Stablecoins and the Dollar System

mostly more of the same

I recently came across this Fed note (otherwise about CBDCs), which included the following:

demand for dollar-denominated stablecoins could strengthen or weaken the role of the dollar, depending on whether the source of demand is dollar-denominated or foreign currency-denominated assets

This raised an interesting question: in a world in which stablecoins begin to gain share against traditional dollars in their uses as money, what types of effects would that have on dollar dominance or otherwise the features of the dollar we think about (e.g., geopolitical leverage, the Treasury market, etc.)?

Balance Sheet Basics

One way to think about this question is to think about stablecoins like banks. Stablecoins are basically money market mutual funds (MMMFs), [1] which in turn are basically banks. Not like in a narrow legalistic way obviously, but in terms of the business they do and the balance sheets they have.

Banks are banks because they do banking, i.e., maturity transformation—turning claims on long-term illiquid risky stuff into short-term liquid safe liabilities, i.e. money. We all know how it goes: banks take deposits, which are short-term liquid claims that we treat as money and that’s the liability side of the balance sheet. On the asset side are things like loans and securities. In other words, your $1 deposit is backed by (close to) $1 in assets of varying quality depending on the riskiness of your bank.

MMMFs are like banks because they basically do the same thing. You give a MMMF a dollar (probably itself in the form of a bank deposit) and the MMMF gives you a short-term liquid claim on it (like your bank deposit but called a share) and then it invests in stuff like bonds (in practice, safe government debt). So, it’s basically doing banking and experiences runs just like banks do (see the run on the Reserve Primary Fund during the Global Financial Crisis).

Stablecoins are in essence the same thing. You give the stablecoin issuer a dollar (or a dollar’s worth of euro, yen, bitcoin, whatever) and it gives you a short-term liquid claim on it (a “coin,” basically a MMMF share, same idea as a bank deposit), and it in turn invests in stuff like bonds (or repo or crazy stuff, depending on the riskiness of your stablecoin issuer). Stablecoins experience runs just like MMMFs and banks because they’re all doing the same runnable thing: maturity transformation.

So, what matters here is the asset side of the balance sheet. The question of the moneyness of a bank deposit is ultimately a question of how safe and liquid the asset side of its balance sheet is (and how much equity it has in order to absorb losses). The same thing is true of MMMFs: the safer and more liquid their investments the safer and more money-like their shares.

Plus Ça Change

Back to the Fed question, restated here:

demand for dollar-denominated stablecoins could strengthen or weaken the role of the dollar, depending on whether the source of demand is dollar-denominated or foreign currency-denominated assets

Let’s first consider that the demand is dollar-denominated, and let’s assume for simplicity’s sake that the stablecoin issuer is a good one (i.e., they’re operating with adequate—read bank-like—equity levels and don’t make dumb investment decisions). In this case, Person A has a “dollar” in bank deposits—that is, they have a $1-worth claim on the bank’s dollar-denominated assets, like Treasuries and dollar-denominated mortgage loans. They then take that dollar from the bank and send it to our stablecoin issuer. Bank is down $1 in liabilities and assets; stablecoin issuer is up $1 in liabilities and assets. Stablecoin issuer backs its short-term liabilities (deposits, “coins” if you must) with some safe dollar-denominated assets, like Treasuries and dollar-denominated mortgage loans.

So, we’ve basically accomplished nothing here, insofar as the role of the dollar is concerned. None of this has moved outside of the US (outside of the Fed, ultimately), and for the dollar role, the claim has just shapeshifted from being a bank deposit dollar to a stablecoin-issuer deposit dollar: all claims on dollar assets, functionally the same thing.

This is not fictional stuff. Take Circle’s USDC. You don’t have to go beyond the homepage to see that it’s de facto a MMMF (my emphasis):

USDC is backed by the equivalent value of US dollar denominated assets held as reserves for the benefit of USDC holders. Cash is held at regulated financial institutions. The portfolio of the Circle Reserve Fund, which can contain short-dated US Treasuries, overnight US Treasury repurchase agreements, and cash, is custodied at The Bank of New York Mellon and is managed by BlackRock.

