Eurodollar Stablecoins, Bills, and Monetary-Fiscal Entanglement: Part II

Can stablecoins unlock latent demand for Treasury securities?

To recap, in Part I we discussed the history of monetary-fiscal arrangements in the United States, from the free banking of the 19th century to the primary dealer infrastructure of today. We learned that in the past, financial plumbing innovations have unlocked new sources of latent demand1 for Treasuries, but there’s an argument to be made that stablecoins (which here refers to dollar stablecoins) might just reshuffle existing demand for Treasuries. So, we were left with a puzzle: for stablecoins to facilitate any kind of monetary-fiscal arrangement, they’d need to unlock net new demand for T-bills. Do they?

There are reasons to be skeptical. As Stefan Jacewitz of the Kansas City Fed argues, people have to buy stablecoins with something, which is usually bank deposits, but could be money market funds, in which case the effects on net new Treasury demand would be attenuated. However, this analysis and many others mostly focus on the domestic system.

Here’s my pitch: stablecoin circulation in the United States (onshore) will mostly (though not exclusively) reshuffle existing demand, but stablecoin circulation outside the United States (offshore) will create genuinely new demand. Further, that’s where most of the growth will be, so the offshore segment should not be overlooked.

How do stablecoins impact T bill demand?

State Street puts this very well (bolding original; italics my emphasis):

There are four primary channels through which stablecoin demand can manifest itself:

1. Displacement of bank deposits: Primarily involves asset substitution, resulting in minimal net-new demand as bank reserves and associated short-term assets on the bank side are simply transferred to stablecoin reserves without any system-wide increase in demand for T-bills.

2. Substitution of Money Market Funds (MMFs): Like bank deposits, this represents an asset swap wherein stablecoins are substituted for MMFs, limiting additional net Treasury demand. We view this as a low-probability scenario as stablecoins cannot pay interest, whereas MMFs do.

3. Foreign deposits converted into stablecoins: This channel represents a genuine net-new Treasury demand, as global investors shift funds from foreign assets into stablecoins backed by Treasuries. Liquidity preferences rather than yield-seeking behavior appear to be the primary driver of this shift, given that stablecoins do not pay interest.

4. Cash and banknotes replaced by stablecoins: Direct conversion of physical currency into stablecoins could generate new, incremental T-bill demand as issuers seek stable collateral backing. We see this as a low-probability scenario in most economies.

Of these channels, only foreign deposit conversion and cash/banknote replacement produce substantial new demand, while displacement from bank deposits and MMFs largely reflects asset reallocation rather than net-new demand.

Agreed! Mostly. One bone to pick: I disagree on the first bit: no system-wide increase in demand for T-bills as a result of bank deposit migration to stablecoins. The reality is that banks own precious few T-bills (only roughly 8% assets in Treasury securities writ large), where stablecoins own a lot of them. As such, a migration from bank deposits to stablecoins likely would result in a material increase in demand for T-bills (this is essentially like migrating to a narrow-bank model).

Here’s a nice figure they have:

Let’s dive into those two net-new-demand-creating categories.

Cash and foreign deposit migration: how do they create new T bill demand?

There are three ways foreign demand reaches stablecoins: (1) from non-dollar holdings (e.g., I spend my lira and buy USDT); (2) from dollar cash abroad; and (3) from Eurodollar deposits (dollar deposits held offshore—outside the United States).

The first is straightforwardly new T bill demand, as State Street highlights, so I won’t cover it separately here: it is a non-dollar claim becoming a dollar claim backed in large part by T bills, so is mechanically net new T bill demand. This is probably the single largest driver of stablecoin growth—good news for our thesis. But how it creates new T bill demand is clear.

Insofar as net new T bill demand is concerned, though, one might quibble about the latter two: they are both cases of one dollar claim migrating to another, so could we be running into the same mere-reshuffling issue again? No; we have reason to think these migrations too will create net new T bill demand:

Cash

Cash isn’t directly backed with T bills. Directly. Cash—currency—is a liability of the Federal Reserve, and sits on the liability side of the Federal Reserve System’s consolidated balance sheet. On the asset side, the Fed holds lots of things, but mostly Treasury securities and MBS. The Fed could back all its liabilities with short-duration assets and do perfect maturity matching, but it currently doesn’t (intentionally). In any case, the composition of the Fed’s balance sheet is variable, and while the weighted average maturity of the portfolio is declining, it’s certainly not a $1 cash = $1 T-bill money market fund. In fact, according to the Fed’s Sep. 25, 2025 H.4.1 release, T bills account for roughly 3% of the System’s consolidated assets, while cash represents 36% of its consolidated liabilities.2 This is compared to roughly 65% T bill composition behind Tether’s USDT, per its reserves report. So, in a crude oversimplification, if someone migrates $100 of offshore cash holdings into $100 of newly minted USDT, we’d expect roughly $62 of T-bill purchases from this transaction in the system as a whole. That overstates the effect,3 but the direction is clear.

