Eurodollar Stablecoins, Bills, and Monetary-Fiscal Entanglement: Part I

On the history of monetary-fiscal arrangements in America

This is the first in a three-part series of essays exploring stablecoins and monetary-fiscal entanglement.

A lot has changed since we last talked about stablecoins here! Namely, the GENIUS Act has passed, bringing stablecoins fully into the regulatory fold, and thereby providing the imprimatur of regulation needed to bring financial products into the mainstream. There’s a lot one could say about stablecoins, but I want to think here about how they might act as another innovation in financial infrastructure that increases the capacity of the market to digest ever-expanding amounts of debt.

A survey of American financial history shows that the government has made use of the monetary system (monetary authority as well as market structure) to help monetize fiscal debt in ways that support high issuance volumes, usually in times of war, but sometimes not. Today, stablecoins offer a potential new monetary-fiscal arrangement, one in which latent demand for American sovereign debt is tapped in foreign retail investors (foreign institutional investors have long been tapped to help fund American deficits). While the outcome is far from certain, if stablecoins do open a path to new demand for American debt, it will have far-reaching implications for soft power, the international monetary system, America’s fiscal deficit, and monetary policy.

On monetary-fiscal entanglement in American history

“The line between money and the public debt has never been entirely clear or distinct.” — Menand and Younger (2023, 237)

To understand the future of monetary-fiscal entanglements, we need first to understand their past. I’m using the term “entanglement” (or “arrangement”) intentionally—as opposed to something like “monetary financing” or “fiscal dominance”—because, as we’ll see, the role of money markets and their infrastructure in the US has not always been characterized by fiscal dominance or the like, but it’s always been intimately tied to the issuance of fiscal debt (safe assets).1 The source for a readable history here is Menand and Younger 2023, which lays out four ‘fiscal-monetary configurations,’ summarized below:

The National Banking System: 1863–1916

Prior to the National Banking System, the US nominally separated fiscal funding from money markets,2 but this broke down when the financing requirements of the Civil War pushed the United States (and the Confederate States, incidentally) to monetize debt issuance. In 1862, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, which allowed the Treasury to mint paper money (which was green, hence “greenbacks”) to fund the war effort, but this resulted (predictably) in inflation. As a result, they changed tact: in 1864, Congress passed the National Banking Act, which essentially forced state banks to obtain federal charters. These banks would issue “national bank notes” receivable for payments to the US government, but they had to be backed by Treasury securities: The Treasury deputized the national banking system to buy and indirectly monetize (via issuing notes against them) the wartime fiscal debt. Maturity transformation in support of a war effort, more or less.

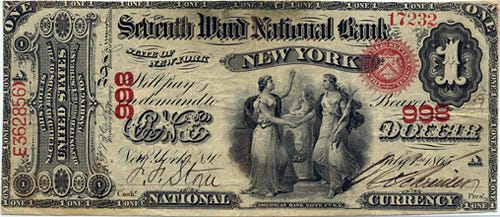

A national bank note; Museum of American Finance

The Federal Reserve System: 1916–1951

By 1913, the Federal Reserve System had been created and the primary money instrument of banks had shifted from notes (the paper form of deposits, if you will) to deposit accounts on which checks could be written (“checking” accounts). The new Federal Reserve banks could buy Treasuries directly. A few months after the Federal Reserve System was founded in 1913, though, war broke out on the Continent, and massive financing needs struck again. While the Treasury at first rallied the American populace by marketing war bonds as a patriotic duty, the voluntary fundraising proved insufficient. So, the Treasury deputized the Federal Reserve to help fund the war by use of credit controls and bridge financing for war bonds. By World War II, the Fed intervened to support war finance more strongly, and in spring 1942 agreed to control all borrowing costs of the US government, capping short-term rates at 0.375% and long-term rates at 2.5%. At this point, the majority of war debt was financed by expanding the money supply, in part via direct Fed purchases, and in part via commercial bank deposit expansion funding purchases of government bills.