This is just the “I give you a deposit, you go do Treasury repo” thing that lots of MMMFs (and banks) do. There’s no skirting the dollar here; a share (“coin”) of Circle’s USDC is just a claim on Treasuries and dollar cash held at Fed-regulated insured banking institutions.

Tether’s USDT is similarly reserved. A look at the asset side of the balance sheet reveals that, while it’s a little bolder than USDC, it’s pretty much (85%) backed by short-term dollar claims (as of March 2024):

This is no libertarian crypto thing; it’s a money market fund (albeit a slightly edgy one). And even if the stablecoins were invested in not so safe assets, so long as they’re dollar denominated you still haven’t done anything to the role of the dollar (remember the Reserve Primary Fund was invested in Lehman Brothers commercial paper—still dollars, though).

Nothing new under the sun.

The Other Side of the Coin

Now to the second clause: foreign currency-denominated assets. Theoretically, a dollar-denominated stablecoin issuer could back its deposits (coins) with not all dollar-denominated assets. Some do. [2] Consider again our bank analogy: Swiss banks during the Global Financial Crisis had Swiss-franc-denominated deposits but often owned dollar-denominated assets.

This gets tricky: we think of dollars, for example, in whatever form (central bank reserves, bank deposits, etc.) as ultimately claims on dollar-denominated assets (bank assets for bank deposits, and the US government for cash, Treasuries, or Fed reserves—and a claim on the US government is a claim on tax revenue). So, for the Swiss banks in this example, it’s a bit weird: the Swiss franc deposit-cum-money isn’t actually or wholly a claim on Swiss franc assets; it’s a claim in large part on dollar-denominated assets. So, it’s a bit less money-like in the sense that it’s a bit less liquid. The bank has to do liquidations in two markets in order to pay back its depositors: (1) the market for the assets it’s going to sell and (2) the foreign exchange market. That makes things a bit less liquid and the Swiss franc deposits a bit less Swiss franc-y.

If a Finnish person goes out and buys a $1 share of a stablecoin, that deposit (“coin”) is a promise to pay $1, but it’s possible that the stablecoin issuer, for whatever reason, isn’t really invested in dollar-denominated assets on the asset side of its balance sheet. Instead, it could own German bunds, Singaporean dollar bank debt, and securitized Thai baht-denominated commercial real estate obligations. Who knows! In such a case, Person A’s “dollar deposit” could be made not in dollars (they could buy the share—coin—using bitcoin or Finnish krone) and would be financing non-dollar assets. It’s kind of a mythical dollar. Their screen would say “you own a right to $1,” and like, they would theoretically but basically, they just deposited some Finnish krone or bitcoin or whatever and financed the purchase of euro-denominated bunds or Singaporean bank debt or something. No dollar-denominated stuff got funded. In fact, the dollar was completed skirted! The depositor is getting the “safety” of a dollar peg, but this is fundamentally no different than buying Emirati dirhams: they’re pegged to the dollar and don’t have to be backed by dollar-denominated assets. Now, just like the dirham, they could lose that peg and fail spectacularly. But from a purely what-does-this-do-to-the-dollar-system perspective, such a dollar-denominated stablecoin would, in a very real sense, eat away at dollar share (of payments, “deposits,” or whatever it’s being used for).

But . . . why? It seems like a bad idea. Buying a claim on $1 that is backed by, uh, not dollars, seems like kind of a risky move. I mean, theoretically, one could set up a MMMF that promises to pay $1 per share upon redemption and then invests the share proceeds in Egyptian sovereign debt but that would be, you know, a bad MMMF and would probably collapse.

