Dispatch No. 4

A roundup of learnings

N.b.: I’m adding markers for older pieces and will do so also for paywalled pieces in the future.

Fiscal Dominance: A Primer. Stephen Cecchetti and Kermit Schoenholtz. Money and Banking.

Fiscal dominance is hot again (turns out it’s a very cyclical thing in the thousands of years of human existence). Cecchetti and Schoenholtz are the right minds to bring to bear on this topic. First of all, starting a piece with a juxtaposition of quotes from Thomas Sargent and Neil Wallace on the one hand, and a Truth Social post from Donald J. Trump on the other is (1) funny, and (2) brutal. 10/10 on a great opening.

But this is a sober piece. Embedded in those quotes is that the US is at serious risk of fiscal dominance occurring. Perhaps one of the best contributions of this note is to define, clearly, what fiscal dominance is and how it’s different from monetary dominance. Here’s their definition: “when fiscal policy pressures or compels a central bank to forsake its price stability objective in favor of helping to finance the public debt.” There’s some nuance here in my view: interventions in public sovereign debt markets might justifiably be for market functioning purposes, not backdoor fiscal support. But the line is blurry.

Importantly they tie in sovereign debt, which Americans often don’t think about (my emphasis):

… the central bank faces a tradeoff between satisfying fiscal needs and keeping prices stable. For example, to ease their financing burden, fiscal policymakers may pressure the central bank to lower the policy rate below the level consistent with its inflation target. Fiscal policymakers would benefit in the short run both from the lower cost of new debt issuance and from a surprise inflation that lowers the real value of outstanding debt – analogous to a partial default. Eventually, however, lower interest rates drive inflation expectations, and then inflation, markedly higher, leading to a loss of central bank credibility.

For those who enjoy financial history, there are lots of great Easter eggs, but as the authors point out, you don’t need to dust off history books to see fiscal dominance: Venezuela, Argentina, and Türkiye have had episodes very recently. And they make the point that the US is pretty exposed today, from a standpoint of debt service sensitivity to interest rates: “a sustained one-percentage-point rise in the average yield now adds over one percent of GDP to the annual cost of federal finance: that is more than double what an equal yield increase added in the mid-1980s.” This is not hypothetical with the sitting US president pressuring the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates explicitly to lower the country’s debt servicing costs.

Tariffs, Stablecoins, and the Demand for Dollars. Anantha Divakaruni and Peter Zimmerman. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

More on stablecoins. This is a recent paper (from August) that uses dollar stablecoin trading as a proxy for dollar trading writ large and analyses how those trading patterns respond to tariff announcements. For those who aren’t FX market plumbers, the core challenge is that most FX trading is over-the-counter (OTC), meaning it’s done bilaterally or trilaterally through dealers, instead of on exchanges. This makes getting disaggregated high-frequency data on FX trading difficult—trust me, I’ve tried.

One way to square this circle is to use market-based trading (enter: stablecoins) as a proxy for broader dollar trading. Now, there are some challenges here, because people trade dollar stablecoins for reasons other than those for which they might trade plain-vanilla FX, but it turns out it’s not a bad proxy (they do some robustness checks for those interested). Specifically, they use limit order book imbalances, which in English means the relative share of orders placed by buyers versus sellers. And they can do geographic identification by proxy of currency used (e.g., folks buying USDC in Turkish lira probably are Turkish—fair enough).

