Eurodollar Stablecoins, Bills, and Monetary-Fiscal Entanglement: Part III

Imagining a future monetary-fiscal arrangement

In Part I, we discussed the history of monetary-fiscal arrangements in the US. In Part II, we identified net new demand for Treasury bills from offshore dollar (Eurodollar) investors, mostly retail; and therefore, identified a potential path for the US to fund a larger share of its deficits with short-term securities financed by foreign retail investors. In Part III, we’ll take a look at how this state of the world might look.

DLT Eurodollars as fiscal relief valve?

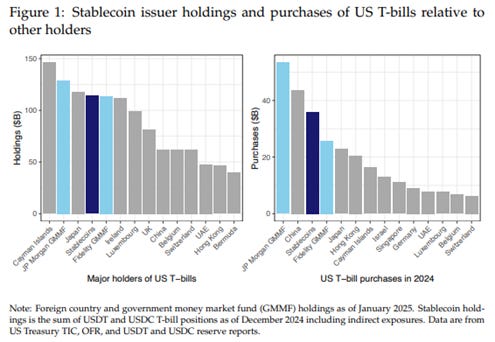

Stablecoin issuers are already one of the largest buyers of Treasury bills, larger even than the entire nation of Japan, per Ahmed and Aldasoro (2025):

Let’s imagine that our scenario from Part II happens: foreign retail investors measurably net expand demand for Treasury bills via stablecoin/tokenized MMF demand. Some thoughts/reactions:

Short-End Rates

This scenario seems straightforwardly to drag short-term rates down, albeit of course bounded by monetary policy. But the upshot is more demand for bills resulting in lower rates. A stylized finding from Ahmed and Aldasoro (2025) is that a two-standard deviation inflow into stablecoins lowers the three-month Treasury bill yield by 2–2.5 basis points over the course of ten days. As we’ve seen, State Street puts the pressure anywhere between 3 and nearly 9 basis points of T bill yield reduction in the longer term.

Of course, all prices are a balance between supply and demand—at some point, Treasury could increase supply enough to meet the demand, and we might end up back at our initial equilibrium, just with more T-bill stock. But all else equal, more demand and higher prices (lower yields).

Long-End Rates

If you don’t expect Eurodollar stablecoins to be inflationary (more on that below), then you might not expect long-end rates to rise in an expectations-theory-of-the-term-structure kind of way. You might however, think, “oh boy, that’s a lot of debt and its weighted average maturity is decreasing, and the people who are buying it are unsophisticated retail investors in Jamaica; this doesn’t feel great!” and read Reinhart and Rogoff and say, “I’d like a few more basis points of compensation.” That would be rational. In other words, taken with short-term rates, a steepening of the curve.

More mechanically, if the Treasury shifts issuance to the front end, they’d also be reducing supply at the long end. This could in turn have the effect of driving down long yields too.

Pressures will likely pull in different directions, and it’s a tricky general equilibrium question.

Debt Issuance

This is something we discussed in Part II: would potentially lower short-end rates tempt Treasury to issue more at the front end of the curve? My expectation is that Treasury would be tempted to. And they’d be somewhat justified in doing so, if the increased demand at the front end brings short rates down; in fact, one might argue that they’d have an obligation to shift issuance to achieve the lowest cost to the taxpayer, subject to the predictability limitation. One effect here, as State Street points out, is that this makes the overall economy less robust to cyclical fluctuations (i.e., more rollover risk to funding).

Of course, we don’t really have data for this, directly, yet. However, recent academic work from Barthélemy, Gardin, and Nguyen (collectively at the Banque de France and ECB) examining the interaction between stablecoins and commercial paper is at least suggestive. In their study, the authors find that “an increase in the demand for stablecoin tokens caused additional commercial paper (CP) issuance, when tokens were backed by CP.” This shouldn’t be any huge surprise, and the authors then make the natural speculation: “This novel connection may extend to other short-term funding markets, notably Treasury Bills, with effects shaped by issuer supply elasticity.” Right.

