Reading List No. 1 (?)

a discursive-ish list of things

Programming Note: I’ve been quiet on here for a couple of months in part because I spent a few months at the New York Fed (hooray) and was muzzled; in part because life is busy; and in part because, as I preview in the About page, “there is no cadence; I write only when I think I have something useful to say that’s worth my readers’ time.” That is very much still true: no cadence and no spamming.

That said, I’m trying something new (maybe just once, we’ll see!) while I work on a two-part essay series (yay), because (1) I like when other people do it; (2) I hope you might like when I do it; (3) I see things I think my readers might enjoy, but about which I cannot justify devoting significant writing and this offers a compromise. I’m going to drop a few links here I’ve found interesting, and maybe say something brief about them. (As a housekeeping issue, I’ll mention that while I’ll always try to include some free/non-gated stuff, there may be pay-walled or journal-walled content. Sorry.) If you love it, lmk; if you hate it, lmk.

Democracy does not cause growth. Guillermo Vuletin, Julia Ruiz Pozuelo, and Amy Slipowitz. Brookings.

This is a succinct piece by scholars of a longer academic study, which nicely summarizes their main argument. That argument is more or less a methodology/econometrics critique, but the upshot is material to development and political economy folks alike. A common causal inference (“does X cause Y”) tool is two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression, d.b.a instrumental variable regression (IV).1 A common approach in the literature was to instrument democratization with waves of democracy—i.e., your country gets democracy because your neighbor got democracy and it spreads contagiously, which is nice because you can say that democratic waves have nothing to do with economic outcomes and then conclude, after running an IV regression, that democracy causes economic growth. These authors critique this argument by saying, essentially, “that’s a bad instrument, you’re probably getting waves of democracy precisely because the economy has hit rock bottom.” And it looks like they’re right: once you control for the economic-origins-of-democracy endogeneity, the growth-causing features of democracy disappear. This sits somewhat uncomfortably with the “institutions matter” camp, although there’s plenty of evidence in their favor too (also using IV!). I’m not sure I’m sold on their conclusion yet (as someone partial to institutions-matter), but credit where credit’s due: the weak instrument critique here is clever.

What would happen if Congress repealed the Fed’s authority to pay interest on reserves? William English and Donald Kohn. Brookings.

This topic has been in the headlines of late and has garnered a rather unusual amount of partisan salience. Good thing, then, that the experts have weighed in with an explainer. Even among Fed-watchers, monetary policy implementation regimes are relatively esoteric, so this is a welcome post.

A couple of points I’ll highlight, in defense of interest-on-reserve-balances (IORB):

When the Fed didn’t pay interest on bank reserves but forced banks to hold them, it was an implicit tax. This is something the “Fed needs oversight and democratic legitimacy” people should be opposed to, and it was distortionary.

It is by now the norm among advanced economy central banks (for a reason).

Ample (and/or abundant) reserves systems are practically relatively straightforward to run. Scarce reserve regimes are harder to run, and monetary policy slippage (losing rate control) is more likely to occur, as well as funding shortages, when you’re in a scarce reserves regime.

The main argument we’re hearing against IORB is that it’s a fiscal cost. Which I find interesting! An interest of mine/this site is that the line between the fiscal and the monetary is blurrier than we give it credit for. But these arguments miss the mark with superficial accounting and belie an understanding of the mechanics, regardless of where you stand on the size of the Fed’s balance sheet debate. It’s a tractable and timely piece.

What the West Gets Wrong About China. Rana Mitter and Elsbeth Johnson. HBR.

This is somewhat trodden territory for China-watcher types, but it’s a nice readable essay from which the non-China watchers among us will benefit. The authors—an historian and management professor—attempt to do some myth-busting about China, in three purported myths: (1) economics and democracy are two sides of the same coin; (2) authoritarian political systems can’t be legitimate; and (3) the Chinese live, work, and invest like Westerners. I don’t wholly agree with the authors in all they say here, which is probably no surprise, and I’m not even convinced most people believe myth number 3. Nonetheless, it’s a well-written answer to the “how did China not become like us” question.

The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870–2015. Òscar Jordà, Katharina Knoll, Dmitry Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick, Alan M. Taylor. NBER.