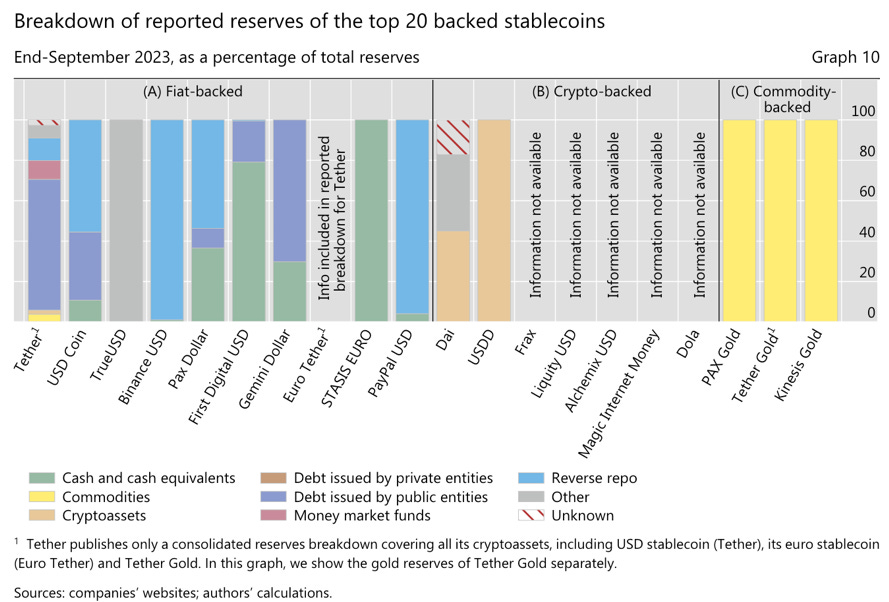

In practice, to my knowledge, there aren’t any significant foreign currency-backed dollar-denominated stablecoins. [3] What does exist, however, is a dollar stablecoin backed by crypto and/or sometimes commodities. Here’s a pretty concise view of the playing field from fall 2023:

You Can Run (on the Coin) . . .

So, if you’re this stablecoin issuer, and you have promised to pay $1 per share (coin) to your depositors, and you have only or mostly non-dollar assets, then from a geopolitics perspective, yes, you have succeeded in eroding dollar share of global money. But, that’s also super risky for all the above reasons and you probably need insurance if you’re going to live to fight another day (i.e., when you get a bank run). Now, your depositors (coin-holders) could have deposit insurance, thus weakening the incentives to run. But they don’t because you’re not a bank; you’re a stablecoin issuer. So now you need insurance, and really you need dollar liquidity insurance if you’re going to survive a run. And mind you, runs absolutely do happen, sometimes in spectacular fashion. [4] In fact, a group of researchers at the BIS surveyed the world’s largest stablecoins and found that, while not all experienced fatal runs, not a single one had been able to maintain parity with its peg.

In practice, this is what the foreign exchange (FX) forward and swap markets are for. But hedging FX risks is expensive—last year, a one-year euro-dollar hedge costed well over 100 basis points. For a company operating as essentially a money market fund, these costs grow prohibitively high. Perhaps a bank can give you that dollar liquidity insurance for a fee. Almost certainly the same would be true of a fee-based dollar liquidity facility: I can only imagine it would be even more expensive. But let’s assume you could use such a facility and let’s further assume it’s economical to do so. Fine. At some point, though, you—the stablecoin issuer—might be pretty big (as big as the bank), so that’s a lot of dollars. The bank might then need dollar liquidity insurance, so again, would need to (1) hedge affordably or (2) in extremis, get dollars from the central bank, which would need to have a Fed swap line or sufficient access to FIMA repo. (This all in the absence of a CBDC and access thereto available to foreigners, which is an entirely separate discussion.) Hence why so many euro-area banks in 2008 needed dollar swap line funding—they could have hedged all their FX risk, but it would’ve eaten away at their margins. To be fully protected against FX liquidity risks in a way that isn’t prohibitively expensive means that, in the left tail, you need liquidity insurance via central bank swap lines or repo facilities.

But again, the above is mostly theoretical, because such a dollar-denominated but yen-backed stablecoin doesn’t exist (at least in non-de minimis quantities). The practical manifestation here is a crypto-backed dollar-denominated stablecoin, but here the point is even more salient: bitcoin doesn’t get swap lines. Nor is there a deep bitcoin-dollar swaps or futures market (yet, at least—but it would be crazy expensive if it did exist!).