Inflation

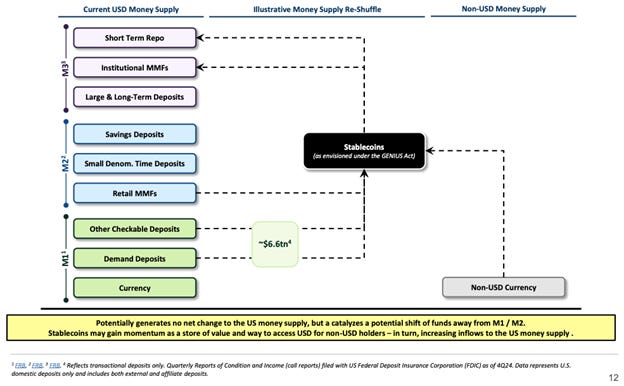

But that sort of looks and smells like monetizing the fiscal debt? Or at least monetizing more of it at the margin than is usual. Which begs the question: Would it be inflationary? This is a tricky question. In a world in which stablecoins exist only in an autarkic setting of the US, the expectation would be that they migrate money stock out of M1 and into M3, which might not by itself be particularly inflationary, assuming no new net money stock expansion. However, as we’ve seen, once you bring foreign currency into the mix, you’re net adding stock to the US money supply via the stablecoins. (This is all setting aside the interesting question of whether dollar stablecoins will themselves become a proper part of the US money supply in the future.) Per TBAC:

Of course, any inflationary pressure from Eurodollar stablecoins would be to some degree offset by expected dollar appreciation pressures, but the extent would depend greatly on numerous variables, of which a forecast I won’t attempt here. All to say (again): unclear, pressures will likely pull in different directions, and it’s a tricky general equilibrium question.1 But it doesn’t scream inflation, in and of itself, more so than how we’d think about normal bill issuance.

Financial Stability

There is a lot to be said about stablecoins and financial stability writ large (e.g., see here, here, and here). I’m not quite sure how to think about the effects of Eurodollar stablecoins specifically.

Start with the onshore spillbacks. On the one hand, one might think of less sophisticated foreign retail investors as being pretty “sticky” and less likely to run on stablecoins than sophisticated US fund managers; in this sense, they might be a shock absorber for US volatility. On the other hand, if and when they do run, research suggests that stablecoin Treasury buying and selling is asymmetric (more intense impacts when selling than when buying), and this can become a fire sale relatively quickly. And experience shows that electronic foreign retail depositors are the flightiest depositors of all; there’s a good chance stablecoin “deposit” flows would be more, not less, volatile in a state of the world where a large share of USD stablecoin circulation is in the Eurodollar market. That could spell more volatility in the front end of the curve, just as the Treasury sits on more rollover risk.

The effects on financial stability abroad seem less benign. One way to think about offshore retail stablecoin proliferation is that the average citizen can run out of their local currency a lot faster, which might be a shock amplifier. One could imagine a US-origin crisis in which, counterintuitively, purchases of stablecoins offshore help hold US short rates down as spreads widen, while amplifying bank runs and currency depreciation abroad (heard that story before?).

Monetary Policy Transmission

Here again, separating the aspects related to Eurodollar stablecoin issuance specifically (as opposed to stablecoin issuance writ large) is difficult, but the upshot relevant for monetary policy in any case is mainly the expanded base of stablecoins. For one, a shift into more money instruments being composed of stablecoins should reassert the now well-established dominance of the repo markets as prime monetary policy transmission markets. But it might materially impact the channels through which monetary policy functions. As Aldasoro and Ahmed put it:

Suppose the stablecoin sector grows 10-fold to $2 trillion by 2028 (as suggested by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee) and the variance of 5-day flows increases proportionally. Then, a 2-standard deviation flow would amount to roughly $11 billion, with an estimated impact of -6.28 to -7.85 bps on T-bill yields. These estimates suggest that a growing stablecoin sector may eventually suppress short-term yields to an extent that meaningfully influences the transmission of Fed monetary policy to market-based yields. (p. 20; notes omitted)

And it would also work in reverse: with a large stablecoin sector, monetary policy would influence the size of the asset class in ways that research suggests would be different to money market funds (at least for now, given that the main use case remains related to crypto, and given that stablecoins don’t—nominally at least—pay yield).