Eurodollar bank deposits

Eurodollar bank deposits are a large market, but they are bank deposits, so mostly backed by loans, not Treasury securities, and certainly not short-term Treasury securities. So, migration out of a Eurodollar bank deposit and into a stablecoin would represent a net increase in T-bill demand. Same as for domestic bank deposit-to-stablecoin migration, as discussed earlier, but likely to a great extent.

The assets of Eurodollar banks are tricky to parse, and there’s no great consolidated location for reporting (in contrast to the onshore dollar banking system). But we can take an illustrative example. The Bank of the Philippine Islands is a bank (in the Philippine islands, shocker) that offers dollar-denominated savings accounts. If you take a look at their balance sheet, government securities writ large comprise roughly 17% of their assets, and remember that’s all government securities, not specifically T-bills, or even dollar-denominated assets; presumably they mostly hold peso-denominated Filipino sovereign debt. Now, again, similar to the Fed’s balance sheet, the bank probably does more exact liability matching, and it’s hard to tell exactly “what they buy” with $1 of dollar liabilities. Suffice it to say, though, even American banks hold well under 23% of assets (probably under 10%)4 in T-bills, so it’s safe to say that Eurodollar banks hold even less. If we assume—very conservatively—that our Filipino bank holds 20% of its total government securities in US T-bills, that’s 3.4% of total assets. But we don’t need exact figures to know that the weighted-average Eurodollar bank T-bill asset composition is far less than USDT’s 65%.

This is no surprise: $1 of a bank deposit is mostly backed by bank asset stuff (e.g., loans, mostly, some MBS); $1 of a money market fund (cough cough, stablecoins) is mostly backed with short-term government securities. We know this. It should be no surprise that the same is true offshore.

Total effect

Yes, it is true that not all offshore dollar stablecoin circulation will reflect net new dollar claims, since some fraction of it will be migrated from offshore dollar cash holdings and offshore dollar bank account holdings. But, given the asset composition backing those claims, we’ve concluded that:

cash → stablecoins = increased T-bill demand

Eurodollar bank deposits → stablecoins = increased T-bill demand

One of two things is happening when dollar stablecoins circulate offshore! Either (1) they are net new dollar claims, in which case, definitely new T-bill demand; or (2) they are migrated dollar claims from cash and Eurodollar bank deposits, in which case, still net new T-bill demand (albeit less on the margin).

Fine, but why would foreigners want dollar stablecoins?

And this question implicitly has an addendum: “, when you could get dollar cash or bank deposits.” That’s the rub, though—those options both have serious drawbacks.

Start with cash. Getting cash offshore is not always easy; there is a limited supply of it (literally, and also because of capital controls); you can lose it/it can get stolen; you can’t earn any interest on it;5 you can’t make cross-border (or even cross-country) payments with it; and it has a limited physical lifespan as it naturally wears down.

In the case of Eurodollar bank deposits, they simply aren’t available to many people, especially in emerging/frontier markets; they often come with heavy paperwork that many people can’t/won’t deal with; they’re not very accessible to people in rural underdeveloped areas, where smartphone apps are the easiest way to access financial services; they often come with fees; and they don’t enjoy FDIC deposit insurance and are not backed one-to-one with other money claims, so there is genuine risk in holding them relative to cash or money fund-style instruments.

And then there’s the general question, addendum aside, of why a foreigner would want to hold dollars at all, in any form. But that’s well-trodden ground: for the same reason that they might want to hold gold or some other perceived safe asset—safety and inflation shelter, plus maybe the benefit of cross-border payments/remittances, depending on the payment rails. And here, stablecoins have some advantages: they can easily be obtained via smartphone, payments are fast and efficient, and they offer a nearly instant off-ramp from the volatility and inflation of local currencies. Eye-popping stylized fact: 43% of sub-Saharan African transaction volume is in stablecoins. The proof is in the pudding.

How big really is offshore stablecoin growth?

Well, okay, I’ve privately heard a stablecoin representative once say, more or less, “our path to huge growth at this point is overseas.” So, the direction of travel is clear. But it’s already big.