A (deep breath) foreign-incorporated issuer of a bitcoin-backed dollar-denominated stablecoin (whew) has one last refuge: (very expensive) paid dollar liquidity provided by a bank. And that might work in a run scenario, but something about “foreign-incorporated issuer of a bitcoin-backed dollar-denominated stablecoin” makes me think they’re after something else here: sanctions evasion. Not so quick: they won’t get away with that either, so long as they have dollar liquidity insurance.

But You Can’t Hide

The other side of this coin (pun very much intended) is sanctions (and by “sanctions” here I mean truly sanctions, but much of the following will also apply to anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing regulations as well). When folks in cryptoland think about the dollar system and trying to get away from it, they’re typically thinking about doing so for one of two reasons: they’re libertarian types (“freedom maximalists”) and don’t want big brother controlling money (cue facepalm) or they’re criminals/foreign actors trying to evade sanctions regulations. For the first group, the vast majority of dollar stablecoins (i.e., the stable ones) won’t help—as we’ve seen, they’re ironically backed by the most government thing ever: Treasuries. Escaping the domination of the US government by financing its fiscal debt is (a) hilarious and (b) incoherent.

The second group though should be taken more seriously. This is not theoretical stuff: according to crypto research outfit Chainalysis, stablecoins were responsible for 83% of payments to sanctioned companies or individuals (stablecoins represented just 59% of crypto transaction volumes overall in 2023).

Ostensibly, when making payments with stablecoins—even dollar-denominated ones—one is moving said stablecoin around a blockchain and thus not interacting with the dollar system in legal terms. That looks and smells like successful sanctions evasion.

Before diving in, though, let’s revisit a primer on US sanctions jurisdiction, from another post nearby:

At their core, the strength of US (and, to a lesser extent European) sanctions rest on the centrality of correspondent banking relationships and payments systems. In other words, to use dollars, you’ve gotta have an account at the Fed, or bank with someone who has an account at the Fed, or bank with someone who banks with someone (and so on, you get it) who has an account at the Fed. That’s the magic behind the legal force of sanctions: US legal jurisdiction covers US entities and ultimately, if you have to clear payments through the New York Fed, you’re dealing with a US entity. This is a source of frequent misunderstanding: while sanctions are targeted at foreign institutions, they actually apply to American ones only. But the vast majority of payments go through the Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS), which is comprised of American institutions or foreign institutions with a US bank branch (and therefore still subject to US law). So, in other words, sanctions don’t target a central bank receiving a currency; they target companies’ abilities to send and receive that currency. For example, US sanctions blocking dollar payments would fail to work if a Bolivian citizen bought US cash bills at a money-exchanger in La Paz and then went across the border and used that cash to pay for goods or services in the streets of Peru. There’s no US company or natural person involved in the movement of that money, so the sanctions don’t help.

Another piece of sanctions context/vocabulary that’s helpful here is secondary sanctions. This is where Company X isn’t sanctioned, but it’s doing stuff the US doesn’t like (like aiding and abetting sanctions targets), so the US in turn sanctions it. For example, imagine a Moroccan oil broker is doing tons of business with sanctioned Russian vessels. The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC—the sanctions folks at the Treasury) could, in turn say, hey, we don’t like you, so now you’re sanctioned.

With that ground-clearing out of the way, there are two questions here, one interesting and one not so interesting. Let’s start with the slightly less interesting question first: what if the stablecoin issuer is a US company (or owned by a US company, or whose employees are mostly US citizens, etc.). Can you evade sanctions by using their coin? No. I mean, you could to the extent that maybe their compliance is lame and you don’t get caught, but that’s no different than saying you can get away with robbery if you don’t get arrested (and even US banks fail to catch all sanctions violations). But the point is, that company—whose stablecoin could be backed by anything at all, including non-dollar stuff exclusively—is subject to the jurisdiction of OFAC. Don’t take it from me; here’s OFAC FAQ No. 560:

Are my OFAC compliance obligations the same, regardless of whether a transaction is denominated in digital currency or traditional fiat currency? Yes, the obligations are the same . . . U.S. persons and persons otherwise subject to OFAC jurisdiction, including firms that facilitate or engage in online commerce or process transactions using digital currency, are responsible for ensuring that they do not engage in unauthorized transactions prohibited by OFAC sanctions, such as dealings with blocked persons or property, or engaging in prohibited trade or investment-related transactions. Prohibited transactions include transactions that evade or avoid, have the purpose of evading or avoiding, cause a violation of, or attempt to violate prohibitions imposed by OFAC under various sanctions authorities . . .

Now for the more interesting question: what if the stablecoin issuer is a foreign company (like, fully—incorporated abroad, operating 100% abroad, no American shareholders or employees, etc.)? There are two substituent scenarios here: the first is that the issuer is backing their coins with dollar assets, and the second is that they’re backing the coin with non-dollar assets exclusively. In the first case, they’re in trouble—if they’re facilitating transactions with sanctioned individuals or companies, then US banks aren’t going to deal with them, so they’ll lose access to their dollar assets. As a technicality, the stablecoin issuer in this scenario isn’t sanctioned itself, but the reputational and regulatory risk of dealing with an entity actively facilitating sanctions violations is too much for banks, which will, as a matter of policy, pull away. And even if they didn’t, the US could sanction that stablecoin issuer (secondary sanctions here) and it would be game over: they’d be fully cut off from the dollar system and thus unable to issue the stablecoin. So, no—can’t dodge sanctions here (in the long run at least). Here’s the end of OFAC FAQ No. 560: “Additionally, persons that provide financial, material, or technological support for or to a designated person may be designated by OFAC under the relevant sanctions authority.” Tidy.

Now, to be fair, it surely seems possible that a foreign-currency backed dollar-denominated stablecoin could put enough distance between itself and US legal persons (both companies and individuals) so as to fly under OFAC’s radar. That certainly happens in other industries. But the ability to do so is inversely correlated with scale: OFAC probably won’t expend resources on a $10 million market cap stablecoin traded in a far-flung corner of Baluchistan, but the larger a coin becomes the harder it is to hide. Probably someone can get away with sanctions facilitation via stablecoin, but not indefinitely and not at scale.

Another way around this is that the reputational damage isn’t bad enough yet, and so American banks continue to do business with said issuer, even if it’s allowing sanctioned folks to use its platform. This is what appears to be going on at Tether. Here’s JP Koning on a recent Tether scandal involving some cheeky Russians and a sanctioned Venezuelan oil company:

USDt transfer occurs on the books of Tether (which is registered in the British Virgin Islands), completely bypassing the New York correspondent banking system. So when they paid with USDt, Serrano and Orekhov didn’t “cause” a U.S-based actor to do anything wrong.

Put differently, if the Russians and Venezuelans had conducted all their transactions with Tether and cash, and avoided bank wires altogether, it would have been impossible for the U.S. to indict them for violating the [International Emergency Economic Powers Act]. Thus, not only is Tether “quick like SMS,” it also provides a degree of safe harbour from sanctions law.

Right, but to be sure, this isn’t a question of strict legal capability. I mean, OFAC could sanction Tether, denying it access to dollars to back its coin. Less legally, Wall Street could get too scared and could stop doing business with Tether. Or Tether could decide it doesn’t want any of that and so voluntarily submit to OFAC regulation anyways, which is what in fact it has done.

And the Treasury more broadly is aware of the risks here. The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) in the US is on the case also (they handle money laundering and terrorism financing, as distinct from—though often related to—sanctions). In its 2021 report on stablecoins, the FDIC, OCC, and President’s Working Group on Financial Markets made it clear that Treasury wasn’t asleep at the wheel:

While regulations are broadly sufficient to cover stablecoin administrators and other participants in stablecoin arrangements, Treasury will pursue additional resources, which could enable FinCEN, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and federal functional regulators to increase supervision of these regulations. This could result in better private sector compliance and, where it does not, could lead to enforcement actions for non-compliance.