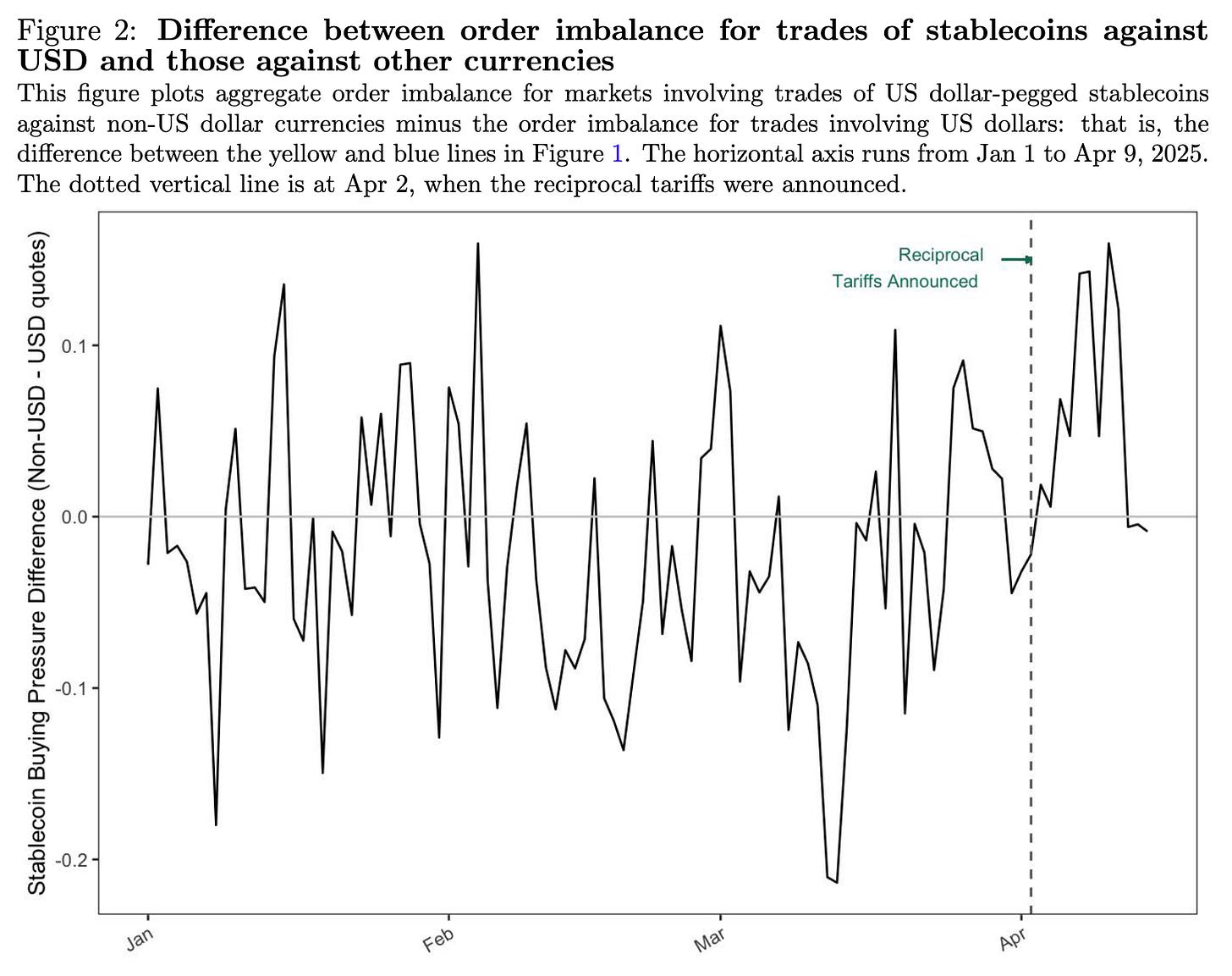

Their findings suggest that in response to “liberation day" tariff announcements, there was increased demand for buying dollars (via stablecoins):

