Geopolitical Fragmentation, Trade, and Financial Flows

The Fed has found (another) cool gravity model

Researchers at the Federal Reserve Board—Florencia S. Airaudo, François de Soyres, Keith Richards, and Ana Maria Santacreu—have recently published a very interesting research note, entitled Fragmentation? Revisiting the Ideal Point Distance measure of geopolitical distance.

This research comes at just the right time. As geopolitical winds are changing, it is a good time to ask: how might a reshuffling of the geopolitical pack affect trade and financial flows?

Recap: gravity models for days

For those who have studied international trade economics, gravity models will be very familiar. For those who haven’t, here’s the TL;DR:

A fun thing about international trade between countries—almost philosophically cool, even—is that it empirically looks a lot like Newton’s law of gravity, which you’ll recall from high school physics looks like:

The gravitational force between two bodies is related by (a constant and) the mass of object one, the mass of object two, and the squared distance between them.1

Incredibly, if you just sub out some variable names, you’ll find that trade flows look strikingly similar:

So, almost exactly the same: the volume of exports between country 1 and country 2 is related by (a constant and) the size of country 1’s economy, the size of country 2’s economy, and the distance between them.

This has been borne out by plenty of empirical research (for a brief overview, see Chaney 2018, pp. 151–154).

But you don’t have to stop there! Instead of just geographical distance, you can do other stuff, like “cultural distance” (measured usually by social media connections between countries, shared religion rates, or linguistic overlap); “regulatory distance” (measured usually by tariffs, trade agreements, rule of law measures); or even, yes, geopolitical distance™. And you need not limit your study to exports of goods: you could look at services or financial flows (or actually even people—migration).

The note: geopolitical distance, updated

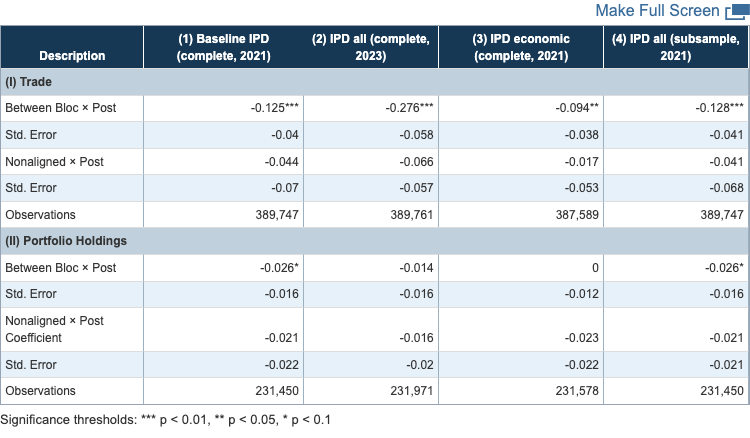

Essentially, the authors do two big things: (1) they explore revised measures of geopolitical distance, drawing on the methodology of a now well-known IMF paper (Gopinath et al. 2024); and (2) use those different measures to explore how they affect trade and financial flow linkages between countries.

I’ll be brief here on the technical aspects, because the note is very short to read, but here are the specifications (IPD = Ideal Point Distance = geopolitical distance measure) in the study, in case of interest:

Source: Airaudo et al. 2025

Essentially, they’ve taken 2021 IPD measures and (a) updated them for 2023 numbers; (b) limited the scores to economic matters only2; and (c) changed the sample period to start more recently (from 1946 initially to 1990). We mostly care about (a)—the updated figures. When changing the specification, points below the 45-degree line have shifted more to the US, and those above it to China (1 = perfectly US-aligned; –1 = perfectly China-aligned).

And they’ve run a nice regression for us:

Source: Airaudo et al. 2025

Takeaways

In my view, there are two big takeaways here.

Elasticity of geopolitical alignment: As the authors point out, updating 2021 figures with 2023 figures (which captures Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) illustrates considerable responsiveness in geopolitical alignment to events over time:

From 2021 to 2023, countries shifted closer to the U.S., albeit from a strong-China starting point. This trend is especially pronounced for Advanced Foreign Economies (AFEs) (light blue dots). This pattern suggests that recent geopolitical developments—such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine and escalating U.S.—China tensions—may have played a key role in reshaping alliances. The fact that the shift is more pronounced among AFEs, which are historically aligned with the U.S., may indicate a tightening of alliances within the Western bloc, particularly in response to economic and security concerns . . . The reclassification under the 2023 IPD implies that countries are reacting to immediate political and economic pressures rather than adhering to long-standing alignments. (emphasis added; citations omitted)

Strength for trade channel, less so for financial flows: While their regression model is quite strong and robust for trade flows, it is considerably weaker for portfolio holdings. This is interesting, not least because it doesn’t seem entirely predictable? I mean, theoretically, trade in goods is a fair bit “stickier” than portfolio investments. Note that the researchers’ measure of portfolio investments strips out foreign direct investments (e.g., an American factory in China—hard to move quickly) and limits it to equity and debt securities (highly liquid and “flighty”). Intuitively: if I’m suddenly worried about country X, it’s a lot faster to sell stocks from country X in my Schwab account than it is to diversify my supply chain of tires/semiconductor chips/whatever away from country X.