The Primary Dealer System: 1951–2008

1951 marked the famous Fed-Treasury Accord, wherein the Fed gained its political independence, in part because of the crowding out of bank lending, and in part because of the need to control inflation that arose at the end of the war and the outbreak of hostilities in Korea. The Accord meant the Fed would stop its yield curve control, and the Treasury would focus on smooth, predictable, and affordable debt issuance. A less-remembered episode in the 1950s was soon to follow, though, when Treasury market disruption struck in the spring of 1953, triggering the SOMA manager to alert the FOMC that there was, “virtually no market for government securities at the present time” (FOMC meeting minutes). The Fed intervened at first with restraint (via repo) and then more intensely with outright purchases. This episode exposed to the Fed that Treasury securities dealers couldn’t stand on their own yet, and thus the Fed decided to support the market by financing the trading inventories of nonbank dealer firms via repo.3 The legality of this practice was internally questioned, but ultimately the Fed’s legal counsel determined it was permissible on the basis that the repos were supportive of market functioning, not aimed at helping particular firms. The Fed’s implicit funding backstop engendered the growth of a commercial market for repo to dealer firms. To become a dealer able to participate in direct Fed operations (a primary dealer), dealer firms needed to participate in (i.e., underwrite) Treasury auctions. In essence, the Fed was indirectly supporting the digestion of fiscal debt via backstopping and subsidizing the dealer firms that sold the debt.

The Shadow Dealing System: 2008–2022

By 2008, the conversion of many non-bank dealers into bank holding companies or their subsidiaries introduced new prudential regulations which limited intermediation activity in formerly non-bank dealers (e.g., market risk capital rules and leverage ratios). Other regulations later added to the cost of capital for intermediation activity, which crept away from the traditional banking sector and into the “shadow dealing” sector (mostly principal trading firms and high frequency traders, often hedge funds). These funds began to accumulate long positions in Treasuries and short positions in their derivatives, thus looking like a synthetic version of older dealer balance sheets. However, this approach involved leverage, making the system more brittle, which ultimately showed in the 2014 “flash rally” and the 2020 Treasury market panic. Like before, the Fed needed to support this crucial market and, after first intervening with repo expansion, ultimately took to large-scale asset purchases, this time for financial stability and market functioning reasons, rather than monetary policy.

Upshot

Over time, we’ve seen that the US government, like other governments throughout the world (check out Sweden!), taps all demand available to absorb its debt, with money claims having an obvious appeal (because short-term rates tend to be lower than long-term rates). Whether via the creation of new paper bills, national bank notes, or central bank purchases or interventions, the monetary plumbing has always been intimately tied with the production of safe assets, itself a byproduct of fiscal debt. Contrary to popular belief (e.g., gold bugs), this system has been remarkably resilient and has adapted to the changing landscape of the financial system over time, while naturally finding the cheapest and most efficient ways to finance government deficits and supporting dynamic credit creation. (The elasticity of the currency is a feature, not a bug!)

Do stablecoins represent the next chapter in monetary-fiscal arrangements? Maybe, but unlikely to mirror the scale and importance of previous innovations. For there to be a new monetary-fiscal arrangement, the government would need to find new demand for its debt. The qualifier new is doing heavy lifting there. From here, we’ll need to figure out whether or not stablecoins can actually unlock latent net new Treasury bill demand. That’s where we’ll go in Part II.

This series has benefitted from generous comments from Rashad Ahmed and Richard Berner, and from fruitful discussion and research-sharing with Elliot Hentov and Steve Englander. All mistakes and views are my own, but I want to thank these brilliant people for sharing their time.

This is because money markets (money market funds, repo, etc.) need to be backed with essentially risk-free assets (i.e., sovereign debt). This is not to say that US government debt is truly risk-free—of course, there is risk of default (arguably when the US de-pegged from gold in 1933); inflation; and interest rate risk. But for our purposes, we’ll call government debt the risk-free asset, since ultimately the government has the unique ability to tax and seize to back its debt.

Notably, though, while the Republic was young, money and sovereign debt were not, and Alexander Hamilton, the father of American finance, was keenly aware of the convertibility between sovereign debt and money. He was the architect of the First Bank of the United States, America’s first central bank, which could issue notes that were receivable for payment to the US government.

Given that this involved non-banks, the Fed could have invoked Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act (FRA), but the circumstances of subsidizing dealer inventory were neither unusual nor exigent, so the Fed invoked FRA Section 14, allowing it to purchase and sell securities (since this was repo, the Fed was purchasing and re-selling) on the open market. In fact, the Fed first used its Section 14 authority with non-bank dealers in 1920 to smooth likely market dysfunction surrounding a maturity wall of World War I bonds, which was legally controversial at the time. See Menand and Younger, 276-277, fn. 215.