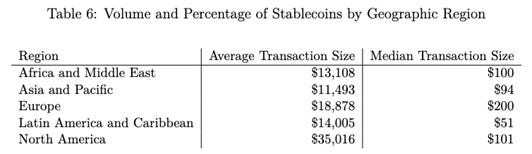

Unfortunately, though, getting exact figures is tough, since stablecoin ownership is pseudonymous by construction and stablecoin companies jealously guard user data. That said, some laudable attempts have been made, notably by Marco Reuter at the IMF. In his paper, Reuter deploys a large language model to exploit natural language and cultural references in stablecoin wallets, as well as transaction data mapped onto time zones, in order categorize them by region of the globe. Using these data, he’s able to map stablecoin flows geographically in a manner that is considerably more robust than the existing commercial databases, which don’t account for virtual private network (VPN) use, which masks the country of origin.6 His finds are telling: 80% of stablecoin wallets are outside of North America, and 72% of transaction volume7 occurs outside of North America. Now, an immediate response to this is, “well, sure, but they’re all wallets with $20 in them doing tiny transactions frequently, that doesn’t mean the share of actual holdings offshore is large.” And that’s fair! It is true that the median transaction size in North America is large, and the mean North American transaction is even larger. But not by a ton. From Reuter:

And it’s also true that these are flow volumes, not stock, so $1 moved across borders 1,000 times becomes a sizable transaction volume, even when the stock amount is tiny. If that were true, though, we should see much lower median transaction sizes, which we don’t see (Africa is virtually the same as North America). As such, it’s reasonable to infer stocks from flows here, as a ballpark estimate, and say with relatively high confidence that 70–80% of dollar-denominated stablecoins are circulating offshore, consistent with (1) eight of ten wallets residing outside of North America; (2) roughly similar transaction sizes inside and outside North America; and (3) 80% of stablecoin transactions occurring outside the United States.

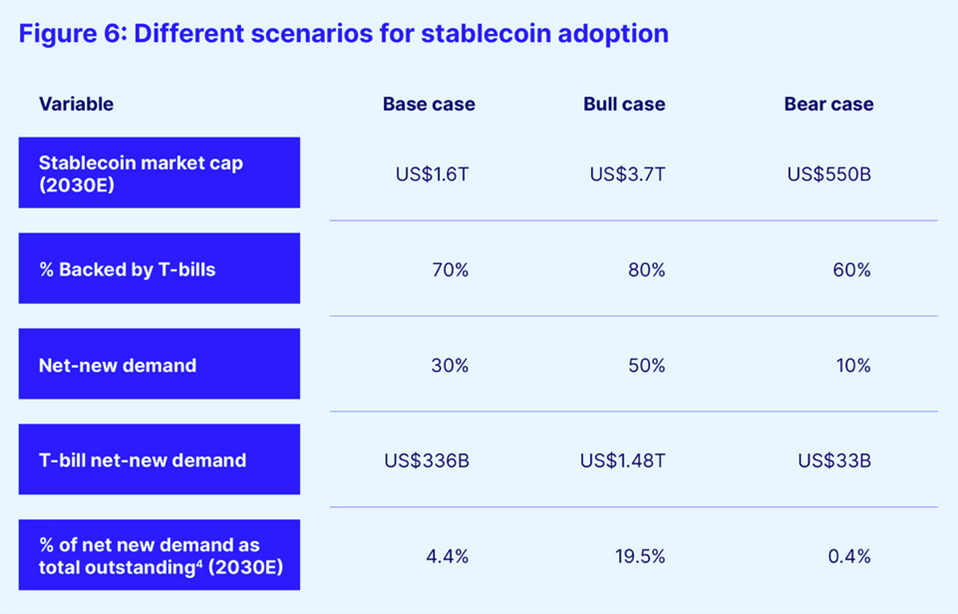

Finger in the wind

Time for some back-of-the-envelope figures. If the stablecoin market reaches $2 trillion in 2028 as TBAC suggests it might, that’s $1.6 trillion of dollar claims outside the US at 80% foreign composition. Of that $1.6 trillion, if we take Tether as a benchmark, we could expect roughly 65% of that to be backed by T-bills, roughly $1.04 trillion. Incidentally, this figure—$1.04 trillion—while for 2028, happens to be almost exactly the 2030 figure Brookings comes up with using conservative estimates of 3% p.a. offshore dollar demand growth and a low 6% stablecoin penetration rate. (Their middle-of-the-road figure is $1.9 trillion.) We’ll talk more about this in the next essay but, suffice it to say, this figure is relatively moderate, if not conservative.