Something of an instant classic, this is one of my favorite academic papers, if for no other reason than their rockstar title. What a headline. There’s a lot to cover here, which, as I’ve previewed, I won’t do. But this is very much worth at least a student-read (abstract, intro, conclusion, charts). For your convenience, I’ll just paste here the abstract because it’s so cool:

What is the aggregate real rate of return in the economy? Is it higher than the growth rate of the economy and, if so, by how much? Is there a tendency for returns to fall in the long-run? Which particular assets have the highest long-run returns? We answer these questions on the basis of a new and comprehensive dataset for all major asset classes, including housing. The annual data on total returns for equity, housing, bonds, and bills cover 16 advanced economies from 1870 to 2015, and our new evidence reveals many new findings and puzzles.

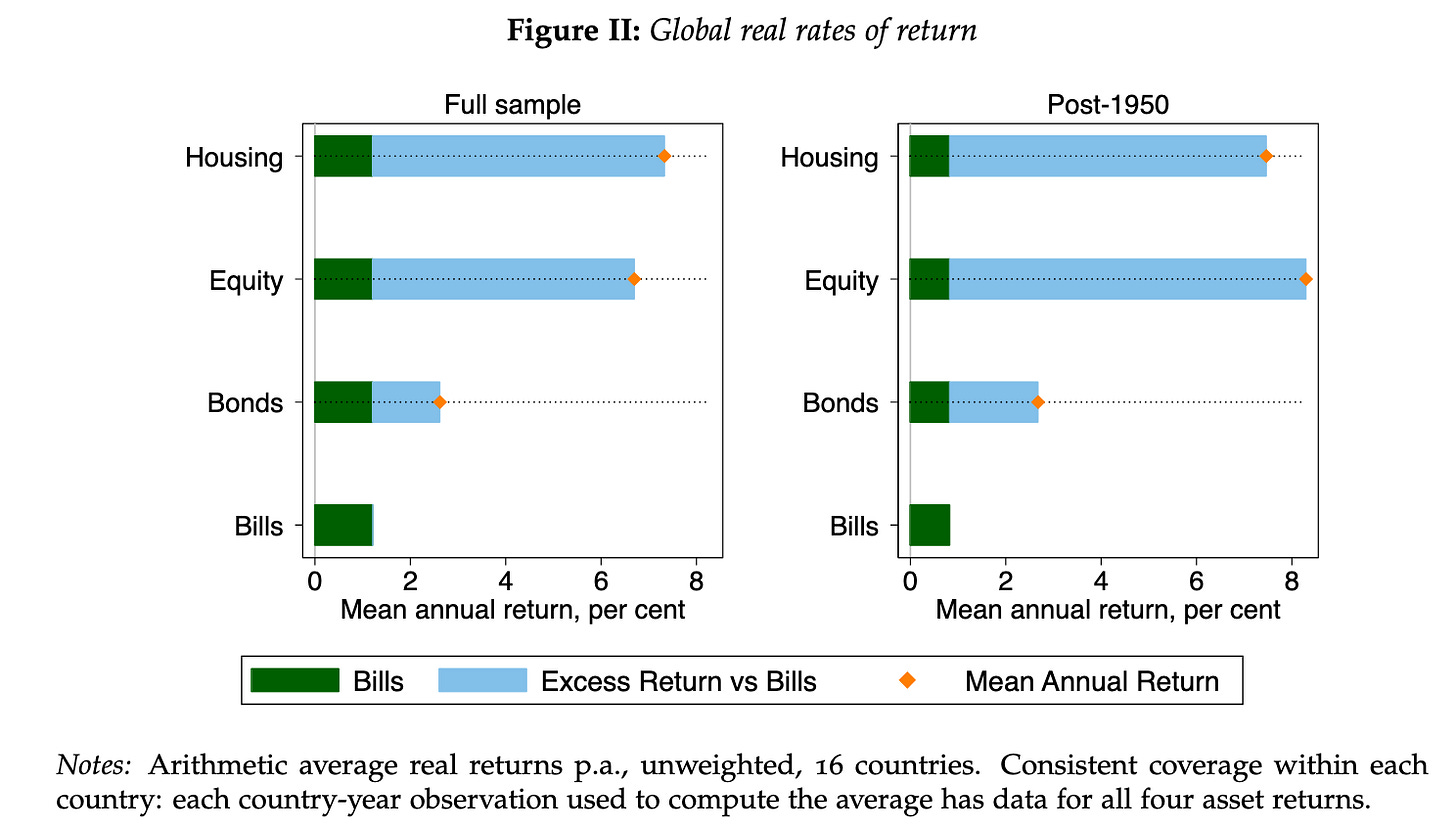

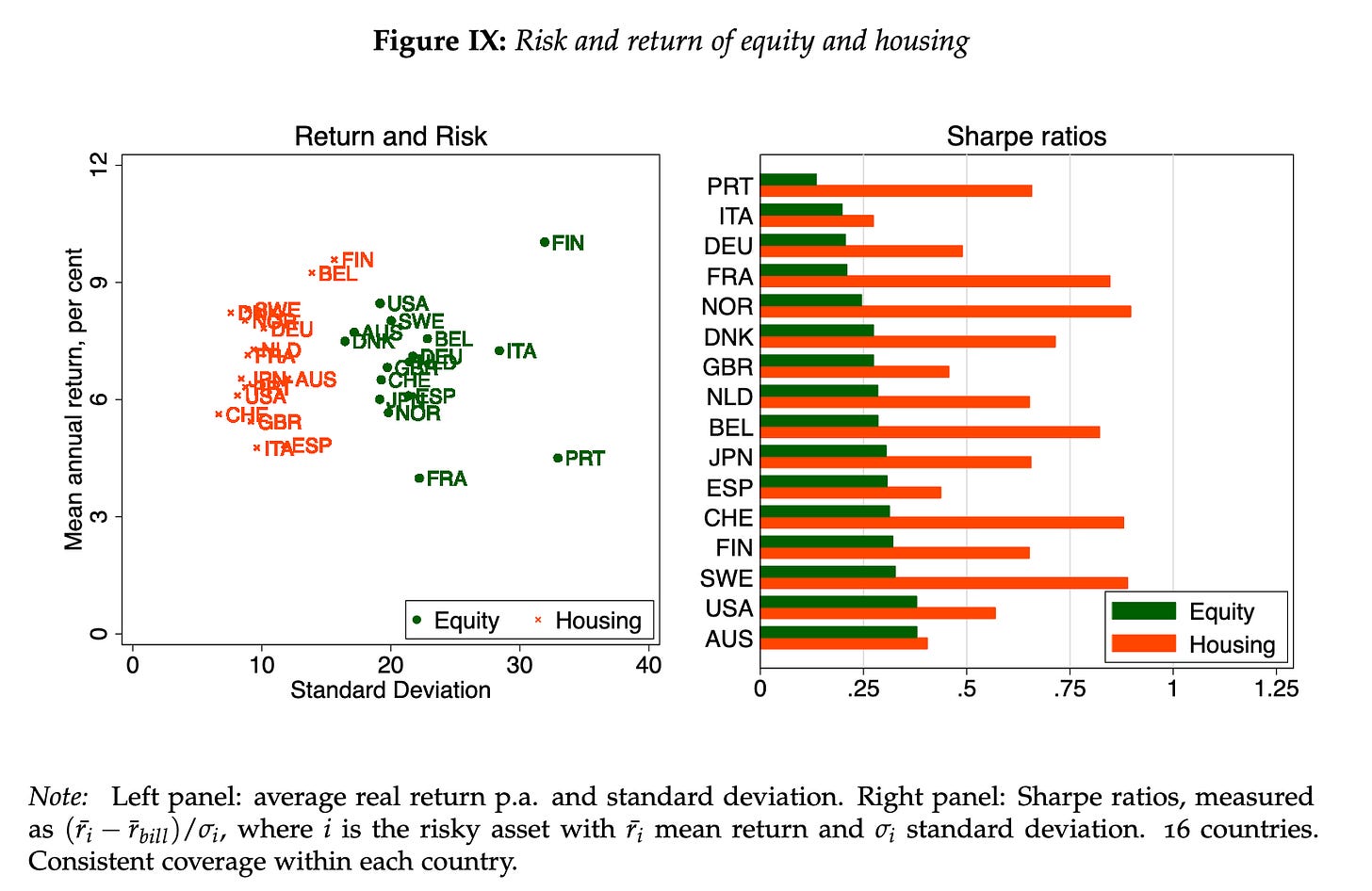

Also just . . . data on real estate returns from Norway in 1871? Awesome. There are lots of upshots, but the thing I noticed starkly was that housing not only historically has the highest returns, it also has the highest risk-adjusted returns (Sharpe Ratios = excess return/sigma):