Fed Balance Sheet Changes

As stablecoins grow as a money-market instrument, the Fed’s balance sheet will likely change too, albeit variably depending on the extent to which the Fed supports this new money market. This is another category for which it’s difficult to segregate Eurodollar stablecoin demand from demand overall, but we’ve established that the former accounts for much of the latter, so we’ll proceed here regardless. For a comprehensive overview on the Fed’s balance sheet in response to stablecoins, see David Beckworth over at Macroeconomic Policy Nexus. I’ve lifted here a great paragraph from David that I think sums this up nicely:

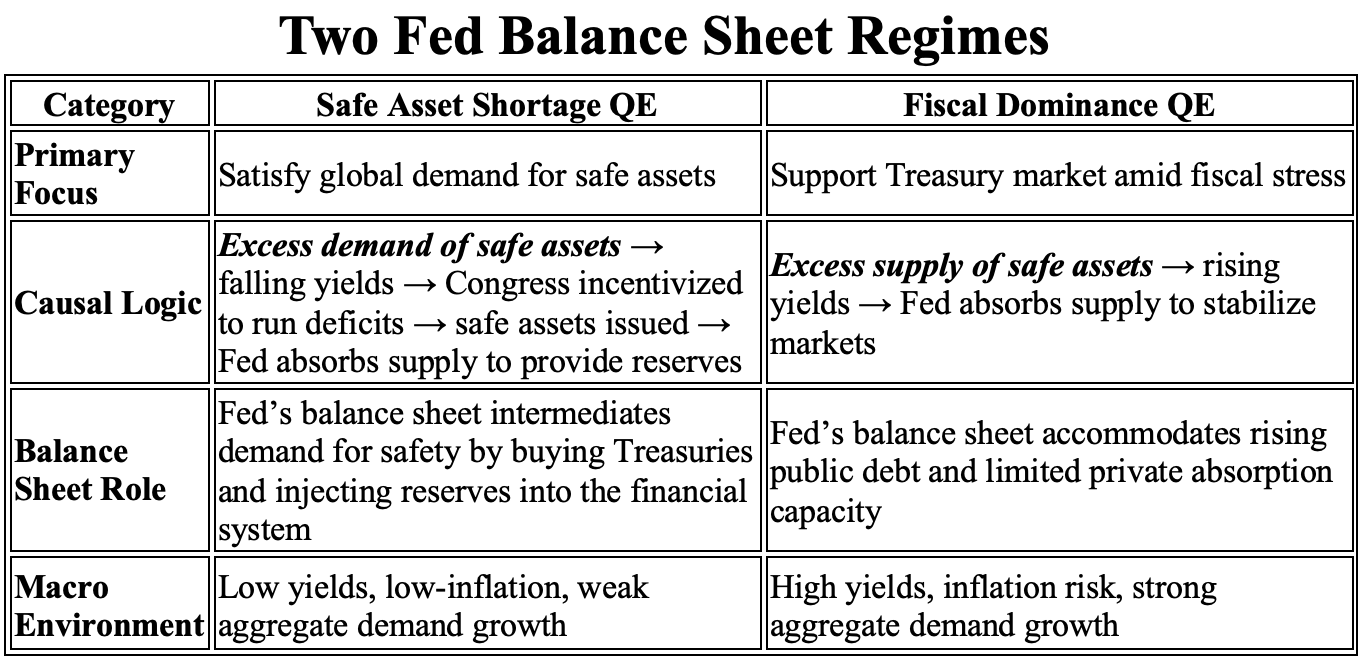

If stablecoins mean greater demand for Fed liabilities, then what kind of balance sheet expansion might this entail? In my view, there are two ways for understanding this process. One view—rooted in the “safe asset shortage” narrative—sees the Fed’s balance sheet expanding to meet an excess demand for safe and liquid assets, with quantitative easing (QE) functioning as a kind of public intermediation service that supplies the safety that private markets cannot. The other view—anchored in concerns about fiscal dominance—sees the Fed’s balance sheet growing in response to an excess supply of safe assets, as mounting public debt pressures the central bank to absorb and manage an expanding stock of treasuries. Stablecoins may intersect both of these dynamics: they could amplify global demand for dollar safety even as they deepen the channels through which the Fed intermediates the government’s swelling debt.