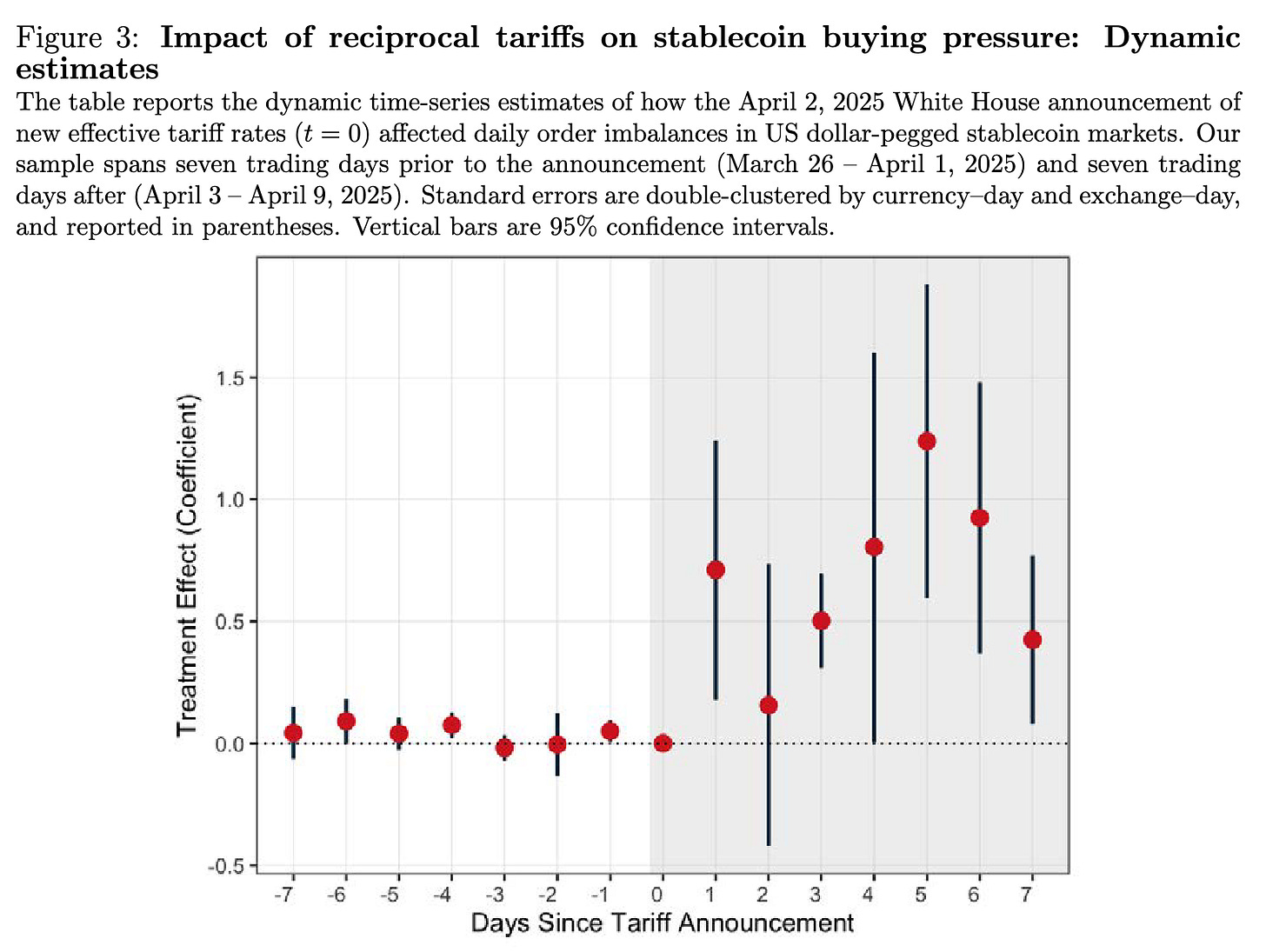

But they can do one better! They then look at differences in announced tariff rates across countries to quantify by how much the tariff rate affected dollar buying (again, as proxied by dollar stablecoin trading). To do so, they run a fixed effects regression model and obtain the following results (my emphasis): “In all five models, we find that a larger increase in the tariff rate on a country is associated with significantly higher buying pressure of dollar-pegged stablecoins with respect to that country’s currency.”

These findings may seem esoteric, but they’re actually pretty important insofar as they relate to the reserve-status-of-the-dollar debate. During the GFC, which, as astute foreign observers oft point out, was caused by the US, the dollar appreciated and there was increased demand for buying and holding dollars, very counterintuitively. This is because of the safe haven status of the dollar, as expressed in the dollar smile theory. These recent stablecoin proxy results show that, even in the face of tariffs from the United States, foreigners tend to buy more dollars in response.

TINA: There Is No Alternative (yet).

Financial Channel Implications of a Weaker Dollar for Emerging Market Economies. Mikael Juselius, Philip Wooldridge, and Dora Xia. BIS.

Speaking of the dollar abroad, the BIS has a nice piece out on dollar depreciation in EMs. Here’s a thought for EMs: trade uncertainty and tariffs = bad, depreciating dollar = good, so it’s all fine? Maybe.

But exactly how depreciating dollar = good is not completely simple, and not universally true. A few channels, the authors say:

The balance sheet channel: If your balance sheet has local currency assets and (unhedged) dollar liabilities, dollar depreciation mechanically strengthens your balance sheet by reducing liabilities.