Now for the really interesting one: foreign stablecoin issuer with non-dollar assets backing a dollar-linked stablecoin. Can it get away with it? Theoretically, yes, so long as it’s only promising to pay back one dollar’s worth of something else ($1 worth of ether or something). Now, yes, if that sounds like not really a dollar stablecoin, that’s because it isn’t: you can’t exchange your coin for a dollar [5] (because if you could, the issuer would have dollar assets—see above, or could buy dollars on the FX market). But it’s getting close because it’s promising you stable value, which is probably what you’re looking for anyways. But, first, for all intents and purposes, this isn’t really a dollar stablecoin, and second, when it gets run on, it’s in trouble. If its backup is a dollar liquidity facility from a bank accessing dollars, then it’s exposed again to the dollar banking system and therefore OFAC. If its backup is liquidating its assets for euro/bitcoin/ether/whatever and then buying dollars on the FX market, then it has to interact with the dollar banking system to make those dollar purchases, so again, OFAC territory. If it doesn’t have the dollar liquidity facility, it’s probably going to die in the run. So, this stablecoin issuer probably could get away with dodging the dollar system in extremis, but just the description “dollar stablecoin issuer fully cut off from the dollar system” should alert us to the fundamental weakness in the business model here.

Most basically, if you’re promising to pay people (depositors) dollars, you need to have some dollars. And look, if you’re operating in or interacting with the dollar system in any way, you are subject to either (1) OFAC jurisdiction or (2) the ever-looming threat of secondary sanctions. This idea, visualized:

To Be Continued?

We have to do a quick detour here because OFAC jurisdiction could potentially be getting changed. The above analysis still holds with the laws currently on the books. But OFAC, being aware of the issues surrounding stablecoins and sanctions violations, has made a legislative proposal to the Senate Banking Committee that would massively expand its reach. While I haven’t seen this proposal get anywhere further than a post on X (formerly known as Twitter), the contents are pretty significant:

Now, again, it’s unclear (and unlikely) that Senate Banking is doing anything with this. But directionally, it seems in line with public comments made by Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Wally Adeyemo on the same issue (my emphasis):

We cannot allow dollar-backed stable coin providers outside the United States to have the privilege of using our currency without the responsibility of putting in place procedures to prevent terrorists from abusing their platform. And we cannot permit offshore financial services providers to use jurisdiction-evasion tactics to avoid complying with our laws. We are working to close these gaps and others.

While it remains unclear at this juncture where these types of proposals will go and how watered down they might get, it seems clear that Treasury is thinking creatively about how to police dollar stablecoins with no obvious US nexus that they would typically need in order to trigger OFAC jurisdiction (see OFAC primer above).

Greenback Escape Hatch?

This note has carried on with the condition that the stablecoins are dollar stablecoins and that probably makes sense, given that roughly 99% of stablecoin market cap is dollar-linked. But you might find yourself reading the sanctions bit and thinking “hm, if all I want is a stable store of value and a way to low-key transact with someone in Pyongyang” then you might question the dollar premise. Central banks care about holding dollars in large part because they care about holding Treasuries (the deepest and most liquid market in the world and all the rest). But if I’m a sanctions-dodger or even just someone in Argentina desperately seeking refuge from three-digit inflation, then I don’t necessarily care that it’s a dollar stablecoin, all I care about is the stable part. I don’t care about picking up 300 basis points on Agency debt or having access to the triparty repo market, I just want to have not pesos!

That’s all correct I think, on the merits. The issue here though is the same issue facing every other kind of money: it still has to be backed by assets, [6] and safe assets are in limited supply. This is like asking “well instead of buying US government debt, why can’t banks/MMMFs/etc. just buy French sovereign debt?” They can! There’s just not that much of it. Sure, you can have a euro-stablecoin, and they do exist. They’re backed by euro-denominated safe assets. Those are a thing, they just exist in much more limited supply than dollar-denominated safe assets.