And an awesome table he’s put together for us:

Essentially, the QE story is that there is more demand for USD safe assets than there is supply (e.g., the Global Savings Glut) and the consolidated government (government + central bank) expand the supply of safe assets to meet that demand. This time, the Fed could expand its balance sheet (QE) via support for expanded stablecoin circulation rather than through conventional QE tools. It might do this by providing access—even if in limited “skinny master account” forms—to its financing facilities for stablecoins, and we could live in a world where the Fed’s liabilities include an ON RRP-style facility for stablecoin issuers.

The fiscal dominance story is that the Fed essentially finances fiscal deficits by supporting stablecoins, harking back to the WWII period we discussed in Part I of this essay series. In this universe, the outcome is the same—balance sheet expansion—but it’s the tail wagging the dog.

Of course, it can always be both! Here’s Beckworth again:

Stablecoins, in other words, may cause the Fed’s balance sheet to expand both to accommodate global demand for safe dollar assets and to simultaneously facilitate the absorption of ever-growing treasury issuance . . . Stablecoins, then, may become the bridge between the safe-asset-shortage and fiscal-dominance worlds: private instruments that generate public demand for Fed liabilities, even as they tether the central bank more closely to the Treasury’s balance sheet. The endgame may be a Fed balance sheet that is both structurally larger and more politically entangled—a central bank at the center of a digital safe-asset empire, but one increasingly constrained by the fiscal foundations that sustain it.

That first sentence pretty well encapsulates the thesis of this essay series: stablecoins represent two sides of the fiscal-monetary coin (pun very much intended).

Of course, regardless of fiscal dominance or stablecoin-QE, the composition of the Fed’s balance sheet might change as stablecoins replace other forms of money, as Beckworth lays out in another piece. For one, stablecoin displacement of cash2 could, all else equal, reduce the Fed’s seigniorage income, although a recent proposal for non-interest-bearing “skinny accounts” might limit the disruption. Similarly, there’s the chance that stablecoins eat away at (onshore) bank deposits (I think this is unlikely), in which case, in a world of skinny master accounts, Fed liabilities shift at the margin from banking system reserves to this new form of Fed liability, the skinny master account.

Where this all ends up is pretty speculative at this point, but these are possible worlds worth thinking through.

Dollarization

The scenario we’ve arrived at by way of Part II—expanding new dollar claims from Eurodollar stablecoins—seems unambiguously supportive of the dollar’s role abroad. The bridge between retail investors holding stablecoin Eurodollar liquidity in their crypto accounts or truly expanding offshore dollar usage will depend on other factors, like singleness of money, fungibility with demand deposits, and willingness of businesses offshore to accept them as means of payment. But the path to further incremental entrenchment of the dollar offshore seems clear, if not guaranteed. We’ve talked about this on this site.

KYC/AML/CFT/OFAC

The alphabet soup: sanctions and money laundering. We have talked about this here before, so I won’t spill too much ink on it now, but suffice it to say, I don’t have as pessimistic a view as some on the sanctions/money laundering/terrorism financing risks. Yes, to be sure, Tether & co. have a notorious past—there’s no doubt dollar stablecoins have been used by cross-border crime syndicates, thugs, autocrats, and drug-dealers. But that’s largely a failure of enforcement and compliance, not an inherent flaw of the technology, and the GENIUS Act should bring issuers that want to go legit into the regulatory fold by requiring compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act (see 12 U.S.C. §5903(A)). In fact, the programmability of smart tokens could, if leveraged properly, make them more secure than ledger-based money claims. Further, pseudonymity ≠ anonymity. As Darrell Duffie, Odunayo Olowookere, and Andreas Veneris point out in a recent IMF note, zero-knowledge proofs will allow KYC compliance while preserving users’ identities, showing that the choice between privacy and security is a false dichotomy.

Finally, recall that the US already has a virtually unregulated Wild West of offshore dollar use almost certainly supporting transnational crime groups: cash. Stablecoins aren’t a silver bullet—far from it—but they are leaps and bounds more traceable and enforceable than cash.

All told, while there’s much to worry about, I think we have reason to be cautiously optimistic here. And, as I like to say about policy choices in general, the benchmark matters: the alternative here is dollar cash or Bitcoin, depending on the use case, both of which are far dirtier and less regulated.

Abroad

Going hand-in-hand with dollarization is capital outflows from local currency into dollars, which would put depreciation pressure on local currencies and, all else equal, be inflationary abroad. In the classic Mundell-Fleming framework, these foreign jurisdictions (of which developing economies will be disproportionately affected) will be forced to hike rates or impose capital controls to limit FX slippage.