The financial channel of the exchange rate: For global banks, the improved strength of those borrower balance sheets (see above point) means you can expand credit; this channel is supportive for goods trade, among other things.

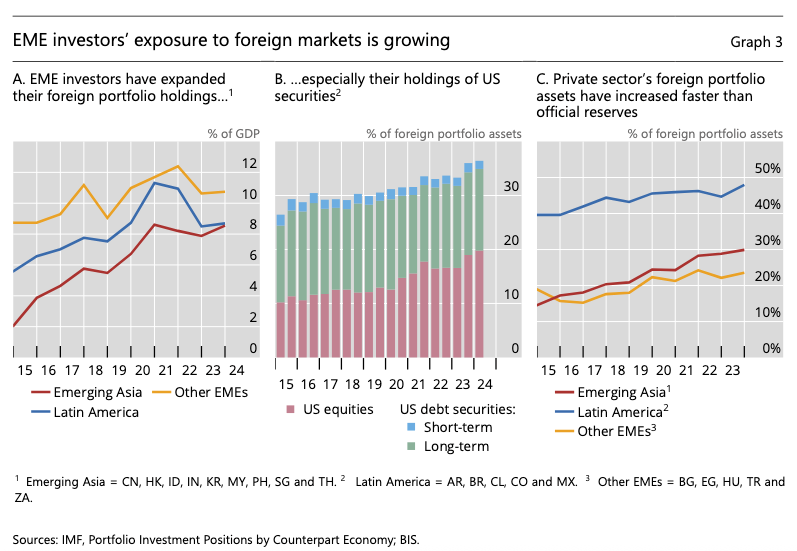

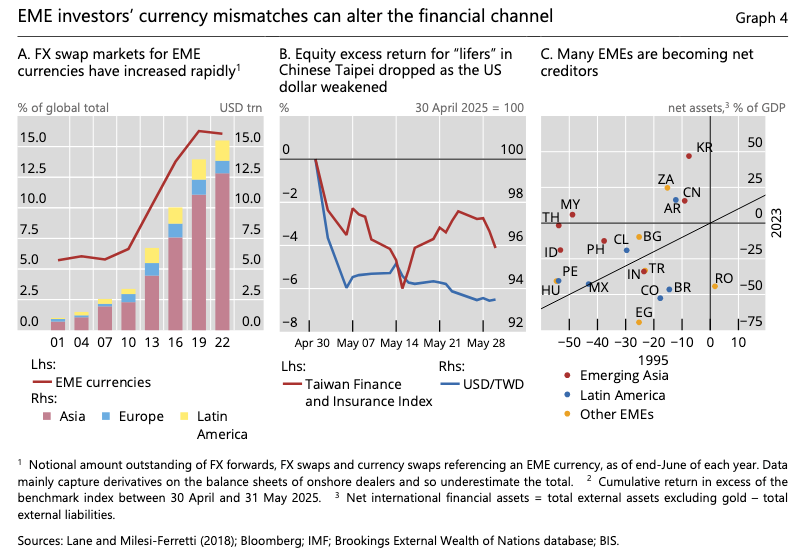

The other balance sheet channel: So, the above could be inverted: if an EM company/bank has local currency liabilities, but dollar assets, then actually dollar depreciation would result mechanically in losses. We haven’t historically fretted about this, because traditionally EMs have been more likely debtors and the US has been a creditor, but that is increasingly not the case:

Of late, EMs have increasingly taken on creditor positions, particularly vis-à-vis the United States. This means more dollar-denominated assets on their balance sheets, which means losses on dollar depreciation. To be sure, that’s not to say all or most EMs are net creditors to the US or the rest of the world, but on the margin, they have more long-dollar positions than they used to in aggregate, which attenuates the tailwinds of dollar depreciation.

Of course, if these positions are hedged, then they are less exposed (a 100% hedged dollar position is synthetically a non-dollar position). If you want to see a case study of this, look to Taiwan, the authors say, where large unhedged long dollar positions on the balance sheets of life insurance firms expressed themselves in losses, which materialized in equity prices for those firms. And this matters increasingly because while not all EMs are net creditors, many are, and more are becoming so:

This all implies that the financial channel of the exchange rate might ultimately start working in the other direction: losses on balance sheets resulting in credit supply contraction, not expansion.