If T-bill supply stays in the roughly 20% of GDP range as it has in recent years, and we take the CBO’s current growth forecasts at face value, then the ballpark 2028 T-bill supply is around $7.6 trillion. If we think that supply would be met at equilibrium with existing buyers,8 then that’s an extra $1.04 trillion on the sidelines (roughly 14% of supply), which should put downward pressure on yields, edge out other market participants, or some combination of both.

Recall that this completely sets aside onshore stablecoins—this is only an estimate of offshore stablecoin circulation, for which we can have higher confidence about net new T-bill demand.

Why should we care about stablecoins specifically, though?

At this point, the crypto-skeptics might be saying, “sure, but this is just a bad money market fund. Bad because it doesn’t pay interest, and a money market fund because it’s . . . a money market fund.” I am deeply sympathetic to this view. Especially in a world of tokenized (actual) money market funds (e.g., BlackRock’s BUIDL or Franklin Templeton’s Benji), it’s unclear how or why stablecoins would exist and grow, offshore or onshore, aside from their original use case as a crypto off-ramp.

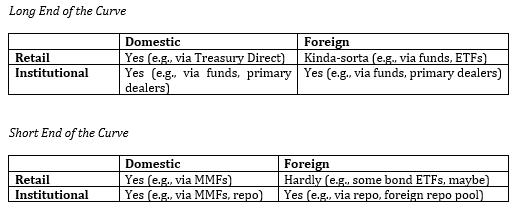

For our purposes here, though, the distinction between a tokenized MMF and a stablecoin9 doesn’t much matter; what matters is that they are tokenized, backed in large part with T-bills, and available to foreign retail investors.

Conceptually (and reductively), you might think about it this way:

Stablecoins (and/or tokenized MMF shares) open up the upper-right quadrant of the second box; that’s basically the innovation here.

Conclusions

In Parts I and II, we have concluded:

Historically, monetary-fiscal arrangements change over time, often leveraging money demand for debt finance;

While purely onshore stablecoins might represent a reshuffling of Treasury demand, offshore stablecoins (Eurodollar stablecoins) represent real net new demand for Treasury securities, but we don’t know yet how much;

Subject to the above, we have a sense that it’s significant, and it is definitely growing;

Ergo, there exists some new T-bill demand and a means to satisfy it via stablecoins, all while shifting the weighted-average maturity of US sovereign debt shorter.

In Part III, we’ll discuss what it might look like if this occurs.

This series has benefitted from generous comments from Rashad Ahmed and Richard Berner, and from fruitful discussion and research-sharing with Elliot Hentov and Steve Englander. All mistakes and views are my own, but I want to thank these brilliant people for sharing their time.

Okay, fine, or created new demand by forcing it via regulation.

Again, the Fed is explicitly not doing asset-liability maturity matching, very intentionally (although is slowly unwinding that via QT). One way to think about the Fed’s balance sheet post-QE is that it’s doing maturity transformation like a traditional bank: you put in $1 of cash (a demand liability), but it’s backed mostly by longer-maturity assets. This is the whole point of QE.

Because the assumption in footnote 2 will be relaxed in reality: the share of T-bills “backing cash” is almost certainly higher than 2.9%, but it’s hard to say since assets are fungible. It is also not in general equilibrium: moving out of cash and into other forms of money might have some effects on bank profits, velocity of money, etc., which are hard to know.

This is based on the aggregated Quarterly Banking Profile (p. 9) data from Q2 2025 released by the FDIC, showing that 22.7% of American banking system assets are Treasury securities. Of those, we can presume only a relatively small fraction is T-bills (back of the envelope, T-bills are meant to be ~20% of outstanding Treasury issuance, so 0.2 * 22.7 = 4.5% of total assets).

Technically, you can’t earn yield on your stablecoins either, but we’ll see that there are existing work-arounds to that (see, e.g., Klein 2025).

He highlights that this is a particularly thorny issue in China, for which the flows from a dataset that doesn’t control for VPNs and his dataset are significant. This is probably not a huge surprise, given that VPNs in China are used to break the great firewall with regularity.

pp. 21–22.

Importantly these existing buyers need not all be domestic, they just need to be non-stablecoins, for this analysis to make sense.

It’s probably too soon to think about, but tokenized securities in general is another option that would also substitute here. For example, direct (fractional) ownership of a Treasury bill might be possible if it’s tokenized. Efforts are underway here. One thing that would be different and affect our analysis would be tokenized bank deposits, which would have (1) a different asset composition and (2) differential impacts depending on whether they’re tokenized US bank deposits or tokenized Eurodollar bank deposits.