This is not a stablecoin thing; this is a money thing in general. This is precisely why the renminbi is struggling to displace the dollar—not because it can’t rival the dollar in being used as a means of payment (a technological/network effect issue), but because there just isn’t that much renminbi-denominated safe and liquid debt to support the issuance of a bunch of renminbi money (a moneyness/market depth issue).

Blockchain Dollarization

For now, we have mostly dollar stablecoins, which are safely dollar money. But perhaps, for the role of the dollar, this stablecoin thing is not only not bad, it could very well prove to be good, that is, supportive of the global role of the dollar. Why? Because lots of people around the world looking for the safety and protection of the dollar—think Argentinians currently using dollar cash to shelter from inflation, or citizens living in countries with highly volatile currencies, like Turkey—can, theoretically, more easily access dollar money with nothing but a smartphone.

This lands us I think where Fed Governor Chris Waller has described:

About 99 percent of stablecoin market capitalization is linked to the U.S. dollar, meaning that crypto-assets are de facto traded in U.S. dollars. So it is likely that any expansion of trading in the DeFi world will simply strengthen the dominant role of the dollar.

There’s no rule saying stablecoins have to be linked to the dollar (but we think most will be for the foreseeable future because of safe asset supply issues), but for those that are, the dollar system itself is inescapable—dollar stablecoins are just another form of dollar money, just like bank deposits, physical cash, and MMMF shares. If anything, what a dollar stablecoin has managed to do is simply create more dollars and make them more easily accessible around the globe!

Stablecoins = dollar death? Fact check: false.

Stablecoins = more dollarization? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Existing stablecoins ≈ the same or more dollarization? Fact check: true.

(Disclaimer: This work is independent from and not endorsed by the Yale Program on Financial Stability or Yale University; all views are my own.)

[1] There are other useful analogies here too. Iñaki Aldasoro, Perry Mehrling, and Daniel H. Neilson have analogized stablecoins to the Eurodollar market, which they argue is the appropriate money-view analogy. For our purposes, either analogy here works (or others, like wildcat banks)—what matters is that the stablecoins are doing liquidity transformation and acting as (ostensibly) safe assets used as means of payment and stores of value (money).

[2] Broadly, whether dollar or otherwise, stablecoins can be broken down into four types, courtesy of researchers at the BIS (paper here, p. 4): fiat-backed, crypto-backed, commodity-backed, and unbacked (*gasp*).

[3] Perhaps it’s worth asking why. For the financial literati out there, one will recall large foreign exchange mismatches in emerging market banks (e.g., Mexico pre-1994, Southeast Asia pre-1997). It seems logical to conclude that one might expect the same thing here (history rhyming at least). But recall that in large part, those banks had serious debt instruments on at least one side of their balance sheet: they were buying up dollar-denominated debt or loans while taking deposits in local currency, or they were accessing dollar debt markets for funding while extending credit in local currency. With stablecoins, you can’t yet get a loan or buy a Treasury in USDT. So, the use cases are more limited: stable store of value, cash management between crypto trades, etc. That’s not to say it’ll remain that way, but for now the limitations on the coins as means of settlement probably help to explain why the asset sides of their balance sheets remain mostly dollars.

[4] This isn’t a note about stablecoin runs, but there’s plenty to see here. See, e.g., the BIS here; Ahmed, Aldasoro, and Duley here; and Kelly here.

[5] In fact, this is really like a foreign exchange futures contract: you’re buying the right to redeem one unit of coin for one unit of ether/bitcoin/renminbi/whatever at a pre-agreed exchange rate—the prevailing market exchange rate for the US dollar vs. ether/bitcoin/renminbi/whatever. In other words, you’re not touching the dollar at all, you’re just pricing other things in its exchange rate.

[6] One thing we obviously have not talked about here is central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which I’ve intentionally left out because that merits a whole separate discussion. However, it’s worth noting that CBDCs have the potential to change some of this trade-off, depending on how they’re designed (specifically whether or how much they’re remunerated).