Can China’s Long-Term Growth Rate Exceed 2–3 Percent? Michael Pettis. Carnegie Endowment. (🕐)

I read Michael Pettis’ 2023 prediction/analysis on China’s growth, and thought it was worth re-upping.

Some background context for the non-China-watchers: the number one keyword when reading about China’s macroeconomic outlook is imbalance. This refers to the idea that China’s economy is unusually reliant on investment for growth relative to consumption (and, to a much lesser degree, net exports). For reference, for many advanced economies, investment’s share of GDP hovers around 15–20%; in many developing countries it’s as high as 30–35%; in China (in 2023) it was ~43%. As returns to investment start to decline (diminishing marginal returns are everywhere!), every new unit of investment yields less growth. (If this doesn’t make sense, read this footnote.1) This is straightforwardly a challenge, one that policymakers in China themselves recognize.

Pettis argues that this eventual rebalancing isn’t a policy option, but that it must happen/will eventually be forced because of China’s rapidly growing debt stock, which he argues is the other side of the investment coin. There are, then, two ways to get around this problem: (1) do less investment, or (2) increase the rate of return on investment. Pettis thinks the latter is highly unlikely. So, how can China rebalance?

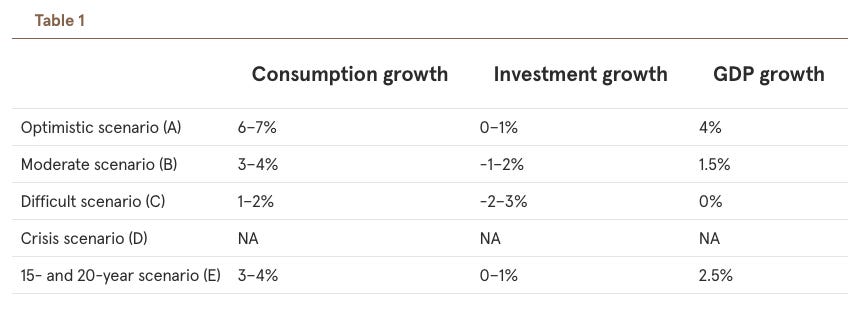

Pettis says, essentially: with considerable difficulty. He draws out five plausible scenarios for China to get its investment share of GDP to ~30% in ten years:

Surge in Consumption: To get this done in ten years, consumption needs to grow by 6–7% a year while investment grows 0–1% a year.

Current Consumption Rates Hold Steady: Then GDP growth needs to slow considerably. To get it done in ten years, investment needs to contract at negative 1–2% a year, and GDP hovers around 1.5% growth per year.

Sharp Decline in Consumption Growth: GDP growth remains flat and investment would need to decline in the area of 3% a year (although net exports would surge, which would help).

Sharp GDP Contraction: So unlikely he doesn’t even model it.

Rebalance Over an Extended Period: If China takes 15 or 20 years to achieve the rebalancing with consumption growth at 3–4% a year, then GDP growth drops to 2% and 2.5%, respectively.

He summarizes the potential outcomes in a tidy table for us:

Here’s a key bit of his bearish takeaway:

Unless Beijing can somehow manage to set off a surge in consumption growth, which is possible but highly unlikely, it will be very difficult for a rebalancing China to grow at rates much higher than 2 percent . . . China can slow down the adjustment pace to one that is more politically acceptable, but this involves two costs. The first is that a longer period in which debt continues to rise faster than the country’s debt-servicing capacity increases the risk of a disruptive financial adjustment. The second is that, like with Japan, slower growth stretches out over a much longer time period. It is worth noting that in the early 1990s, Japan’s share of global GDP was close to 18 percent. Within twenty years, it was less than 8 percent.

Well, on that bright note, that’s a wrap.

When you’re a poor country, building things like roads, bridges, ports, and highways yields a lot of return: you couldn’t move people and goods around the country/world, now you can. If you’re a rich country, then you’re probably at the maximum capacity of infrastructure you need to run an economy, or close to it. Of course, there will always be new investment to be made (e.g., 5G, AI data centers, etc.), but as a relative share of your whole economy, it’s a lot smaller than when your country was much poorer. But, your citizens are richer and consume a lot more, so this drives a lot of your growth. For reference, US consumption share of GDP is roughly 68%.