correlation between CPI inflation and gold in this period), a central tenant in all things financial is a concept that Noah Yuval Harari has identified, which can be roughly paraphrased as: for religion to work, you need to believe in God; for money to work, you just need to believe that other people believe in money.

Note: You can find the code for this analysis for free here.

You can follow me on Twitter (X) @ArnoldVincient, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

This work is independent from and not endorsed by the Yale Program on Financial Stability or Yale University; all views are my own.

Caldara, Dario and Matteo Iacoviello (2022), “Measuring Geopolitical Risk,” American Economic Review, April, 112(4), pp.1194-1225.

Bank for International Settlements, Real Broad Effective Exchange Rate for United States [RBUSBIS], retrieved from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis here.

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Median Consumer Price Index [MEDCPIM158SFRBCLE], retrieved from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis here.

Why then don’t I use central bank gold purchases in the regression? A few reasons. First, I wanted the regression to be somewhat comparable to others typically run in the field (by academics, investors, etc.), which usually look at a variable set similar to the one I have here. Second, monthly central bank gold purchase data in raw data form was tricky to locate. Third, there are some obvious endogeneity/multicollinearity issues here (which also makes the monthly data a little funky—central banks are often buying and selling within the year on the basis of reserves management policies, whereas the aggregate year/years changes are probably more reflective of their policy direction).

From Table 1: (1,044.6 / 4,553.7)*100 = 22.9.

This is not cost-free, mind you. You do have to have, like, an army or goons or an Italian Job-impervious vault or something to protect that gold, which is not cheap (and also gold doesn’t earn interest, so you’re leaving money on the table). Also you might get robbed. Fun history fact: when the US operated the Gold Pool in London and sterling was unstable, the US had to top up the monetary gold stock with physical shipments from the East Coast of the United States, but that involved a US Navy escort—not cheap!

Note, though, that per the regression analysis, gold—at least some proxies of it—doesn’t necessarily have zero correlation with equities, although of course that relationship changes over time.

Although the precise number is more difficult to pin down than it might seem, since many of China’s reserves are in “shadow reserves” in state-owned policy banks and sovereign wealth fund-style vehicles.