There will also be temptations to produce local competitors, either in the private (stablecoins) or public (central bank digital currency, CBDC) space. The Eurozone, for example, has taken the latter approach, as have numerous other jurisdictions. China even reacted to the GENIUS Act by publicly supporting a launch of its own renminbi stablecoin with the express goal of circulating offshore. (Although it seems this was quietly walked back.)

And then there’s the question of wealth effects. If the average family living in, e.g., Malaysia, now has a higher share of their financial assets denominated in dollars instead of ringgit, this naturally alters the wealth effects of foreign exchange rate changes. Rashad Ahmed has described this eloquently:

If households adopt significant amount[s] of dollar stablecoins, they have long dollar exposure on their balance sheet now, and they’re going to be exposed to currency mismatch on their balance sheet, and that’s going to be impacted by US monetary policy. If the Fed raises rates, you have dollar appreciation. That’s going to affect the value or the net worth of the household . . . Now, normally this would leave an amplified contractionary effect on the emerging market because they tend to hold a lot of dollar-denominated liabilities, but now they have quite a bit of dollar-denominated assets in the household sector. The value of that household balance sheet is going to go up, and that will hedge a little bit of the short dollar position of the public sector and the private sector.

Put another way, emerging markets tend to borrow—often via the official and private sectors—in dollars, with the household sector more muted, leaving the consolidated nation’s balance sheet short dollars. If households and companies acquire dollar stablecoins, though, this might actually have a balancing effect, where dollar appreciation has both wealth-creating and wealth-destroying effects simultaneously offshore. Food for thought.

Plus ça change

A view of American financial history shows that fiscal authorities have made clever use of channels through which to monetize fiscal debt if and when regular issuance becomes insufficient. In most cases, it takes a war, depression, or extreme disaster to push monetization to the edge. We’re very unlikely to see that kind of outright monetization with stablecoins, barring a crisis. However, we have shown thus far that:

most stablecoin ownership (stock) and transaction volume (flow) are offshore;

demand for stablecoins offshore continues to rise;

foreign retail investors are essentially the “final frontier” of untapped T-bill demand

This supposition—that the fiscal authority will be tempted to take advantage of this newfound ability to shift larger volumes of issuance to the front end of the curve as a result of burgeoning offshore stablecoin demand—does not rest narrowly on stablecoins. Tokenized MMFs or short-term bond ETFs would have similar effects.

So, what if you do?

New monetary-fiscal arrangements are neither “good” nor “bad” in reductive terms. A model in which stablecoins tap foreign retail demand for Treasury bills to some sounds like a weak form of fiscal dominance, while to others it sounds like the US provisioning a global public good. I lean toward the latter side of this debate, but of course both can be true at once. Such an arrangement would provide a global public good in constant demand: safe assets, which to foreign retail investors can serve as a better store of wealth and inflation shelter than local currencies. This particular manifestation of safe asset might also make remittances cheaper and simpler. In this sense, a stablecoin Eurodollar market would be a public good.

On the other hand, such an arrangement could result in more volatility in the front-end of the yield curve, pose financial stability risks, and increase foreign exchange volatility, while potentially having inflationary and/or distortionary effects in the US and exacerbating capital flow volatility abroad.

Stablecoin growth has the potential, like other monetary-fiscal arrangements in the past, to alter the structure of markets and to shift the way the government funds itself. There’s no guarantee that will happen, but we would be remiss to be guilty of a failure of imagination.

This series has benefitted from generous comments from Rashad Ahmed and Richard Berner, and from fruitful discussion and research-sharing with Elliot Hentov and Steve Englander. All mistakes and views are my own, but I want to thank these brilliant people for sharing their time.

This is also omitting any productivity effects, which I am struggling to think up deductively in any meaningful magnitude. If there was a material gain in productivity because of stablecoins, one might expect that to be disinflationary.

A pet peeve of mine though is the idea that stablecoins are completely revolutionary in reducing the use of cash. We’ve had digital payments for a very long time, and cash is mostly being “displaced” by other forms of digital payment. All to say, this is a totally plausible stablecoin outcome, but also certainly not limited to stablecoins.