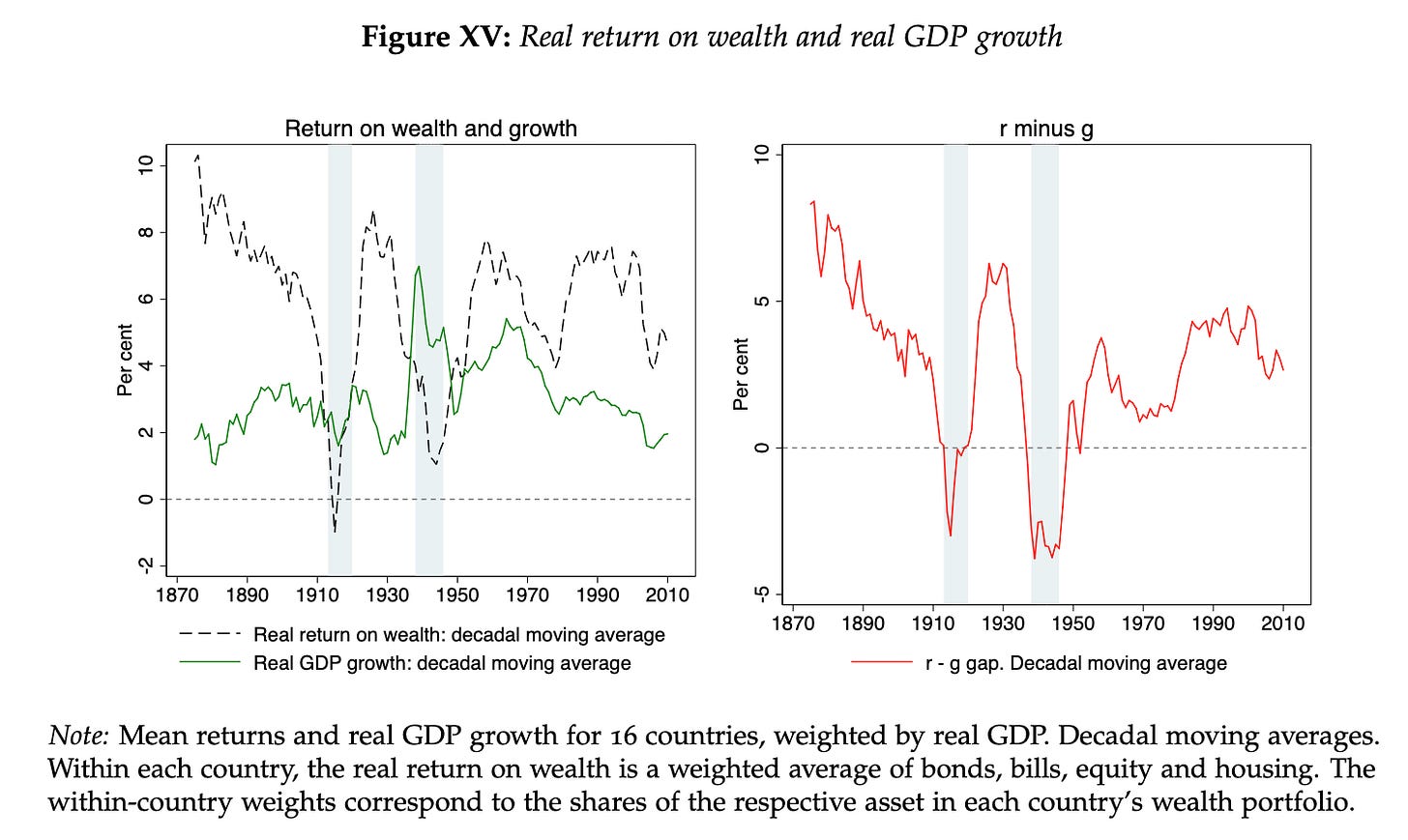

Another cool thing about this paper is that it’s both finance and economics, and necessarily has something to say about the macroeconomy, in this case about inequality. If r > g, in other words, returns to financial assets (wealth) are higher than the returns of the economy writ large, you’d expect inequality to expand, and their dataset has something to say about this too:

TL;DR: aside from wars, r >> g. Anyways, the paper is worth a skim at least. Reactions to it could vary from “become a real estate mogul” to “become a communist” so, ya know, idk, pick your poison, but either way, it’s a very cool paper.

***

Fin. Happy reading.

I’ll limit explanation of that here; those who are familiar with normal regression can easily parse this method out. But the important thing is that central to the approach is finding something that explains/correlates with X but has nothing to do with Y.