And yet . . . trade:

The estimated coefficient indicates that in the post-invasion period, trade flows between countries in different geopolitical blocs are 11.8 percent lower, on average, compared to trade flows between countries within the same bloc . . . This effect strengthens with the 2023 IPD (-24.1 percent), reflecting recent geopolitical shifts.

Portfolio flows:

[There is] some evidence of financial fragmentation, with portfolio holdings between countries in opposing blocs declining by 0.3 percentage points post-invasion in baseline and post-1990 IPDs. However, results are weaker and less robust across specifications, particularly in 2023 and economic votes IPDs. Meanwhile, the coefficients for nonaligned countries remain small and insignificant across all specifications, reinforcing the idea that financial flows among nonaligned countries were less affected by geopolitical tensions.

So, what?

There are some policy implications here.

Gravity model aside, the pure elasticity of geopolitical alignment should be a wakeup call for policymakers in Washington: studied diplomacy years in the making can be shifted quickly as the result of a changing geopolitical landscape, and historic alliances don’t count for much. While the period 2021–2023 saw a shift toward the US, it is very likely that recent American policy shifts are moving the needle in the other direction (which we’re already seeing evidence for). The bar for pushing countries—even old friends—away (even if just to “neutral”) is pretty low. In other words, the “loyalty” or “momentum” effects of geopolitical alignment are smaller than we might have thought.

This model is explicitly not accounting for tariffs, which I’d imagine will have a weird and somewhat endogenous relationship. On the one hand, tariffs have an additive effect on trade, according to general gravity model logic (i.e., tariffs = less trade). On the other hand, given the way Trump has been messaging about tariffs (because Canada is meant to be the 51st state, etc.), they probably also act through the geopolitical channel. All to say: if the point is to drive trade away from your country, it’ll probably work!

Trade and portfolio flows are different, yes, but ultimately will be related in the long run. Research (Gopinath and Stein 2018) shows that a currency’s status in the world often begins with its issuer country’s trade: if I build up a lot of dollars from trading with the US, I’ll have a lot of dollars to invest, so I’ll go buy dollar-denominated securities, or lend my dollars out in the Eurodollar market, or whatever. In short, these things—trade and portfolio flows—are not one-to-one related, but they are ultimately related, even if with a long and variable lag. This means that geopolitical distance, in some way, ultimately will impact the role of the dollar, yields on American debt, and the safe-haven status of American securities.

Wherefore art thou, alternative?

We might ask, speculatively, who stands to gain from a potential reshuffling of the geopolitical pack, according to the model presented in this research note. Probably Europe. The European Union (EU) is, in real (non-PPP-adjusted) terms, the second-largest economy in the world, and the euro is the second-mostly widely used international currency.

Of course, China should stand to gain too, but there are two caveats with China. First, per the research note here, most advanced economies (i.e., where much—albeit less than yesteryear—of the trade and financial flows comes from) are not clustered around a China-oriented geopolitical alignment: they are clustered around a more neutral or US-leaning alignment. So, even if they were pushed significantly from the US, that would put them closer to the center of the geopolitical scale (where I would hazard to guess is where EU nations will cluster), but it would take a lot to get them voting with Beijing consistently. Second, while China is a trade behemoth, its capital account is relatively closed.

The EU’s open capital account, large and developed banking sector, rule of law, deep and liquid capital markets, and internationalized currency with emergency liquidity backstops (swap lines and FX repo facilities) make it a highly attractive location for portfolio flows, even when growth has been disappointing. Recent increases in euro-denominated safe assets as a result of the German-led defense spending spree will only buttress those dynamics. Brussels, it’s yours to lose.

You can follow me on Twitter (X) @ArnoldVincient, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

This work is independent from and not endorsed by the Yale Program on Financial Stability or Yale University; all views are my own.

Please don’t email me about General Relativity.

The way these geopolitical distance figures are created is by using voting patterns in the UN General Assembly (so, if you vote with the US all the time, you’re very US-aligned). Here, they limit the votes to votes on economic questions.